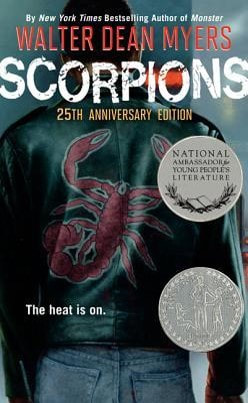

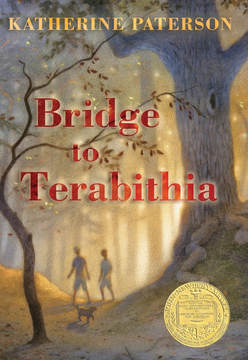

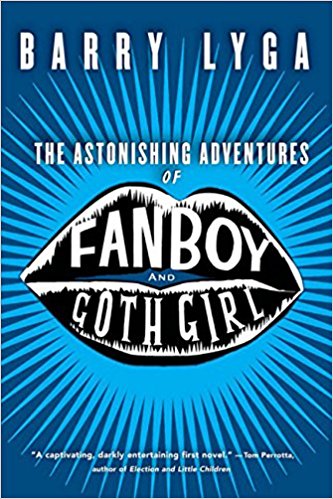

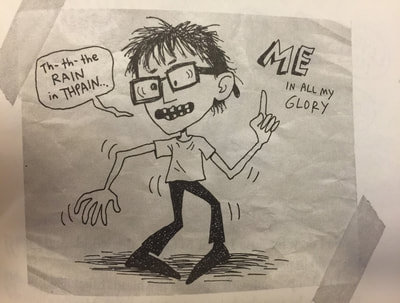

| The best projects arise, unwittingly, from our teaching, don’t they? The one on which I am currently engaged arose from an unintended thematic connection between Walter Dean Myers’ Scorpions (1988) and Bridge to Terabithia (1977), by Katherine Paterson. In the former, we learn that “if there was any one thing that [protagonist] Jamal could do, it was draw” and, later, that he says it’s “fresh” when people stand around watching an artist work in the Village. Instead of noticing and nurturing his talent, however, his teacher asks him to perform menial tasks:

It is only when Jamal shows her the trees he has drawn on a piece of paper—evidence of his ability—that she says he can help when they draw foliage again. In Paterson’s novel, Jesse’s overworked father relies on him to complete chores on their family farm, all but ignoring that he too is a child who also needs affection and acceptance. When Jesse tells him he wants to become an artist, his father growls, “’What are they teaching in that damn school? . . . Bunch of old ladies turning my only son into some kind of a. . .’” Jesse, shocked into silence, does not mention his desire again, daydreaming about drawing as he milks the cows. |

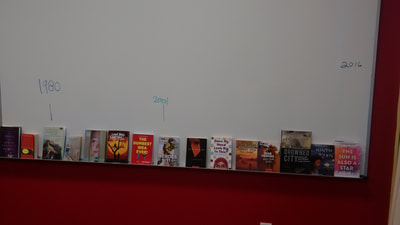

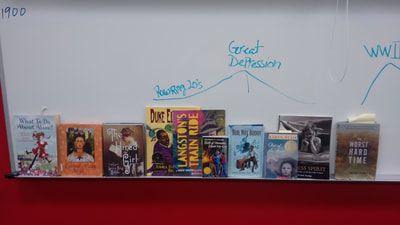

Studying YA’s complicated representation of art, artists, and artistic production over time creates a panoramic snapshot of cultural attitudes towards artistic endeavor. Adolescents and teachers alike can ruminate on these depictions as they determine art’s position in their own historical moment.

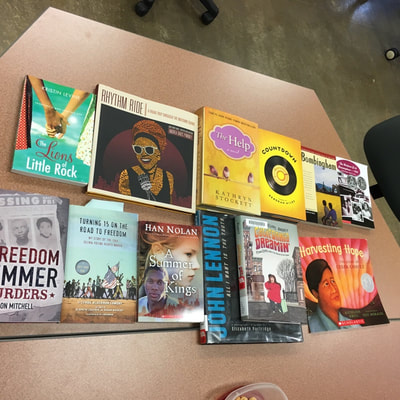

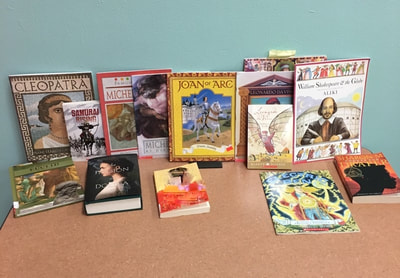

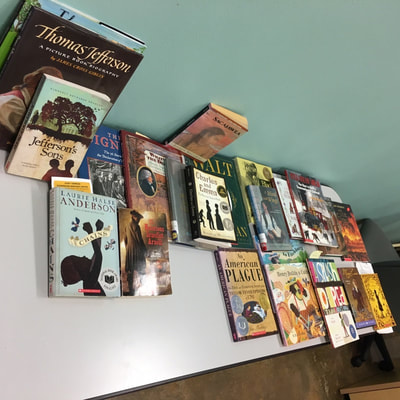

What other YA texts represent art? Follow this golden thread with me by commenting here or using the hashtag #YArt on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed