It Takes a Village to Raise a Monster: Horror about Surviving Adolescence by June Pulliam

Carrie, Stephen King (1974)

| Although it was published over 40 years ago, Stephen King’s novel Carrie is still an accurate representation of the experience of being the bullied and slut-shamed girl in high school (minus the protagonist’s telekinetic abilities). Carrie, who is described as “the sacrificial goat, the constant butt, believer in left-handed monkey wrenches, perpetual foul-up,” is the most bullied girl in Chamberlain, Maine. Carrie’s outsider status is due mostly to her mother’s religious mania. It’s bad enough that Margaret constantly tells her neighbors that they are backsliding and hell-bound due to their comparative secularism. Margaret also raises Carrie in a way that makes it difficult for her to fit in with her peers. Carrie is teased by her peers on the first day of school after she naively prays before eating lunch. Also, Margaret makes Carrie wear skirts that are too long or plain to be fashionable, and prohibits her from wearing bright colors, especially red, which Margaret describes as the color of sin, and Carrie must make a special effort to have a passing understanding of popular culture as there is no television or popular magazines in the house, and Carrie can only listen to popular music on the radio when her mother is not home. Even mirrors are forbidden in the White household, and Carrie is allowed only the most rudimentary grooming products, so as a teen, she is a “frog among swans” with her greasy, lifeless hair and acne. But worst of all, Carrie is not safe at school or at home, where she faces verbal and physical abuse of some sort from everyone, including her mother. At home, Margaret routinely locks Carrie in the closet for hours to “repent for her sins” after the slightest disobedience or beats her. At school, the bullying she endures ranges from name calling to being tripped in the aisles and having her books knocked out of her hands by other kids. The emotional harm done to Carrie by her mother and peers is compounded by the location of the story, the small town of Chamberlain, Maine, and prevailing attitudes about bullying and child abuse at the time. Chamberlain is so small that she cannot escape her tormentors by simply changing schools. Also, in the 1970s, neighbors rarely intervened in suspected cases of child abuse, believing that a parent’s disciplinary practices were none of their business, and school administrators were not trained to spot the signs of abuse and had little knowledge of the lasting harm it does. Bullying too was mostly ignored in the 1970s, when experts still believed that it was best for children to sort out their own problems by confronting their bullies, not realizing or caring that this is not an option for many victims. So Carrie’s resulting anger on Prom Night after her peers’ play the most cruel joke on her yet is not surprising. Carrie’s telekinetic abilities, that are unknown to her peers, or even fully to Carrie until her sixteenth year, give her the ability to translate this anger into violence—and she literally burns the town to the ground before the exertion required to use her mind to move matter to this degree is so stressful on her heart that she dies. |

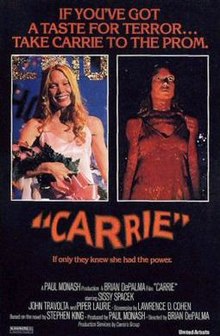

King's novel vs de Palma's film

| King’s novel is superior to Brian de Palma’s 1976 film of it, which the novel’s paramaterial. Carrie’s story is not written as one, fluid account related in the first-person or by an omniscient narrator. Instead, King tells the story of Carrie in retrospect, after various experts and journalists have investigated the event and weighed in about the event. A combination of scientists and experts in the paranormal agree that Carrie’s powers were a one-off, and so the world is safe after her death. Their conclusion is typical of stereotypical horror of the time, where the monster is always vanquished. However, Carrie’s last pages resist narrative closure in the form of a poorly spelled letter from an Appalachian woman describing her infant to her sister. The child shows signs of being telekinetic, a trait she has inherited from her female relaitves, as the letter’s writer makes reference to a grandmother who had the same ability, though she did not use her powers to kill anyone. Because this girl lives in a part of the United States that is underserved by medical and scientific experts, it is possible that she might develop her telekinetic abilities before anyone who could understand their dangers might intervene. |

The Girl with All the Gifts, M. R. Carey (2014)

| The Girl with All the Gifts is a retelling of the zombie apocalypse along George Romero’s (Night of the Living Dead, 1968) and Richard Matheson’s (I Am Legend, 1945) pandemic models. However, the zombie in this case is not a devolved form of our species who have been turned into mindless consumers (of flesh), but a post-human creature whose emergence is a positive evolutionary leap, though it still brings about the fall of civilization and the death of most of the human race. In The Girl with All the Gifts, most humans have become infected with a fungus that turns them into mindless fiends whose strongest drive is to consume human flesh. Just the smell of human saliva can provoke one infected, or “hungries” as they are called, into a feeding frenzy. Anyone bitten by a hungry but not killed will also turn into a hungry, although one does not resurrect as a hungry after dying from natural causes. A team of scientists led by Dr. Caroline Caldwell are holed up in a bunker with a set of special captive hungries, those who were born to mothers who were infected during their pregnancy, and who have matured as human children do and seem capable of learning. The early adolescent hungries are taken from their cells every day in restraints and placed in a classroom to be taught by Miss Justineau so that the head scientist can determine which hungries are the smartest and then euthanize them and dissect their brains in order to find a vaccine for the remaining number of the living who are uninfected. The precocious Melanie is Dr. Caldwell’s next target as she is much more intelligent than most humans. She can effortlessly memorize complex facts such as the chemical composition of a compound, and she is also able to understand the Greek mythology that Miss Justineau teaches the class and use it to inspire a story of herself as a modern-day Pandora, as well as a new type of being who transcends biological categories in order to save her beloved teacher from other hungries. Miss Justineau, the only human character in the story who cares about her charges, is so moved by Melanie’s story that she touches the girl on the head, which prompts the guards to sweep into her classroom and haul her away for punishment, and then take Melanie to the lab for dissection. |

Melanie is unique as a post-apocalyptic survivor. Instead of the usual heavily-armed white man who is able to fend for himself amidst the ensuing chaos of the zombie apocalypse, Melanie is a post-human young woman of color, a blending of several categories of Otherness. Perhaps this is what makes her uniquely able to survive in this new world. Like other hungries, Melanie has a human form, since the zombies in The Girl with All the Gifts are not undead, or reanimated corpses in various states of decomposition. Too though, Melanie’s ability to control her urge to feed off of humans has allowed her to view them as something more than a meal. In this way, Melanie is post-human, a newer version of the old model who transcends the binary categories on which human civilization was founded including gender, race, age, and species, to name a few.

The novel ends with Melanie and Miss Justineau in a sort of parent/child, teacher/student relationship, but it is not clear who fills each role, since Melanie must parent Justineau sometimes to protect her from uncontrolled hungries. Also, while Miss Justineau is now teaching the group of child hungries that she and the rest of the crew discovered before all but herself were killed, she does so behind a protective plastic shield while Melanie disciplines her fellow hungries so that they are amenable to being taught. In this way, The Girl with All the Gifts reimagines our present world, with its political and environmental stability that make it appear to be on the brink of calamity just when young people are ready to take over from their elders. Perhaps the end of the old world as the elders see it is the beginning of one where the social structures that have caused these calamities in the first place will be eliminated in favor of something more sustainable and egalitarian.

Blood Crazy, Simon Clark, (1995)

| This is an old novel, and certainly not as genre-defining as King’s Carrie, but it’s one of the best works of horror that I have ever read about teens, and it’s still available to read as a Kindle book. Blood Crazy is a sort of post-apocalyptic Lord of the Flies. On an otherwise uneventful Saturday, Nick Aten observes that one of those events that cleave time into “BC/AD” occurred: Something changes the brains of everyone over 21 so that they now view all young people as enemy species who must be killed. A world-wide murderous rampage ensues where many of the young are murdered by adults, and the remaining young people hide and protect their younger siblings. Because civilization collapses overnight, each new day is a challenge for finding food and potable water and safe shelter. Nick falls in with a group of youth who have sheltered in a compound that they have secured and provisioned. All is comfortable for a few weeks before Tug Slater, bully extraordinaire, and his droogs, seize control. With little to keep his worst impulses in check, Slater is in a better position to terrorize other members of the compound, who are only allowed to stay and be fed if they prove useful or amusing. Slater, a Negan (The Walking Dead) wanna-be, forces many of the teen girls to be part of his harem, and finds inventive ways of tormenting those who annoy him. One girl, whom Slater dislikes due to her love for her dog, is forced to play “carry the can,” a game where the unlucky participant has an IED strapped to her neck and must find the key to remove it before it explodes. When Slater straps an IED to the girl’s dog and deliberately does not give her enough time to save her companion, she opts to embrace her dog so they will die together. Unable to fight Slater alone, Nick escapes the compound to brave the ruined landscape and roving bands of transformed adults to locate survivors and possibly answers about what has happened to his species overnight. Clark’s infected/affected adults bent on murdering the young externalize an ugly reality that all young people have probably felt to some degree—that some adults might want to kill them. As well, Blood Crazy is like some of today’s best YA dystopian fiction in its depiction of teens shouldering responsibilities that even most adults would find too challenging. But Nick and other of the good teen characters in this novel rise to the occasion perhaps because they are so young—their lack of experience makes it difficult for them to understand the possible dangers, a condition that makes it easier to do a serious but unfamiliar task. Finally, like Carey’s The Girl with All the Gifts, Blood Crazy has a hopeful ending. After making what is essentially a hero’s journey, Nick returns to the compound in a better position to liberate it of Tug’s tyranny, making their small world safe for the other inhabitants and his infant son he has fathered with his girlfriend. Whether or not this small community can survive remains to be seen, but it is run on the principles of communitarianism and egalitarianism that will prevent the creation of social hierarchies that create winners and losers with unequal access to resources. |

Until next week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed