Graphic memoirs for young adults have become a favorite sub-genre for me as both a reader and a teacher. Some of the most impactful titles I have brought to my college classrooms over the past decade are award-winning young adult graphic memoirs, such as Persepolis by Marjane Satripi, the March trilogy by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell; El Deafo by Cece Bell; and Stitches by David Small.

Graphic memoirs invite us into a person’s life story in multiple ways: we have to negotiate sequences between panels, words, and images, and we hunt for significance in an author’s life story through the visuals, the words, and their relationships. Memoir is always a product of authorial wrestling, as writers work to make a compelling narrative out of the hugeness and messiness of life. Graphic memoirists have even more at their disposal to accomplish that goal, and the images force us to see both the specificity of their unique experience as well as the larger contexts in which that experience might fit.

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, and Steven Scott. Illustrated by Harmony Becker.

One of the titles that most accomplishes that zooming in to a single person’s life experience and zooming out to societal contexts is George Takei’s graphic memoir, They Called Us Enemy. In this graphic memoir, Takei walks us through so much:

- his childhood in Los Angeles

- his family’s abrupt and traumatic forced removal to two Japanese internment camps

- his parents’ incredible job sustaining a childhood for their children while in the camps

- his emerging understanding of personal and societal prejudice

- his eventual recognition of the reality of internment and what his family and other Japanese Americans went through due to legalized discrimination

- his eventual career as an actor

- his lifelong advocacy for democracy and civil rights in the United States

Takei’s goals for readers are clear by the end--increasing people’s awareness of Japanese internment during WWII, and more broadly, helping readers see how their involvement in democracy is crucial. Takei put it this way in a PopCulture Network interview about the graphic memoir: “I hope the young people that read this book understand the importance of their being active participants in the process of our democracy. Our democracy is great, but it depends on us as a people to make the ideals of this country true.”

Compiling and Connecting

One of my favorite projects with Takei’s graphic memoir (or any graphic memoir) is to send students outside of the text to compile artistic artifacts that speak to the memoir in some way. Students can choose artifacts that capture Takei’s particular experiences; that speak to broader contexts, such as Japanese internment, the Civil Rights Movement, or LGBTQ rights; or that elaborate on a theme.

I ask students to choose 3 types of artifacts--a poem, a song, and visual art or visual document-- which they then represent and explain in a slide deck. Their slides include their artifacts, panels from the graphic memoir that connect to those artifacts, and written explanations of those connections.

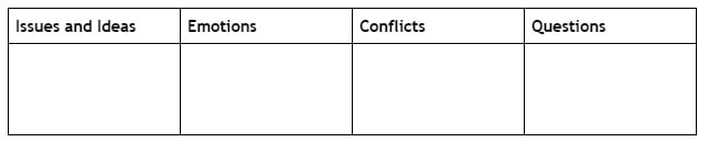

To help students get started, I ask them to brainstorm responses to the following categories.

What issues & ideas, emotions, conflicts, and questions matter to Takei in his memoir? What page numbers are most relevant to each category?

Then I give them directions for choosing their artifacts and explaining those choices:

For each element of the compilation:

Describe each piece of art or literature. Why did you choose it? It might be because it fits a specific moment in Takei’s life or it might be because it speaks to the larger issues he confronts.

Zoom in: Think of a moment or moments in Takei’s life when this piece of art would have been something he or others would have connected to . How does this piece of art fit those moments?

or

Zoom out: How does it relate to your graphic memoir as a whole? Which of the issues and ideas, emotions, conflicts, or questions that your memoirist experiences connect to this piece? Or what overarching societal reality does the piece reveal? What might Takei want us to consider about this reality?

Reference specifics from the piece of art (the poem, song, or visual art) and from the graphic memoir (please refer to specific pages and panels).

When I write about graphic novels, I often include pictures of specific panels as evidence for my ideas. You will want to do the same.

So what might show up in an artistic compilation for this memoir? Here are a few examples for each category.

Poems: Poems often push students to think thematically about the memoir or to consider powerful panels or moments of heightened emotion.

- “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes: The way the speaker teaches his instructor about his life experience as a Black man in segregated New York City speaks to the ways Takei teaches readers about Japanese internment and the dehumanizing losses it incurred. Students have also connected this poem to Takei’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, which played a pivotal role in his young adult life.

- “For a Father” by Elise Partridge: Upon her father’s early death, the speaker recounts key memories with her father. Takei’s father is one of the heroes of this memoir, which shows readers his father’s love, leadership, and teachings. Ultimately it is his father’s critical patriotism which seems to most inspire his own.

- “A House Called Tomorrow” by Alberto Rios. This poem celebrates how ancestors are always with you, even when “march[ing].” Takei depicts the ways his parents instilled in him a desire to protect democracy through participation. When he shows his own advocacy in the memoir, we see the connections to his father’s actions and words.

Songs: We talk about considering songs as one way to score the memoir: which songs might match panels in the memoir that are significant to you in some way?

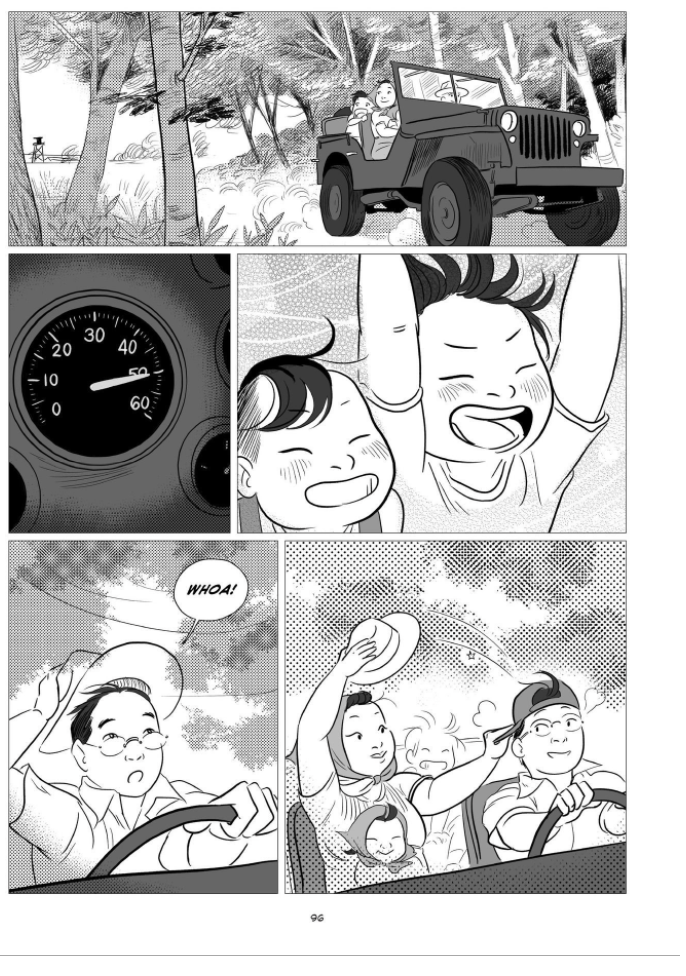

- “Riding in My Car” by Woody Guthrie: While living at Camp Rohwer in Arkansas, Takei features the day his family was allowed to drive off the camp site and visit a farm. This page is unique; it is one of the only moments when Takei’s family seems liberated, almost as if they were living their lives and enjoying a family trip together.It is not surprising that it was a treasured memory for Takei to represent and a stark juxtaposition with the reality of their lives.

- “Safe” by rapper Dumbfounded: Dumbfounded’s song “Safe” deals explicitly with a lack of positive Asian American representation in Hollywood, something Takei’s memoir addresses directly as he describes the beginning of his acting career. (Explicit lyrics.)

- Historical songs: After the attack on Pearl Harbor, popular songs featured anti-Japanese lyrics and encouraged violence. George confronts anti-Japanese racism throughout the memoir, including after the war when he returns to school in California. His teacher refers to him as a “little Jap boy” and continually makes him feel unwelcome. As he grows older, he cannot find any reference to the internment of Japanese Americans in the school’s history books, an absence that leads to his lifelong commitment to telling the story of his family and other Japanese Americans.

Art: Students go in different directions with this artifact, some connecting a piece of art to a moment of complex emotions and others looking for historical photography of the internment camps to elaborate on the settings of Takei’s memoir.

- Objeto rítmico no. 2 (segunda versão) by Mauricio Nogueira Lima, found in Google’s Arts and Culture site, is an endless swirl of black and yellow layered stripes. It captures a feeling of danger and being trapped: there is no way out of the pattern or the swirl. Connect this feeling to the emotions of Takei’s parents and other Japanese Americans when they were asked on government-issued mandatory questionnaires, labeled “loyalty questionnaires,” to serve in combat and to swear “unqualified allegiance” to the United States, all while being imprisoned because of their race and ethnicity (115). As Takei describes, they were caught in a circle -- to say yes was to admit that the questions were justified at all.

- Dorothea Lange’s Photographs of Japanese Internment Camps: This collection of photography captures Japanese Americans in California before internment (young children at school holding the American flag, for example), during the forced journey to leave California, and while trying to make a life in the internment camps. The photographs of so many different individuals build on the memoir’s representations of Takei’s day by day experiences of both injustice and community.

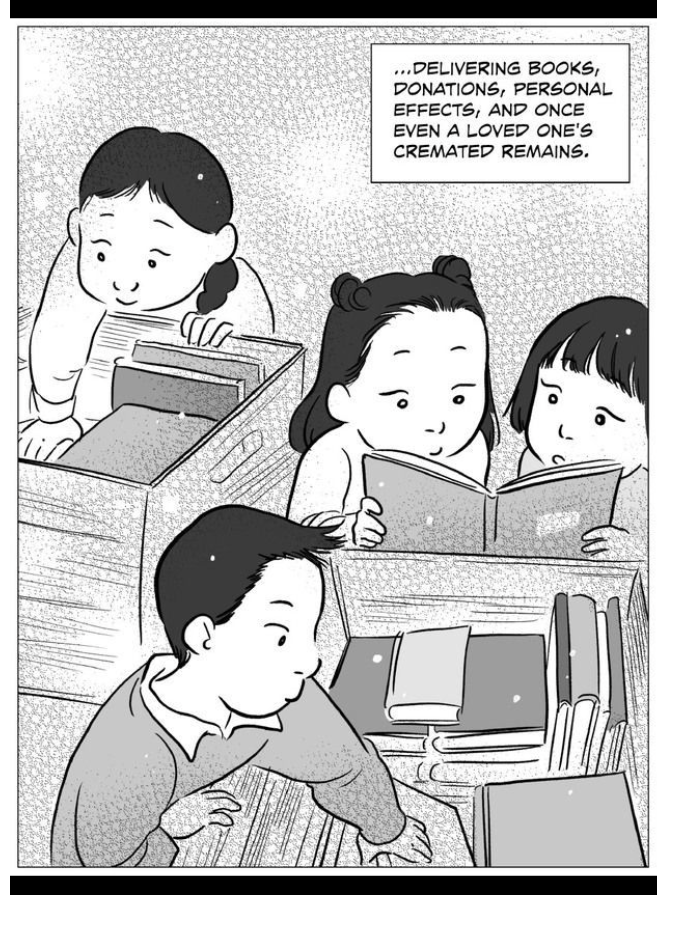

- Farmer Palmer’s Wagon Ride: In the art from this picture book by William Steig, we see Farmer Palmer driving items in his wagon, a picture that echoes one of the characters from Takei’s memory of internment. Herbert Nicholson, a Quaker missionary, brought books and goods to many Japanese American families in multiple internment camps, despite being violently and verbally assaulted on his way. Takei’s admiration for Herbert’s commitment and the moments of happiness his book deliveries provided are palpable.

Why We Need Graphic Memoirs

As I write this, Art Spiegelman’s memoir and narrative of his father’s survival in the Holocaust (Maus) is being pulled off of school library’s shelves. Takei’s memoir has already been challenged. Graphic memoirs ask readers to respond viscerally and imaginatively to real life; they take an issue of public significance and make it personal; and they ask us to see someone’s experiences. Instead of taking them out of our curricula, we need to find more ways to include them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed