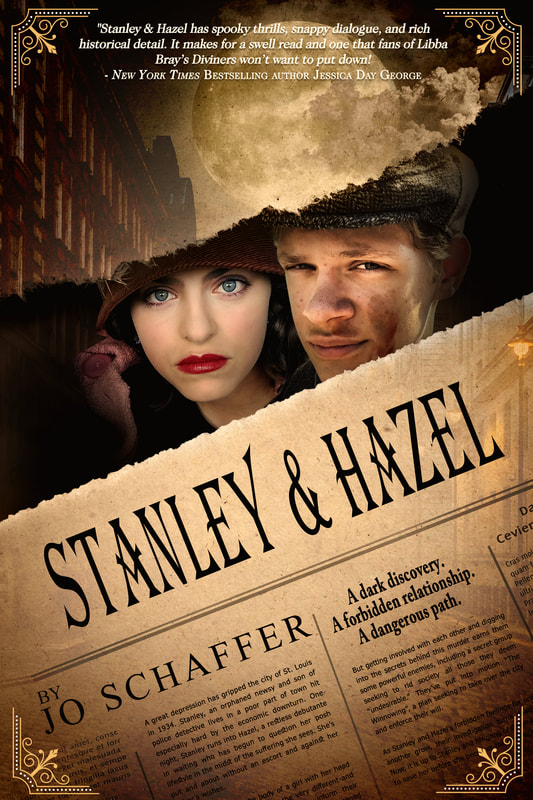

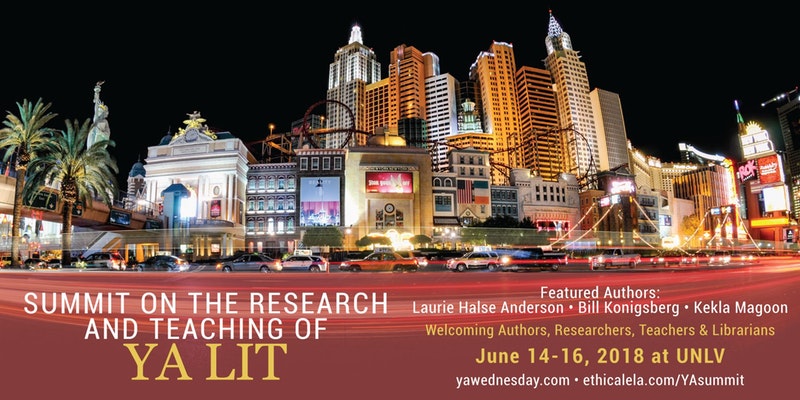

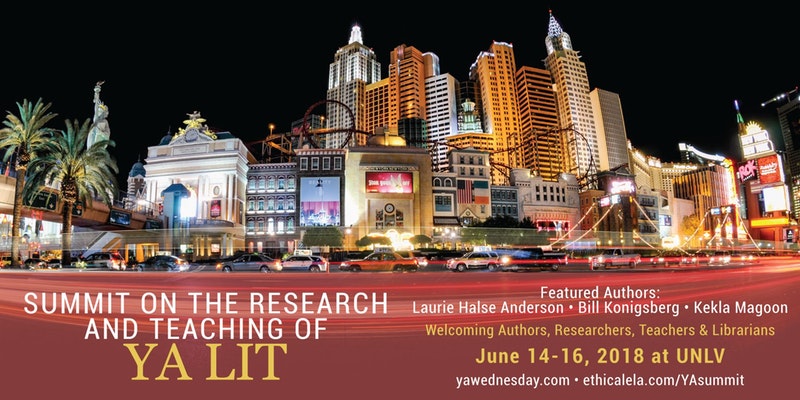

Jo's book, is out this week. Please check out Stanely & Hazel. In addition to writing an essay about history and YA for Dr. Bickmore's YA Wednesday Blog, Jo will be participating in the 2018 Summit on the Teaching and Research of Young Adult Literature. She was also kind enough to answer some interview questions that will be posted at the bottom of the post. She will join a group of established and emerging authors who will be participating in the summit through conversations, reading, and presenting. You can find a list at this link. I am so excited about the opportunity to discuss the state of research around YA literature with such bright and engaging authors. Their contributions will add a great dimension to the conversations that academics, graduate students, teachers, and librarians are all ready bringing to the table.

Take it Away Jo.

| In the book Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, after a vicious attack on a student that involves legends about the founding of the school, the kids at Hogwarts are suddenly interested in history. Normally, they fall asleep to the droning of boring facts and dates by the ghost teacher, Professor Binns. He is surprised and annoyed when the kids pepper him with questions that don’t involve a mathematical recitation of the facts. His quick dismissal of their interest sends the kids back into their academic stupor. As someone who loves history, I’ve always been struck by this scene. The students’ interest in history is related to the sudden relevance of it to their present. The teacher missed an opportunity to use the storytelling power of history. History is more than facts and dates. It's the story of us in all of our beautiful and terrible reality. It contains the power to educate, to make us feel, and to meditate on the human condition. |

For the YA writer, this can be easier said than done. Dystopian novels are a way to use history to engage YA readers. Books like Hunger Games and Divergent often read like “future history” books warning us of what could happen. They aren’t t just fantasies of an impossible future, but rather reflect actual philosophies and movements that have led to the tyranny and horrifying travesties of the past. They serve as cautionary tales for rising generations and show us where our good and bad intentions can take us. Racism, sexism, classism, fascism and xenophobia have emerged in every culture and society throughout history. Ironically, often these things are born of society’s efforts to fix inequality and eliminate pain and suffering until the solutions take on a sinister life of their own.

Dystopian novels can be, sometimes unconsciously, dismissed as “fantasy.” But, novels set in actual history where real events took place, can invite YA readers to contemplate human history and meditate on Winston Churchill’s words, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

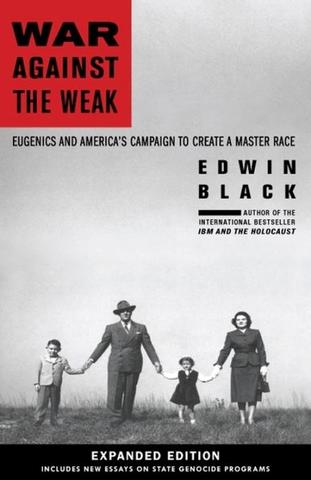

| As I developed the setting, for my YA novel, Stanley and Hazel, I wanted to really delve into this idea. One of the most alarming books I’ve read is Edwin Black’s War Against the Weak. Everyone knows about the horror of Nazi Germany and Hitler’s gas chambers, but many people don’t realize they had their origins on American soil. Black shows in devastating historical detail how Eugenics and the forced sterilization of over 50,000 Americans would eventually become the monster of the Holocaust. Even more disturbing, is that this point of view was shared by The United States Supreme Court, presidents, civic leaders and sadly, even some religious clergy. Eugenics sought to cleanse America of all people deemed “unfit”, “moronic” or undesirable. The rhetoric of the current rise of white supremacy and the alt-right echoes the past too closely for my comfort. I knew I had to put this into the book. History, even if fictionalized, can show us the patterns and thinking errors that lead to injustice and terror. But, at the same time, no one, especially teen readers, want to be preached at while they are trying to enjoy a novel. Story comes first, history lessons second. It’s important to do research, but to only share what is relevant to the story. There is no need to be obvious. The reader, even if young, is not stupid. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed