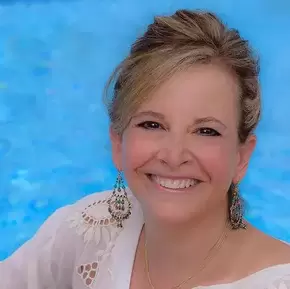

| Travis Reyes is a public-school teacher in Arlington with 22 years of experience. His students are amazing human spirits in 6th-12th grade at HB Woodlawn Secondary Program. He is certified in Spanish, ESOL, and Administration and Supervision; Travis uses all his skills to support learners in and out of the classroom. Part of teaching involves working with a group of students in a program known as a Teacher Advisor or TA. His students in the program have gone on to win Posse scholarships for college. He is currently a trustee at his Quaker meeting and serves on several educational and scholarship committees for Friends schools and the Baltimore Yearly Meeting. This summer, Travis will be presenting an LGBTQ book talk to young people at the Kennedy Center under the auspices of Fred Eychaner, a gay American businessman, and a prominent philanthropist. Travis is married to his husband Reggie, and they have three chihuahuas, Maní, Adobo, and Lumpia. |

― Benjamin Alire Sáenz, Aristotle and Dante Dive into the Waters of the World

| The Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network (GLSEN), an important organization recognized for supporting LGB rights for young people, shares that the experiences of LGBT youth are far from supportive. GLSEN shares that because of the lack of support, many LGBTQ youths tend to want to avoid school and skip school. In their climate survey, GLSEN mentions that “98% of LGBTQ students heard ‘gay’ in a negative way and that LGBTQ youth were nearly three times more likely than straight students to have missed school in the past month (44.1% vs. 16.4%).” While the data is revolutionary in describing the lives of LGBTQ youth and their experiences, the survey arguably can also be a case for inclusion and responsive instruction. This is because GLSEN also writes about how LGBTQ content is included within the schools and that this is potentially why LGBTQ youth struggle. GLSEN writes “…only 9.4% of LGB students are taught positive representations of LGB people, history, or events in their schools, and 17% had been taught negative content” (p. 8). What this means is that teachers need to consider focusing more on the damaging impacts of including only negative information and content on their learners who are LGBTQ. What this also means is that teachers can work on adding positive expressions of LGBTQ life and diverse ranges of experiences into the curriculum. GLSEN states that an inclusive curriculum takes down negative and anti-LGBTQ language and students are more inclined to feel safe. In fact, “[LGB youth] were less likely to hear ‘gay’ used in a negative way… (59.2% vs. 79.8%), they were less likely to hear homophobic remarks such as “fag” or “dyke” and, they were less likely to feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation (44.4% vs. 62.7%). |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed