| Dr. Ashley D. Black is an Assistant Professor of English Education at Northwest Missouri State University in Maryville, MO. She teaches courses in Young Adult Literature, adolescent literacy, and writing pedagogy and is interested in Critical Whiteness Studies and racial literacy development. Her most recent article, “Starting with the Teacher in the Mirror: Critical Reflections on Whiteness from Past Classroom Experiences,” appeared in a spring issue of The Clear House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues, and Ideas. |

As a teacher educator, I consider many factors when selecting texts for inclusion within my Young Adult Literature course reading list; for example, I strive to identify texts that are timely; include literary cohesive representations of YAL as a genre; consider potential for increasing students’ reading interest, engagement and motivation; and focus on inclusivity related to diverse authors and stories. Furthermore, in a saturated YA market, navigating the abundance of published texts can feel daunting, and lists like the Printz Awards provide those searching for new books a good starting point in that search. The impact of the Printz Awards can be linked to the curricular decisions teachers, teacher educators, and librarians make when selecting YA texts for instruction and/or inclusion within school and classroom libraries.

In a previous blog post in July 2020, I wrote about using summer sessions of my Young Adult Literature course to explore the Printz Award Winners. This has been a curricular move I have replicated, and returning to the same text set for several summers has deepened my analysis of both their content and sociocultural contexts. As such, I would like to use this space to share my critical content analysis (Short, 2017), which I am currently engaged in writing, on the Printz Award Winners from the last decade through the lens of Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Critical Whiteness Studies (CWS) (Jupp et. al, 2016). These lenses afford researchers the opportunity to interrupt how whiteness (defined here as a social construction, unearned privilege, and ideology/racial discourse) operates systemically and to challenge conditions of inequity.

This critical content analysis has been driven by the following research questions:

- How have the authors positioned characters of color in the Printz Award Winners from 2012-2022?

- In what ways are issues of race re(presented) within the Printz Award Winners from 2012-2022?

The last decade of Printz Award Winners has recognized stories from diverse authors in a variety of genres that offer YA readers the opportunity to see themselves and those unlike them in authentic ways. The list below includes the text set used for this critical content analysis.

Acavedo, Elizabeth. (2018). The poet x. New York: Harper Teen.

Boulley, A. (2021). Firekeeper’s Daughter. New York: Henry Holt.

King, A.S. (2019). Dig. New York: Dutton.

LaCour, Nina. (2017). We are okay. New York: Dutton.

Lake, Nick. (2012). In darkness. New York: Bloomsbury.

Lewis, John, et. al. (2016). March: Book three. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf.

Nayeri, D. (2020). Everything sad is untrue (A true story). New York: Levine Querido.

Nelson, Jandy. (2014). I’ll give you the sun. New York: Dial.

Ruby, Laura. (2015). Bone gap. New York: Balzer + Bray.

Sedgwick, Marcus. (2013). Midwinterblood. New York: Square Fish.

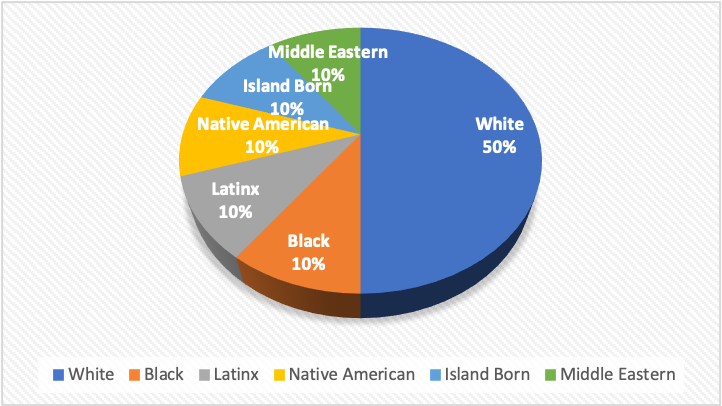

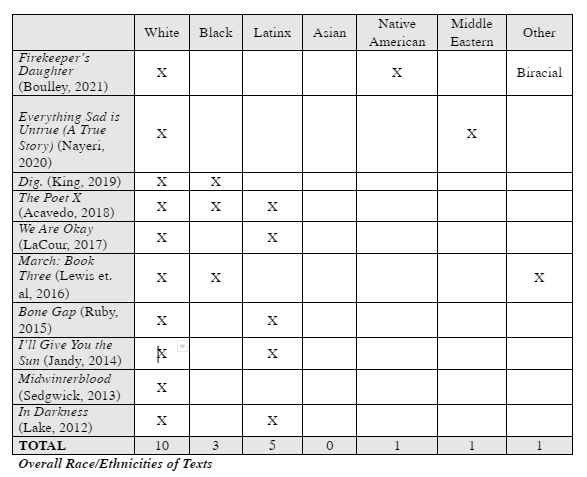

I also considered the racial and ethnic representation outside and alongside the primary characters to include other characters who (1) operate in correlation to the primary character and/or (2) operate to develop the plot.

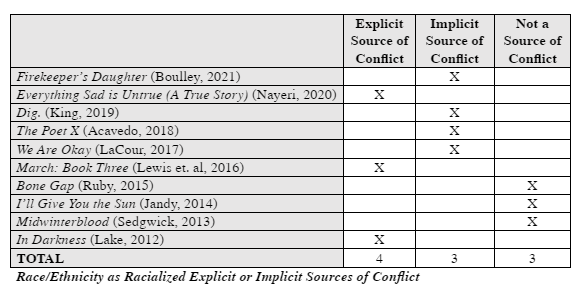

These findings within themselves may not be surprising for YA readers who have noticed a shift in the last two decades towards YA texts seeking to give a voice to marginalized, othered communities. However, when addressing the second research question (In what ways are issues of race re(presented) within the Printz Award Winners from 2012-2022?), I have found a correlation between the race/ethnicity of primary characters and racialized sources of conflict.

Conversely, implicit sources of conflict are ones in which racial issues are subverted, operating as subtext. Boulley’s (2021) protagonist, Daunis, finds herself as an informant for the FBI, investigating meth production and distribution in her Ojibwe tribe. While the investigation itself is not the product of criminal injustice, it highlights the colonized history of Native cultures and the consequences that ensued.

Lastly, the not a source of conflict category represents texts in which racial issues were not a factor within the text even though diverse characters may be present. In Nelson’s (2014) I’ll Give You the Sun, Noah and Jude are white characters dealing with the death of their mother and its effects on their family. Likewise, Bone Gap (Ruby, 2015) centers on the disappearance of Roza within a supernatural Midwestern town.

A cross-analysis of race and ethnicities of primary characters alongside racialized sources of conflict reveals that for the five texts that include primary characters of color, racialized conflicts are present, both explicitly and implicitly. There is not one text within this list with a primary character of color whose central conflict that does not revolve around issues of race. Yet, for the other five texts featuring white primary characters, only one (Dig., King, 2019) contains an implicit racialized source of conflict and is a non-factor in the other four texts in this category.

These findings might lead us to ask: why are white characters immune from racialized conflict while characters of color are not? How might white character centric texts reinscribe issues of white supremacy and privilege by lacking cultural or ethnic characteristics? How do diverse representations within this text set challenge the notion of the “single story”? How might these stories, grounded within racial conflict and/or trauma, affect our students of color?

I do not have answers to these questions, but I am working through them alongside my pre-service teachers who will one day enter middle and secondary English classrooms. When they do, I hope they are able to select texts that are both challenging and comforting to their future students. I hope that they seek out authors and stories that are varied and layered and lead to deeper levels of understanding. Lastly, I hope that they interrogate award winning lists with a critical eye.

References

ALA American Library Association. (2022). The Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. YALSA. https://www.ala.org/yalsa/printz

Jupp, J. C., Berry, T. R., & Lensmire, T. J. (2016). Second-wave white teacher identity studies: A review of white teacher identity literatures from 2004 through 2014. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1151-1191.

Short, K. G. (2017). “Critical content analysis as a research methodology.” In H. Johnson, J. Mathis, & K. G. Short (Eds), Critical content analysis of children’s and young adult literature: Reframing perspective (pp. 1-15). Routledge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed