In the YA edition of Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Professor of Botany at SUNY explores the intersection between indigenous knowledge of the natural world and Western scientific methods. Straddling the two approaches allows her to present a deeply personal and beautifully informed account of the complex interconnections within natural ecosystems, explained primarily through stories, made accessible to young readers in the new edition through illustrations and text boxes that provide supporting facts, definitions and opportunities for reflection. In particular, the chapter entitled The Council of the Pecans, demonstrates the interdisciplinary reach of this book through Kimmerer’s skill in weaving botanical information with historical events. By combining diverse strands such as the interrelationship between tree nut production and seed predators, the collective ability of trees to communicate with each other through pheromones and fungal networks, and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which ultimately placed her grandfather in a government-run boarding school, Kimmerer strives for a transformational “shared remembering” (p.10) that emphasizes gratitude, reciprocity and kinship among all living beings.

“[Home] a place where water binds two worlds; where coyotes confide in monsters; where hawks and

mockingbirds discern revelations from ancient trees; where my best friend basks in the sun beside me; and where…I search for the family I left behind.”

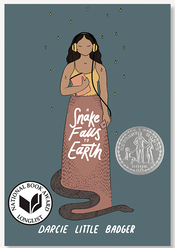

Stories like The Last Cuentista, and A Snake Falls to Earth express the dynamic nature of traditional stories: They adapt.

Ultimately, these texts inspire us to become what Kimmerer calls, “indigenous to place”, whether we are native or not, by cultivating our own metaphors and stories, specific to the places we inhabit. Doing so allows students to establish a creative dialogue with the local environment that moves from deep observation and classification to a unique evaluation developed through imaginative invention and, and eventually to an analysis of place that (hopefully) results in a protective appreciation of the ecological systems that support their homes and communities. Getting students outside of the classroom, exploring local places, is fundamental to this process and researching historical and contemporary land issues can add an interesting perspective. Finally, taking part in a habitat restoration project on the school campus allows students to transform their school into a supporting element within a greater ecosystem, while developing a unique language of place that makes them truly environmentally literate.

Regardless of whether or not the No Child Left Inside Act of 2023 is passed and enacted into law (I will remain cautiously optimistic!), environmental literacy is a crucial skill for today's students who will inherit the consequences of previous generations' ecological indifference. The good news is that integrating environmental literacy into our curriculum through connecting with stories, places and indigenous wisdom is a meaningful practice that guides students to develop a hopeful and sustainable relationship with the natural world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed