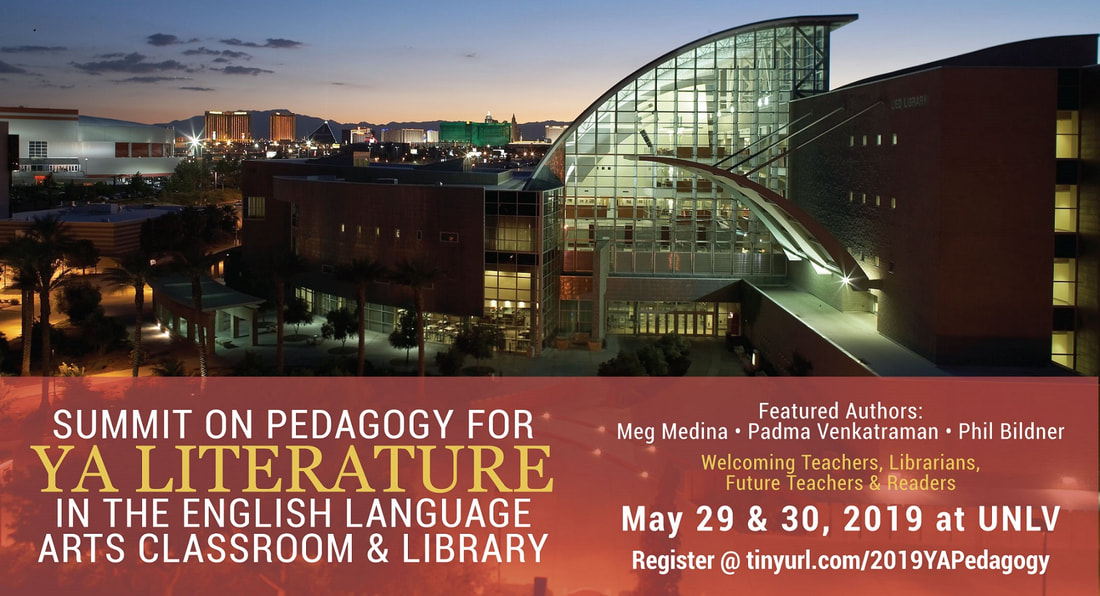

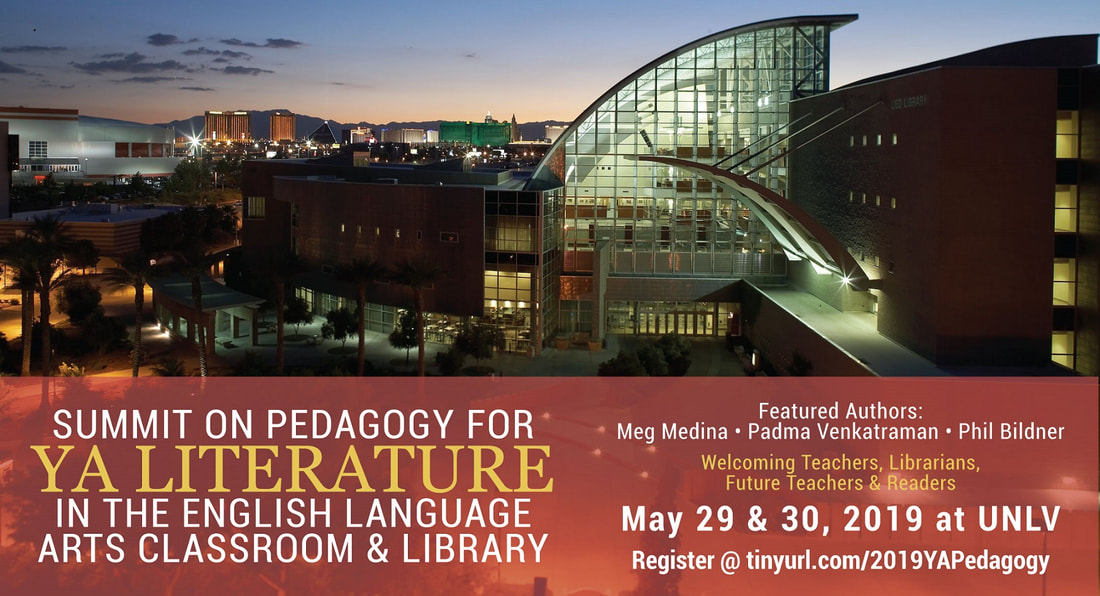

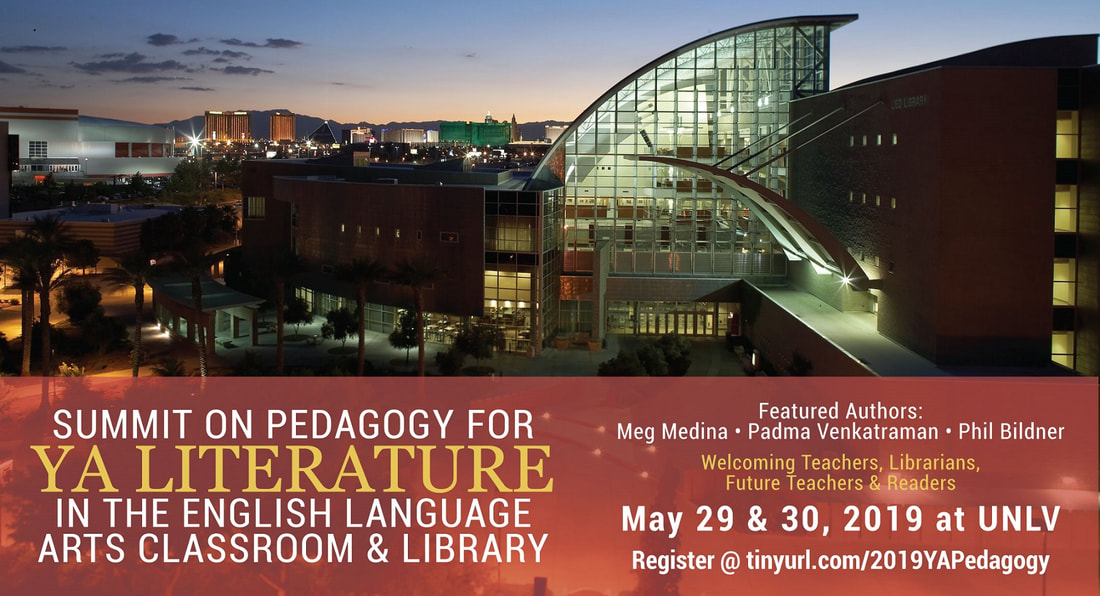

Another fun connection is that she and Kia Richmond met at the summit. Kia is also a contributor to the blog and has a book on YA and mental illness. They became fast friends. You can find Kia's post here. Professional learning is often just as much about friendships and connections as it is collecting materials to use in the next class.

Thanks Diane, for contributing once again.

May, Mental Health Month, and a Musical: Dear Evan Hansen

#curestigma #iamstigmafree #WhyCare

Recently, I was able to bring together two interests of mine, one new and one longstanding. I’ve recently become more acquainted with musical theater, and I have spent years reading YA literature of mental illness; so, imagine my excitement when I realized that both of these subjects come together Dear Evan Hansen!

When my colleagues and I at Moorpark College began teaching Hamilton a couple of years ago, a particularly avid theater fan in the class told me about Dear Evan Hansen. I knew I wanted to explore the musical theater genre further, so I immediately ordered the book and the soundtrack, and then I saw one of the Hollywood Pantages Theater performances in November of 2018. With its focus on teens, social media, and mental illness, I knew the play would be a great selection for my introduction to literature class at the community college where I teach. I usually theme this class as a young adult literature class, but sometimes I struggle to find plays because there is not a large body of YA drama--YA literature, after all, almost always means YA novels.

Indeed, the play Dear Evan Hansen has recently been adapted into a young adult novel. While my class studied the play, and my references will be to the text of the play, both versions are great ways to get teens talking about mental health. From Evan Hansen’s suicide attempt to Connor Murphy’s completed suicide, and from Evan’s social anxiety to Connor’s drug addiction, the text can inspire many conversations about mental illness and wellness.

As Kia Jane Richmond has argued right here in YA Wednesday as well as in The Language Arts Journal of Michigan and The ALAN Review, the language we use when we talk about mental illness can be used to challenge or reinforce the stigma that exists in our society today about mental illness. Dear Evan Hansen provides us and our students with many fruitful opportunities to examine the language that characters use to talk about mental illness and the consequences of that language use.

Not just Connor’s classmates but also Connor himself uses derisive language to refer to mental illness. In Scene 2, Evan and Connor have an encounter that will drive the rest of the plot. Evan has written one of his therapeutic letters to himself. Connor finds it while both boys are in the computer lab. When Connor finds Evan’s letter, in which Evan has mentioned his hopes for developing a relationship with Zoe, Connor accuses Evan of composing the letter just to make Connor “freak out” so that Evan can “tell everyone [he’s] crazy, right?” (1.2). Earlier in the scene, Connor had mockingly signed Evan’s cast (his arm is broken from a fall from a tree), saying, “Now we can both pretend that we have friends” (1.2). Both remarks show that Connor is aware of his marginal status among students and clearly hurt by it. Certainly, language and labels have stigmatized Connor, who ends the scene by absconding with Evan’s letter.

In a helpful article in the Huffington Post, one psychology professor explains, “Using a judgmental or degrading language prevents us from recognizing mental health problems, seeking help and providing help” (Debiec qtd. in Holmes, 2019). Experts contend that “Simply put, ‘committed suicide’ conveys shame and wrongdoing; it doesn’t capture the pathology of the condition that ultimately led to a death. It implies that the person who died was a perpetrator rather than a victim” (Holmes, 2019). Nine out of ten suicides are the result of an underlying mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

The experts call on us to treat deaths due to mental illness with the same respect as those that occur due to physical illness and not suggest that victims of mental illness were in full control of their behavior. To illustrate how the brain of a severely mentally ill person is not functioning in the same way a normal brain that could be held accountable for “committing” an act, I like to show students the Mayo Clinic’s brain scan of the depressed versus non-depressed brain. Thus, the phrase Connor’s dad uses in the play, “Connor took his own life” (1.4), and the phrase Evan uses, “killed himself” (2.7), are just as objectionable as “committed suicide” because they place the sole responsibility for the death on Connor rather than on the mental illness.

Medication noncompliance is very risky, but Heidi’s response, though it includes some surprise and a couple of questions, is “Well, great. That’s great. It’s...I’m proud of you” (2.2). Her response suggests that not needing medication is something to be proud of. This belief contributes to a social atmosphere of shame for those that need medication. It also suggests that Heidi is uncomfortable talking about mental illness with Evan and would rather end the conversation than pursue it. It is not until the end of the musical that Heidi and Evan realize how much their refusal to discuss mental illness at all has hurt their relationship. So, while for much of the play Heidi is supportive on the surface and doesn’t use unkind words when she discusses mental illness, her refusal to talk much about it, coupled with Evan’s refusal to talk about the subject, show the danger of the absence of language to discuss mental illness. So, while in some parts of Dear Evan Hansen, hurtful name-calling is used to discuss mental illness, in other situations, there are simply no words at all.

Underlying both of these conversations is the fact that Evan is actually hiding his suicide attempt by telling people he fell out of a tree. The stigma of suicide is so great that Evan is afraid of what his own mother would think of him if she knew the truth: “You’ll hate me…You should. If you knew what I tried to do. If you knew who I am, how…broken I am” (2.9). This is not the first time Evan has used the metaphor of “brokenness” to describe mental illness. His broken arm and cast provide the iconic image for most of the musical’s publicity materials, and the message of the first act finale song is, “And when you’re broken on the ground / You will be found” (1.12, “You Will Be Found”). In an angry outburst at his mother, Evan demonstrates his internalization of the social stigma against people with mental illness: “They [the Murphy family] don’t think that I’m, that there’s something wrong with me, that I need to be fixed, like you do…I have to go to therapy, I have to take drugs” (2.7). The implication is, of course, that needing therapy and medication is shameful.

In closing, I’d like to look at the Murphy family’s use of language to describe Connor’s addiction, illness, and suicide. Since Connor’s emotional dysregulation began in childhood, it is not unreasonable to assume that an underlying mental illness accompanies his drug addiction (which remains unspecified throughout the play), even though addiction disorder, in and of itself, constitutes a mental illness (see K. J. Richmond’s Mental Illness in Young Adult Literature). Often, alcohol or drug addiction co-occurs with another mental illness.

The National Institute of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) tells us, “Multiple national population surveys have found that about half of those who experience a mental illness during their lives will also experience a substance use disorder and vice versa.” Studies have also found that “over 60 percent of adolescents in community-based substance use disorder treatment programs also meet diagnostic criteria for another mental illness” (NIDA). One explanation for this co-occurrence or dual diagnosis is that people suffering from mental illness may attempt to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs.

In it, she asks,

“Why / Should I play the grieving girl and lie? / … I will sing no requiem / Tonight / … After all you put me through / Don’t say it wasn’t true / That you were not the monster / That I knew” (1.9).

In addition to calling Connor a “monster,” in her song, Zoe also compares Connor to a fairy-tale “villain.” At this point it might be helpful to discuss with students that, while we may not agree with Zoe’s name-calling, she has a right to her feelings of terror and anger. After all, addiction and mental illness don’t just affect the sufferer but also his/her loved ones as well. Certainly, Connor’s behavior was troubling; Zoe tells us that it included “trying to punch through [her] door, screaming at the top of his lungs that he’s going to kill [her] for no reason” (1.9). We should remind students that point of view is important when discussing stories of mental illness and that each person’s perspective is different and valid.

Larry and Cynthia criticize each other’s approaches. Cynthia uses phrases with negative connotations, such as “Do nothing” and “Wait and see,” to describe Larry’s response to Connor’s struggles (2.9). Larry describes his own approach in a positive light, as one rooted in an ethic of hard work. While this gives the viewer/reader/listener a more sympathetic view of Larry, his sentiments suggest the popular misconception that hard work alone can conquer mental illness. In his song, “To Break in a Glove,” which is ostensibly about more than baseball, he uses phrases and words like “stick it out,” “it’s the hard way, / but it’s the right way,” “commitment,” “grit,” and “follow through” (2.3). Cynthia also bitterly recalls Larry’s response to Connor’s first threat of suicide: “He just wants attention” (1.9).

This phrase is a common, but dangerous cliché. Students should be advised to take any threat of suicide seriously. Larry, in turn, accuses Cynthia of “lurching from one miracle cure to the next” (1.9). At this point, students could explore the difference between the concepts of “recovery” and “cure.” Most mental health advocates and addiction experts remind us that while “cure” is impossible, “recovery” is absolutely possible. While a mental illness or predisposition to addiction will never go away, it is possible to manage these conditions and lead a meaningful life. (For a detailed discussion of YA novels that emphasize the road to recovery, please see my article about disability narrative theory and mental illness fiction.) Fortunately, this is a lesson that Evan finally begins to perceive at the end of the musical: “Dear Evan Hansen: / Today is going to be a good day and here’s why. Because today, no matter what else, today at least…you’re you. No hiding, no lying. Just…you. And that’s…that’s enough” (1.9).

References and Recommended Resources

Holmes, Lindsay. (27 Mar. 2019). “Why you should stop saying ‘committed suicide.’” Huffington Post.

Levenson, Steven. (2017). Dear Evan Hansen. Music and Lyrics by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul. New York, NY: Theater Communications Group.

Mayo Clinic. (1998-2019). “PET scan of the brain for depression.”

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (21 Sept. 2016). “Mental health facts: Children and teens.”

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (n.d.). “Mental health facts in America.”

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2019). “Why care?”

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2019). “Infographics and fact sheets.”

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (Feb. 2018). “Common comorbidities with substance abuse disorders.” National Institute of Health.

Richmond, K. J. (23 Aug. 2017). “Language and symptoms of mental illness in young adult literature.” Dr. Bickmore’s YA Wednesday.

Richmond, K. J. (2018). Mental illness in young adult literature: Exploring real struggles through fictional characters. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio/Libraries Unlimited.

Richmond, K. J. (Fall 2018). “An examination of mental illness, stigma, and language in My Friend Dahmer.” The ALAN Review 46 (1), 42-53.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed