Before I pass you over to Susan and her daughter, I recommend you visit the previous post she contributed to Dr. Bickmore's YA Wednesday.

Through my Daughter’s Eyes: Lessons Learned from YA Lit

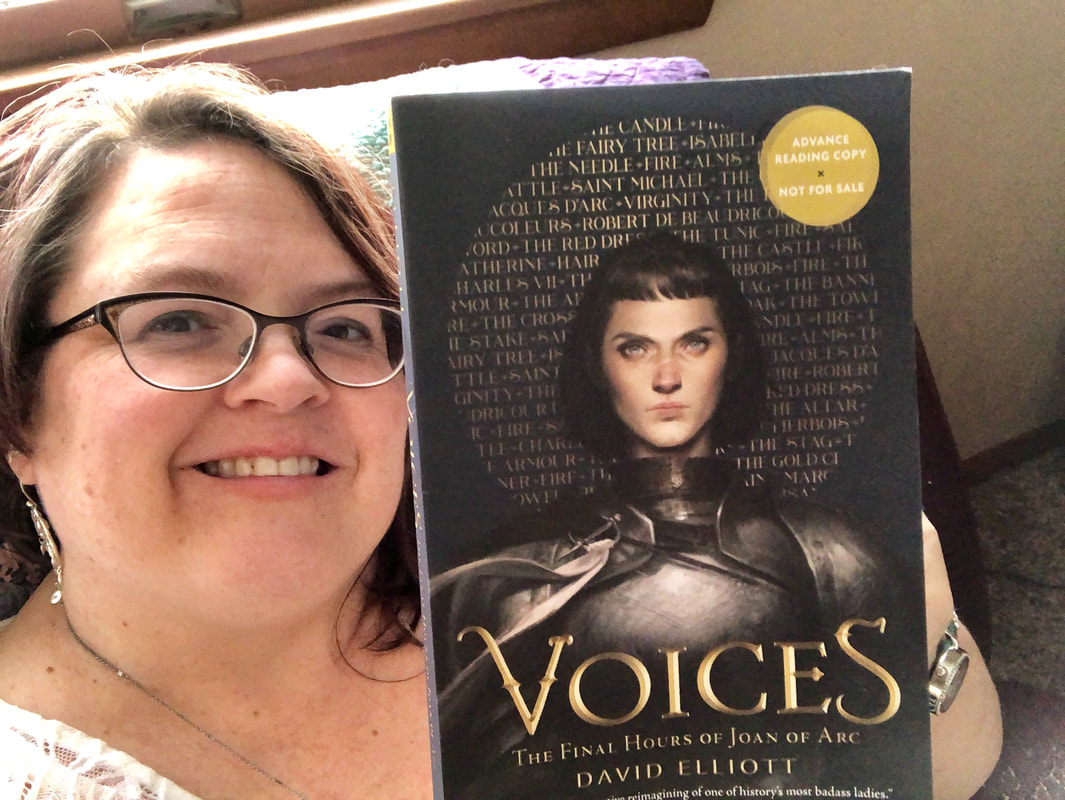

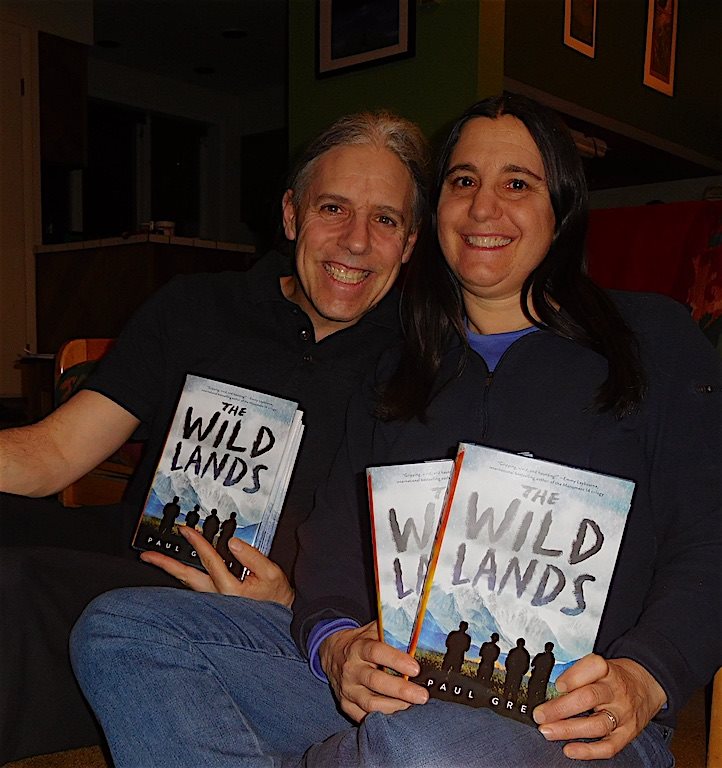

Dr. Susan Densmore-James, a.k.a. The Book Dealer

Elena, a.k.a The Junior Book Dealer

What I do know is this: these trips allow me to reflect, and weighing heavily on my mind are several things.

1. The amount of blame I see daily related to our current national climate and specifically the blame placed on YA lit. as an alleged factor of our young people’s problems

2. How YA Lit is really impacting our youth, and

3. How this is affecting MY youth, in particular.

I am a single parent to a wonderful (and moody) teenage girl whom I adopted from Russia. The past year has been challenging, to say the least, and with a stressful job and aging parents who are often hospitalized added to the mix, the airplane trip I just completed was the first big block of time to grapple with some of the issues I am contemplating related to YAL, society, and parenting, in particular.

| As a researcher and lover of knowledge, the first impulse was to read every piece of research I could find. After near-memorization of “Attack of the Teenage Brain” (Medina, 2018) and books on bibliotherapy, I realized there are a huge number of researchers who, in many respects, can speak to the adolescents’ needs way better than I. In fact, every time I write an article, my first reaction is panic; I label myself unworthy, so I feel the need to read every publication related to the topic. I spent many hours down “the rabbit hole” reading further research on bibliotherapy, adolescence, and the value of YA lit. What did I realize? Well, a lot, but first off, I am an expert. An educator of 29 years (teaching middle and high schoolers for 17 of those), my student-given nickname of The Book Dealer based on my ability to match readers with text, and now a mom to my own teen are not weak credentials. |

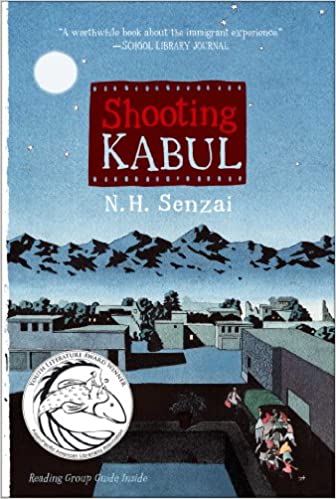

This past summer, my community of YAL was attacked, and specifically Crutcher’s book, Loser’s Bracket, as the author of the article selected a partial passage from the book to give evidence as to the “unbearable” darkness of young adult literature. Mr. Salerno made, as my 9th grade daughter calls it, a “big statement” in saying the lists of recommended titles by the curators of YA literature “evidently” assume that all students arrive to school traumatized in some way. (The Community responded to the article and you can read it here.) From past experience with Crutcher’s books (which were, by the way, always the top favorites of my students), I always finished his books feeling uplifted. There are always adults who are champions for kids and young characters that persevere, despite being not dealt the best hands in life. I wanted Elena’s honest opinion of Crutcher’s book and Salerno’s article.

Loser’s Bracket is the first book Crutcher has written that is told by a female character’s perspective, so I fought to get my hands on an ARC (fought because teens and adults alike want to read his work). After my daughter and I finished reading it, she wanted to be the one to write the book review (this is a good sign), as she is “The Junior Book Dealer” on my blog site. I included the review in its entirety, including her notes to teachers, as well as the concepts/themes she thought could be used for teaching this book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed