| Dr. Becki Maldonado is a ninth-grade English teacher at Parkside High School in Salisbury, MD. She is a committee member of the Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. Her scholarship and research focus on arts integration, nonfiction text, text selection, and developing and exercising teachers’ critical consciousness, along with the use of critical dialogue to develop social awareness in education and the community. She is also the editor of Arts Integration and Young Adult Literature: Enhancing Academic Skills and Student Voice. |

In 1658, John Amos Comenius, a Czech educator and social reformist, wrote the first children’s textbook with pictures – Orbis Sensualism Pictus, “The Visible World in Picture.” Having lived under the oppression of the German feudal lords, Comenius believed “all the knowledge and all the scientific achievements belong to all people and all nations, and that everybody should be enabled to get to know them, and in this way, by possessing knowledge, have the power” (Lukaš & Munjiza, 2014, p. 34). From this belief he advocated for children, holding fast to the understanding that students “were born with a natural craving for knowledge and goodness, and that schools beat it out of them” (Moravian University, n.d.). While his pedagogical influence grew in Europe, his influence did not span over the Atlantic Ocean until the early 20th century when Orbis Pictus and the Great Didactes hit the shore of the United States.

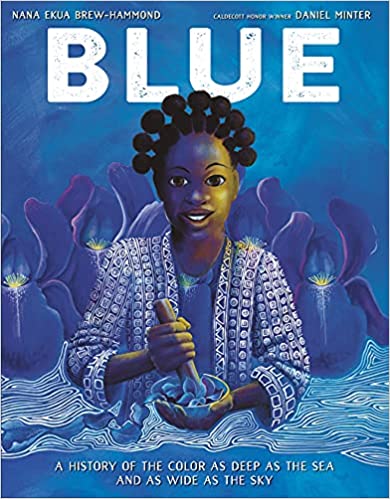

The 2023 Orbis Pictus Award winner embodies Comenius’s belief that all people should be able to have knowledge and scientific achievements through exploring the history of the color blue. Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond takes the reader on a journey through time, traveling throughout the world to rediscover the rich history of the color blue. From the discovery and use of the rock, lapis lazuli, in Afghanistan, to the squeezing of snails and the growing of Indigofera, the reader gets to relive the innovations used to harvest the coveted blue dye, including an inventor being awarded the Nobel Prize for creating a blue chemical dye. From reading this book it is easy to see the impact, for better or for worse, the color blue has had on every society throughout the world.

Maybe because blue has such a complicated

history

of pain,

wealth,

invention,

and

recovery,

it’s become a symbol of possibility,

as vast and deep as the bluest sea,

and as wide open and high as the bluest sky.

Unleashing the Possibility Through Inquiry and the Color Blue

While the book may not be the next Shuri picture book, the book holds the possibility for students to learn about their own culture and others’ cultures through inquiry and the impact the color blue still has in society today. Responding to questions through words and images, students can discover unknown facts about themselves and others that can lead to the celebration of similarities and differences found within different cultures.

After reading Blue as a class or individually, have the students respond to the following instructions on one paper in both written words and drawings:

- Describe what you think of when you see the color blue.

- What are two ways the color blue is used in your everyday life? What does the blue represent? If you do not know what the blue means, you can use your resources to research and discover what the blue means.

- What are two ways in your home is blue used? What does the blue represent? If you do not know what the blue means, you can use your resources to research and discover what the blue means.

This is also an fun exercise that can be done with educators to build a positive community within schools and districts. When a positive community is built, unknown possibilities are released, allowing both students and educators to thrive.

“The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy”

- bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

References

Brew-Hammond, N.E. (2022). Blue: A history of the color as deep as the sea and as wide as the

sky. Alfred A. Knopf.

Lukaš, M., & Munjiza, E. (2014). Education system of John Amos Comenius and its

implications in modern didactics. Život i škola: časopis za teoriju i praksu odgoja i

obrazovanja, 60(31), 32-42.

Moravian Univeristy. (n.d.). John Amos Comenius. Moravian University.

https://www.moravian.edu/about/college-history/john-amos-comenius

NCTE. (2023). Orbis Pictus award. National Council of Teachers of English.

https://ncte.org/awards/orbis-pictus-award-nonfiction-for-children/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed