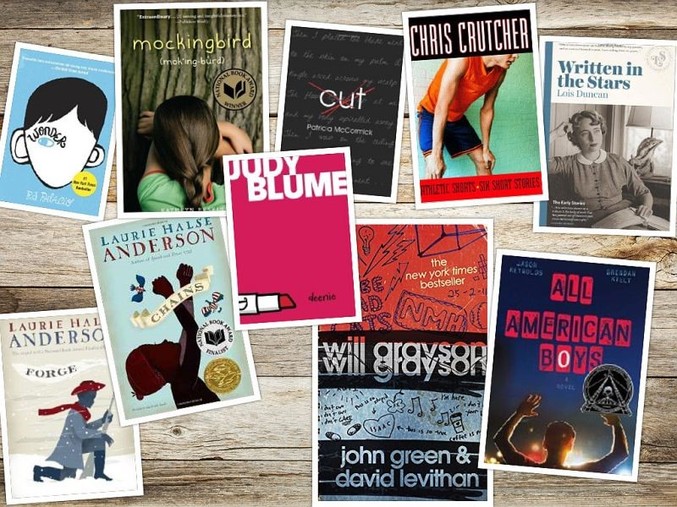

I have a storied history of not owning the right tool for the job at hand, yet I always manage to figure out a way to get the job done. No hammer? Use a big seashell. No decorative planter? There’s that shiny red soup pot I never use. No bookends? I could use two planters, gifted to me by my aunt. “Brinksmanship,” friends have said, clucking their tongues as I wield my “seashammer” with precision. I see my endless substitution as persistent resourcefulness, not recklessness. At present, those two planters sit behind me on top of my office bookcases. Between them is a long row of books “on deck.” These are texts I need to reread; books I may want to teach after reading them on those holiday reading benders; books that I will teach soon; and those that are germane to current research. But another way to describe this scene is to say that between the planters lies the most fulfilling aspect of the work I do as an English professor and teacher trainer: my YA. I may not always use the correct tool for less teacherly endeavors in my life, but I become more convinced with each passing year that advocating for YA by deploying it in learning spaces enables me to share the tool most apropos for the work my students have ahead of them. Age and content appropriate literature leads them and their students towards more sophisticated literacy. Said sophistication translates into lifelong learning and negotiation with ideas, both academic and civic. I sometimes reorganize this vital literature in purposeful ways for classroom use and share below a description of a new curricular strategy at work in my YA class.

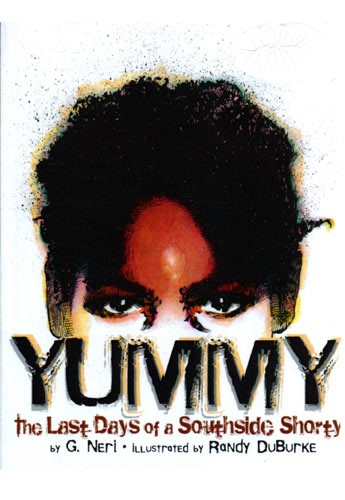

I found myself drawn to my student Shelby’s drawing of Yummy’s world. In her iteration, she wrote the word “AGENCY” in neat block letters. And, as if the circle in which Bil Keane drew his world reminded her not of the folksy comic strip but of a road sign, she drew a black, diagonal line across it, striking out the word she had so carefully written. This image manifested Robert Yummy Sandifer’s life. He had no agency when he accepted a gun as a present from a Black Disciple, saying that he’d never gotten a gift before. He had no agency when he used that gun in an attempt to make a name for himself in his gang of loving “brothers.” His parents, both in constant trouble with the law, also did not possess a great deal of agency, once we investigate their own troubled backgrounds. And Yummy’s grandmother, who took care of up to 20 grandchildren, also had little to no agency outside of her threadbare home. And without a path toward agency--that seemingly abstract “thing” granted to those with privilege and rarely earnable if you have no status--we will encounter another story like Yummy’s, Tamir’s, Trayvon’s, Bland’s, or even Shepherd’s, Clementi’s, or Hawkins’s. Stephanie’s structured activities began opening us up to our own assumptions and experiences as well as to the vast legacy of cultural trauma the produced one 11 year-old boy’s violence and anger. We thus populated the space between the bookends with ideas large and small, visceral and expository. Our reading of All American Boys will continue to inform our discussion of the same issues we found in Yummy. Though two decades separate the texts’ tales, the similarities between them and the tunekt cultural occurrences surrounding them demand our passionate attention.

If you are in the Las Vegas area, please consider joining us at our March 5th event described in the flier below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed