As English educators and English Language Arts teachers, we know that teaching is never apolitical. When educators and curriculum writers fail to include texts, voices, and identity representations in curricular materials, they are making political moves by omission. Yet, for preservice and in-service teachers, navigating the local sociopolitical contexts of public schools can be tenuous when those spaces deem the existence of marginalized sexual identities - either by law or de facto - as topics that are ‘controversial.’ It is important for English educators to demystify the idea of what is ‘controversial’ in ELA spaces and engage preservice teachers in sensemaking around the particular threshold concept that teaching is inherently political in order to include every student - at every identity marker - in coordinated efforts of literacy engagement.

What is deemed controversial is often localized, and these spaces are governed by local laws and ethoses that can often be at odds with the educators’ personal philosophies and lived identities. Disrupting the dehumanizing status quo in these spaces can require a lot of bravery, especially for a teacher new to the district or local schooling context (e.g., Rushek, Vlach, and Phan, 2023). Therefore, it is the teacher educator’s job to address this praxial at–odds-ness with their preservice teachers. This Monday Motivator blog post explains how three preservice ELA teachers in Kelli’s Literature and Other Media for Adolescents course went about tackling this at–odds-ness in the reading and teaching of young adult literature that features LGTBQ+ protagonists.

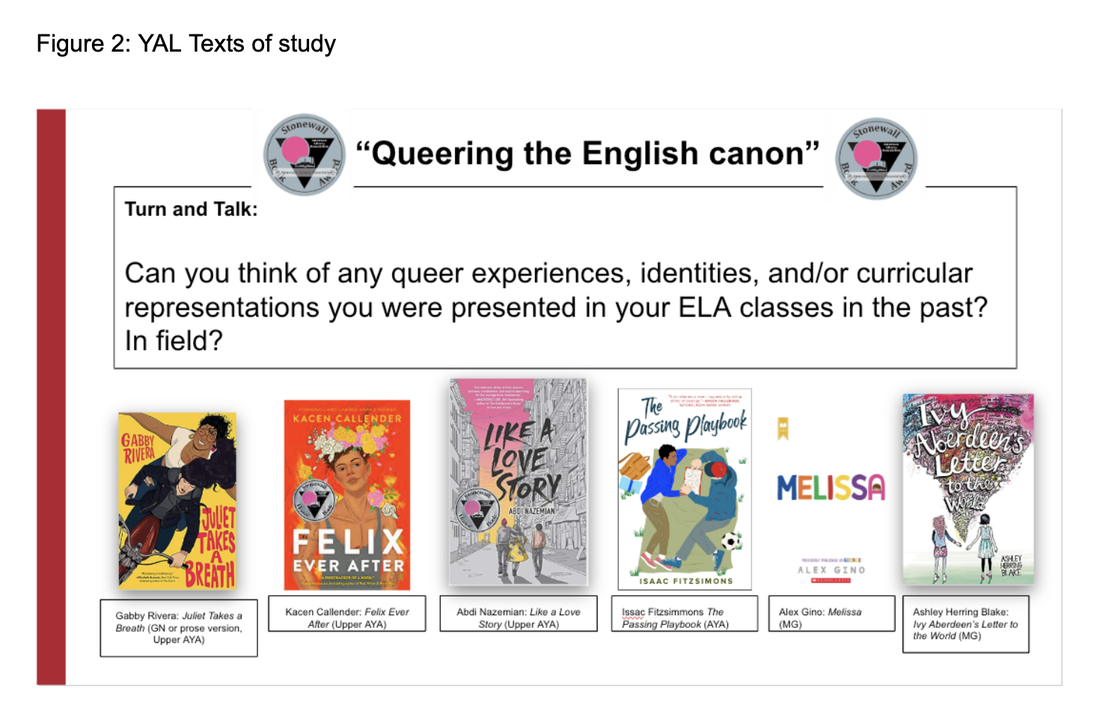

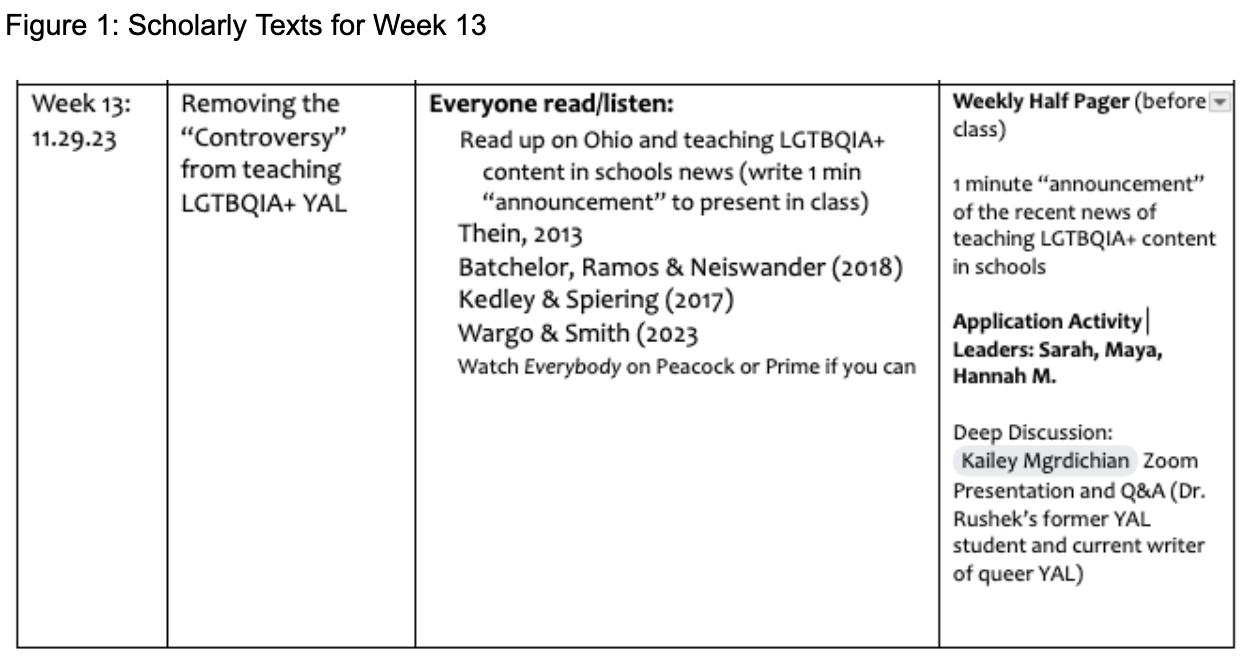

In Weeks 13 and 14 of the course, students are engaged in a module entitled “Removing the ‘Controversy’ from Teaching LGTBQIA+ Literature,” in which they engage with critical scholarship about the topic [see Figure 1]. In Week 14, students chose between six YAL texts that feature protagonists that identify as LGTBQ+. Choices for those preparing to teach secondary ELA were Kacen Callender’s (2020) Felix Ever After, Isaac Fitsimmons’ (2021) The Passing Playbook (set in rural Ohio, so of particular interest to the context of our teacher education program), Adbi Nazemian’s (2019) Like a Love Story, and Gabby Rivera’s (2016) Juliet Takes a Breath (either graphic novel or prose version). Choices for those preparing to teach middle grades ELA included Alex Gino’s (2015) Melissa and Ashley Herring Blake’s (2018) Ivy Aberdeen’s Letter to the World.

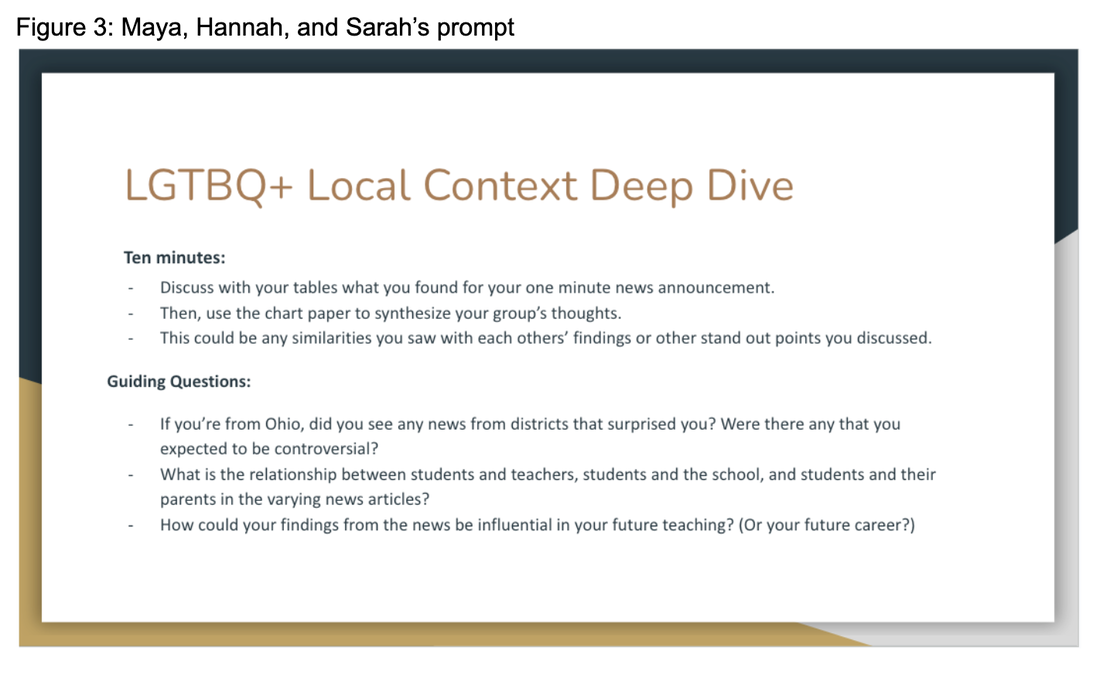

However, after this particular evening, we did not leave with this feeling, as Maya, Hannah, and Sarah engaged us in a multimodal (re)framing activity that left us feeling empowered and hopeful, even if for the duration of the class period. Inspired by the previous module (Representation in the Reimagination of Worlds: Who Gets to Be Fantastical?), in which the preservice teachers engaged with speculative fiction scholarship by Toliver (2020), Toliver and Miller (2019), and Worlds and Miller (2019) as well read from a list of young adult speculative fiction, the preservice teachers facilitating the lesson decided to apply their understandings of possibilities within speculative fiction to that of fiction featuring LGTBQ+ protagonists and issues. They asked us to create the front page of a newspaper that we wished to see in the media surrounding queer education [see Figures 4 & 5], and they gave us a model [Figure 7]. The class was immediately abuzz, collaboratively working in groups, ideas, chart paper, and markers flowing.

- “It’s a Great Day to be Gay! Local High School Students Stage Walkout to Oppose Anti-Queer Legislation”... “It was a beautiful thing to see,” says local conservative School Board member.

- “The Rural Ohio Times: Integrating LGBTQIA+ Curriculum Into English Classes Welcomed”

- “Local High School Board Unanimously Agrees to Add Gender-Inclusive Bathrooms in all Buildings”

- “Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath Chosen for School-Wide Book Club”

References:

Batchelor, K. E., Ramos, M., & Neiswander, S. (2018). Opening doors: Teaching LGBTQ-themed young adult literature for an inclusive curriculum. Clearing House, 91(1), 29–36.

Kedley, K. E., & Spiering, J. (2017). Using LGBTQ graphic novels to dispel myths about gender and sexuality in ELA classrooms. English Journal. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26359518

Rushek, K. A., Vlach, S. K., & Phan, T. (2023). Experiencing the cycles of love in teaching: The praxis of an early career Asian American ELA teacher. English Teaching Practice & Critique, 22(4), 546–564.

Thein, A. H. (2013). Language arts teachers’ resistance to teaching LGBT literature and issues. Language Arts, 90(3), 169–180.

Toliver, S. R. (2020). Can I get a witness? Speculative fiction as testimony and counterstory. Journal of Literacy Research: JLR, 52(4), 507–529.

Toliver, S. R., & Miller, K. (2019). (Re)writing reality. The English Journal, 108(3), 51–59.

Wargo, J. M., & Smith, K. P. (2023). Research: “So, you’re not homophobic, just racist and hate gay Muslims?”: Reading Queer Difference in Young Adult Literature with LGBTQIA+ Themes. English Education, 55(3), 155–180.

Worlds, M., & Miller, H. C. (2019). Miles Morales: Spider-Man and reimagining the canon for racial justice. English Journal, 108(4), 43–50.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed