1. Students should read a ton. They need to read a lot more that we have time for in a one semester class. If we are teaching classes full of future teachers we want them be able to make recommendations to all of the students that walk into their classrooms or tune in through some online tool. The more experience with adolescent literature our teachers and librarians have, the better served the students will be.

2. That should be exposed to as many genres as possible. This means that we should be be teaching some genres that we may not gravitate towards in our own reading. I don't read much fantasy, but I am grateful for the advice and recommendation I glean from Melanie Hundley, Stephanie Toliver, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and many others.

3. They should also be reading in a wide variety formats. I still hear some teachers are reluctant to teach graphic novels, books in verse, or the short story. Given the results of many award winners and award nominees over the last several years, we should be getting over this bias as soon as possible.

4. I think student should be aware of the the major awards, their histories, and the books that have made the short list in these awards.

5. There should be a large element of choice. I think this is especially true once students are introduced to the various major awards and aware of what is available in the various genres and categories middle grades, realistic fiction, scifi, fantasy, novels in verse, or memoirs.

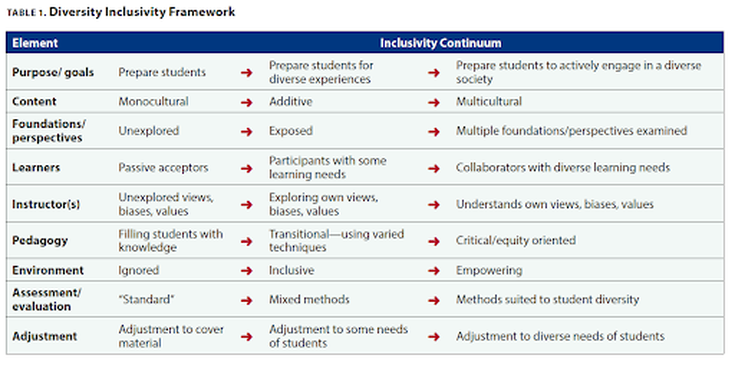

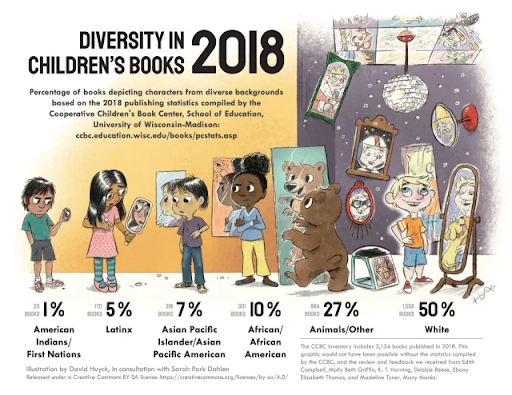

6. My last point for today's consideration is that the books should follow the guidance of Rudine Sims Bishop and provide our students, and by extension, their future students with windows, mirrors, and sliding doors. These remains true when the majority of the teaching force remains white middle class women and classrooms are rapidly becoming more diverse throughout the country.

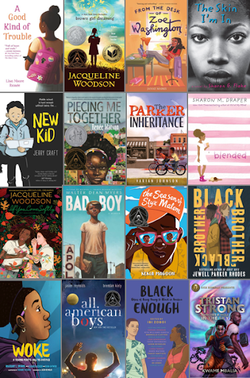

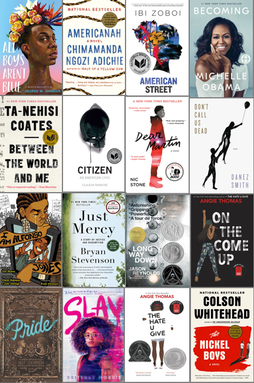

If I were to only teach books that matched my interest, I would be reading realistic fiction for older adolescents that focused on race, class, and gender. Given the current examples of political and racial unrest, I am selecting a lot of books that match my interests, but that also represent a variety of formats. I have a mix of a few established titles, but I am drifting to quite a few books that are relatively new. I have also included books representing many diverse peoples written by insiders from those communities.

Take a look. I would love to hear from you. I am sure that I share a few titles with many of you. At the same time, I know that I won't be teaching some of your favorites--or mine. I do think that we are in the midst of a fabulous influx of new authors. Yet, the fact remains that we have many well established authors who are still writing and producing wonderful works. (It is almost a physical pain that I am not teaching dig. by A.S. King or 100 Sideways Miles by Andrew Smith.) Every time I look at the list I can think of twenty authors or books that would fit in with what I am trying to do. Don't get me wrong, that is not a bad thing. In fact, quite the opposite, it speaks to an abundance of quality YA literature in the current moment. In fact, like many of you I enjoy a "to be read" list that is gigantic. So in fact, I am not complaining. I am relishing in a moment when it might be difficult to create a bad reading list if one is attuned to the current moment of YA literature.

The Books

With Very Brief Introductions

In no particular order except Holes will be first and Read Between the Lines will be last

Okay. I love this book and I am quite found of the movie. I can do without the way Disney imagine the lizards, but overall it does a good job. Starting with this book gives me a chance to talk about how the film industry has taken to YA literature at a lot of levels. I also like how this book is simultaneously about race, class, and gender in multiple ways. I have often argued that if I were teaching AP literature again, I would start with this book. I love the fractured narrative with intertwining narratives and elements of magical realism. I think if students can identify the literary elements in this text, they can tackle them in some of the books by some of the more traditional authors used in AP courses--Faulkner, Morrison, Dickens, Bronte and many others.

There is so much to love about this book and about Meg Medina. She has written wonderful children's literature and wonderful YA fiction. With Merci Suárez Changes Gears she has written what I consider a middle grades novel that garnered her the Newbery medal in 2019. This novel not only explores various aspect of Merci's coming of age story it also examines a multi-generational Cuban family.

Few YA novels have the staying power of Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. I can't even imagine how many editions have been published. It has been in print for 44 years and countless number of young black readers have been able to see themselves in the lives of Cassie and her family and friends. With this book they have a mirror and for many white children reading this book is their first experience with book as a window.

Every time I think about this novel, I hear my good friend and colleague, Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides forcefully, but politely telling me that American Born Chinese is a perfect book. If such a thing really exists, she might just be right. Certainly, for the history of the graphic novel and its consideration in the classroom and the literary canon this book needs to be mentioned in the same sentence with Maus by Art Spiegelman and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.

Craft's book was nominated for almost every award possible. I quick look at Craft's website demonstrates the list of accolades heaped on this 2020 Newbery winner. I love Craft's quote about his own work: "I make the kind of book I wish I had as a kid."

Woodson's memoir remains one of my favorite books of the last 20 years. It was one of those books that I knew I was going to write about as I read it. I was talking about it non stop even before it began winning award after award. Finally, I had a chance to write about it for First Opinions, Second Reactions. In my essay, I discuss how the book transported me back to my own childhood. Our experiences shape us.

Acevedo's stunning debut novel carries one of the most powerful and original voices in Young Adult literature. In addition, If your students listen to the audio version of this book, they will hear not only the power of Acevedo's words they will listen to the author herself read her work. Clearly, based on the reception of her next two books we have remarkable new talent in the world of YA literature.

Okay, I admit it, I am officially an old guy. The Vietnam War surrounded my adolescent years. I remember the news reports. I can still hear Walter Cronkite reading the news reports of battles in a far away place that became even closer as people we knew lost brothers and fathers in that conflict. As a young teacher I lived next an extended family of Vietnamese refugees. My children grew up and played with their children and grand children. This beautiful novel in verse captures the struggles of family trying to make their place in a new world.

I am late finishing this post. I have been on a long needed break. As a result, I am finishing this post as I listen to President Barack Obama pay tribute to John Lewis at his funeral at at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. Often YA Literature stands as a witness to historical acts of social justice. In our current moment, I can't imagine teaching a course on YA literature without using texts like this one that calls attention to moments of change. All acts are political. Without flinching I plan to teach a course that demonstrates how writers of YA fiction take on the issues of race, class, and gender. I can't do everything, but I can do this. I can "Get in good trouble, necessary trouble."

Nic Stone has become one of my favorite authors. I love the range of her style and her themes. For my money, Dear Martin stands as one of the lights on a hill as classrooms and communities talk about police violence. As your students fall in love with The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas or How it Went Down by Kekla Magoon or Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes remind them of this wonderful book.

This book is a remarkable example of collaboration. While I love the story, the characters, and the craftsmanship, I am enthralled with the work accomplished by the combined work of Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. I believe that our issues will find a resolution more quickly if we can work together to discuss hard and uncomfortable situations. Jason and Brendan model that work for us.

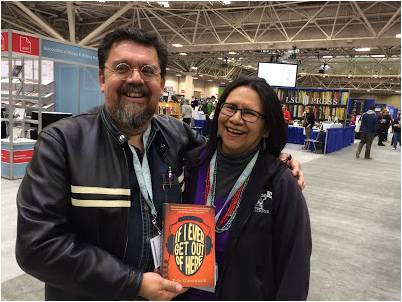

I had the great privilege of meeting both Gilly and Kim at a dinner as part of my activities at the 2019 NCTE convention. I didn't know the book, but I knew I had found another model of collaboration. Kim and Gilly work together to tell the tough stories that ask the tough questions and explore the potential answers that will move us forward. Read this book! Then, find a way to collaborate with someone in order to answer the difficult questions that surround you. Let's find a way to take a step forward. I immediately began to scheme so that they could speak at the 2020 UNLV Summit. What a gift.

I spend time finding books that represent own voice writers who are writing novels that represent under represented, diverse communities. I was invited to a dinner in Las Vegas with Laurie Halse Anderson about a 18 months ago and she was carrying a book. I asked her what she was reading and she began carrying on about the Patron Saints of Nothing. I have learned to pay attention to Laurie's recommendations. And, since I am putting her novel, The Impossible Knife of Memory, reluctantly to the side this year it is only fitting that I include this fine novel. It didn't take me long to be a fan and Randy Ribay was on my short list to be a keynote speaker at the 2019 ALAN workshop. Thankfully, he was being promoted by his publisher, so that was a quick conversation. His keynote speech is available at this link on his webpage.

I love the cover of this book. The word Resist written across the hat could be the subtitle for this book. As I read it I felt that it could be written as a direct response to incarcerated children and families on the southern border of our county. Of course it wasn't. Books take a while to get from the authors imagination to the page, through the editing process, and into the hands of readers. Ahmed does a remarkable job envisioning a situation of governmental abuse and the fear of the "other" that seems all to prevalent in our society today.

Dystopian, apocalyptic, and futuristic fantasy that wonders what might become of us if we continue to push each other into silos that prohibit us from moving forward. This book quickly reminded me in tone of McCarthy's The Road, of Huxley's Brave New World, Golding's Lord of the Flies and in some interesting ways it becomes a journey novel that questions Twain's Huck Finn as an alternate tale of the difficulty of finding what has been promised. Cherie Dimaline is a member of the Georgian Bay Metis Community in Ontario. While the book can easily be defined as Canadian, this indigenous author reminds us how artificial the boundaries that are drawn in the new world really are. They were drawn across traditional tribal lands with little regard for the people who were already there.

One of my favorite topics to examine in YA literature is the role of music in a book. Eric Gansworth's passionate narrative of a Tuscarora youth finding his way through adolescences is punctuated by the music of 1975. This period piece can not only be read, but students can enhance their experience by listening to the music that inspires and contextualizes Shoe's experiences.

This book by Victor Martinez was the first book to win the National Book Award in 1996. This is a perfect example of a book that shouldn't be ignored just because it is old. The power of this own voices narrative deserves a moment of revitalization.

I have been a fan of Maria Padian's work for quite awhile. Trevor Ingerson sent me a few books and Maria Padian's Wrecked had a little post it note that suggested this book might suit my interests. Well, Trevor was right. Now with her newest novel, How to Build a Heart, Padian demonstrates that she is a moving force in YA fiction. I look forward to discussing this book with my students. Izzy Crawford misses her father who died Iraq. For six years Izzy and her mother have lived with relatively little support from her mother's family in Puerto Rico and her father relatives in North Carolina. Can this mixed race girl find a place to belong?

Oshiro's debut novel took me completely by surprise. I loved how this story of both grief and action built around some of the issues that are at the center of current protests throughout America's cities. I kept wondering why I hadn't heard about this book sooner. I am anxious to see what comes next.

I love this book! It was one of the books that I think deserves another opportunity to be re-promoted. When I first read it I thought "This book is going to be on everyone's list!" While that didn't happen, what did happen is that Jo Knowles is

on everyone's list. I don't know any one who has read one of her books who is not taken by her themes, characters, and style. Last year at the 2019 ALAN Workshop she demonstrated her commitment to kindness. Unfailingly her books demonstrate the power of fiction to inspire hope. At UNLV, we look forward to hosting Jo as one of the keynote speakers at the 2021 Summit on the Teaching and Research of Young Adult Literature.

What are you going to offer your students. I would love to know.

Until next week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed