Young people crave community and connection and often rely on their peer interactions to build and maintain their literacy practices. Whether it’s TikTok book hauls, YouTube book reviews, or Wattpad fan fiction, middle and high schoolers are interacting with reading and writing in shared spaces that are not only exploratory but creative and innovative.

Schools can tap into this kind of community building by hosting a “Whole School Read” in which every student, faculty, and staff member reads the same title at the same time and uses the book as a means to form connections and build understanding. In this post, I’ll outline some practices for this experience that have been successful in my own community!

Step 1: Finding Funding

Buying a book for every single student in your school or community will be expensive but there are ways to make this worthy investment. While every district or school has their own formulas and allotments for school budgets, here are a few ideas for finding financial support:

- Use Title I funding or other federal funding sources that your school is eligible to receive.

- Use funding from your school’s ancillary library budget.

- Partner with local bookstores or businesses to sponsor the event.

- Apply for grants that would cover or supplement the cost of the books.

- Utilize your school’s family organization for fundraising (PTO, PTA, PTSO).

- Ask families to provide their own copy of the text and cover the cost of students for whom the purchase is not accessible.

Step 2: Choosing You Community’s Text

There are a few factors to consider in choosing a text that will resonate with your community and push their thinking. Here are some that I’ve found to be the most important:

- What age or grade level will participate in reading the book? Your book should be accessible to your lowest grade or age but still be engaging for your oldest reader.

- What topics or themes is your community currently engaging with that they could explore through reading? Your book should open up conversation and build bridges while allowing space for all participants to share.

- How long will your community have to read this text? Think about your time constraints to assess the length of the text you choose.

Step 3: Planning Your Reading Progression

Once you have chosen and procured a text for your school community, you can begin the planning process of how you will encourage and incentivize your students, faculty, and staff to read and reflect on the text. Here are a few ways you can pace and structure your reading:

- Allot periods of independent reading over certain time periods during the school day to facilitate students reading on their own. This could be akin to “drop everything and read” time or a seminar class.

- Run the reading of your text through ELA, Intervention, or Personalized Learning Time classes where teachers can scaffold reading with styles of text engagement that are best fit for groups of students.

- Set a finish date or plan an end of text celebration and allow your community to read the text how they choose for themselves.

Step 4: Plan Your Text-Based Activities

When your community begins reading, you’ll want to decide how they will reflect on their text through writing, discussing, and creating. These activities will be dependent on the text you choose and the purpose behind your community’s selection, but here are a few general ideas:

- Mixed grade and faculty circles with guided questions to discuss the content of the book as well as themes that emerge.

- Create art projects grounded in the plot of the text or the concepts discussed.

- Journal prompts for each section or chapter of the text that the community can share.

- Host a literacy pep rally with events themed around the text and characters.

- Create a menu of activities ranging through modalities that students can create and then display in a community-based showcase.

- Invite the author to visit the school (virtually, in person, or create a short video for the students to view).

The undertaking of planning, implementing, and sharing the experience of a whole school read could seem a daunting task, but the benefits of a communal literacy experience will make all the logistical struggle totally worth it. The whole school read experience allows students to have conversations about important topics with their peers, their teachers, and their school community and engage with literate practice that encourages empathy and connection.

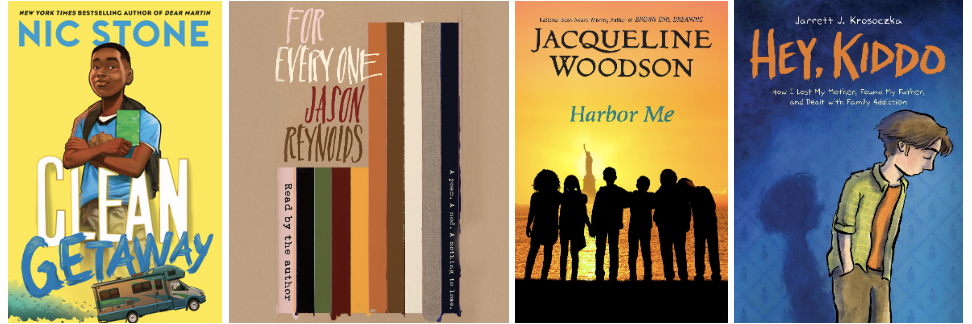

If you’re looking for a place to start with texts, here are four amazing middle grade and young adult texts that explore timely topics through ingenious prose, poetry, and graphics.

Anna Bernstein is a middle school educator and instructional coach, who has facilitated multiple "all-school-reads." You can connect with her on Twitter @MsB_MEd.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed