Alan Brown and Luke Rodesiler will be talking more about the book in a Live Web Seminar produced by NCTE called “Critical Literacy at the Intersection of Sport and Society” this week on February 23rd.

| As I entered the classroom my eyes immediately gravitated to his Oregon O. The year was 2013, it was the second week of January, and Chip Kelly’s Oregon Ducks had just claimed a Fiesta Bowl championship, ending the season as the number two team in the nation. Anyone who knew anything about college football knew it was a beautiful time to be Ducks fan—a bond that the kid in the Oregon hat and I shared. I had come to this particular high school classroom to do some research with struggling adolescent readers, which was where I met Dylan, the fan in the Oregon hat. Turns out he wasn’t just a football fan—he was also a football player. His 230 pound, 17-year old frame mostly fit in his desk and he talked willingly about his team as well as his performance at the state wrestling tournament the previous year. He also spoke proudly of his Native Americana heritage, his mother’s and sister’s experiences as college athletes, as well as obstacles that prevented them from finishing. He hoped to follow in their footsteps one day and compete in intercollegiate athletics, but also to finish his degree. However, with a smile and a chuckle he recognized finishing may pose a challenge because of one problem: he didn’t like to read. Dylan struggled a lot in his classes, partially, he said, because he didn’t enjoy reading and he never finished books. But before I could probe into the “whys” behind these statements, he paused and thought for a moment. I waited. He then explained that he had actually finished one book, a YA novel given to him by his teacher called Gym Candy by Carl Deuker. He then detailed the story of a freshman football player driven to succeed. Amidst the athlete’s preparations, a personal trainer suggests he take supplements, which led to steroids, and then to a dramatic life-or-death struggle. As Dylan completed his commentary on Gym Candy, he shared his opinions on steroid use, the complexity of the situations characters faced in the novel, and his assessment of the book. Without much of a break he then proceeded to tell me that he was also reading a nonfiction book called When the Game Stands Tall: The Story of the De La Salle Spartans and Football’s Longest Winning Streak by Neil Hayes. The book, which had been assigned reading for his football class (you have to love a high school coach who actually makes reading a part of football class, right?), detailed the real-life experience of a California high school football team that won 138 consecutive games. Similar to the details he shared about Gym Candy, Dylan—my self-proclaimed non-reader—freely and articulately shared highlights, stats from and his opinions about When the Game Stands Tall. |

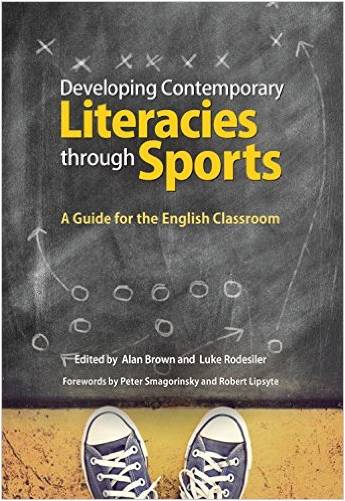

| Later, as I reviewed his transcript, I noticed that Dylan provided almost a page of typed, single-spaced commentary detailing these books, his reactions, and his analysis. Dylan really was a reader—or, at least he was a reader when teachers connected him with young adult fiction and nonfiction titles that provided opportunities for him to think critically about topics he loved. It was students like Dylan who prompted my initial interest in Alan Brown and Luke Rodesiler’s project that recently resulted in the book Developing Contemporary Literacies Through Sports: A Guide for the English Classroom published by NCTE. In this edited collection, Brown and Rodesiler draw on the work of English education scholars, young adult authors, teachers, and researchers to weave together both a compelling rationale for the inclusion of sports in the English curriculum, as well as lesson ideas to help teachers and students probe the impact of sports culture. Centered on interrogations of power, bias, and dominance in the sports, the editors introduce the phrase critical sports literacy (xxiii) to describe approaches that critically examine, deconstruct and interrogate sports and sports culture. In the seven sections that follow, teachers and researchers share ideas for implementation that focus on facilitating literature study, providing alternatives to traditional novels, teaching writing, engaging students in inquiry and research, fostering media and digital literacies, promoting social justice, and developing out-of-school literacies. |

| In addition to tapping these compelling and powerful young adult novels, the contributions in Brown and Rodesiler’s book also invite teachers to incorporate other sports-based texts into these critical inquiries. As Dylan’s love of When the Game Stands Tall demonstrated, nonfiction sports-based texts appeal to readers and many of the ideas presented in the lesson ideas center on inquiries driven by nonfiction texts. For example, Quentin Collie and Geoff Price describe how podcasts from Grantland, ESPN, and other sources work as mentor texts to help students create their own sociopolitical commentaries that they produce as podcasts. Another chapter by Lisa Beckelhimer invites students to use pieces such as “If It Ain’t Rubbin’, It Ain’t Racin’: NASCAR, American Values, and Fandom” and other articles available through EBSCO, as well as documentaries and other sources to help students question the role of culture and context in sport. Also drawing from a range of print and film nonfiction sources, Ryan Skardal uses excerpts from Britney Griner’s memoir In My Skin: My Life on and off the Basketball Court as well as interviews, articles, and media footage to identify connections between authorship and identity. It’s among these chapters that I’d situate my own contribution to the book that invites students to research the true stories behind the reel adaptations of many of sports most famous onscreen moments. |

At the close of each section, the voices of well-known YA authors bring the reader back to where we started—with stories that demonstrate the impact sports can play in learning. Bill Koningsberg’s “Fag on the Play,” details a very personal experience that served as the inspiration for a scene in his novel Openly Straight while posing questions about our readiness to raise diversity questions in the classroom and on the field. Chris Lynch’s author contribution details his own experience with sports literature and its value for reluctant readers. Other contributions written by authors Ann E. Burg, Chris Crutcher and Rich and Sandra Neil Wallace speak powerfully to the larger thesis of the book. And as I read Alan Lawrence Sitomer’s description of Gerald, the high school basketball star, and his conflict with an English teacher, I am reminded of a scene not unlike others that play out across the country as students and teachers view the mental activity of reading as being at odds with the physical activity of sports—which brings me back to Dylan.

If we want students like Dylan to venture into our literary worlds and develop the literary skills we value, an approach that considers sports and sports culture, as highlighted in Brown and Rodesiler’s book, is one worth exploring.

Dawan can be contacted at: dawan_coombs@byu.edu

RSS Feed

RSS Feed