I will recap #ALAN19 more next week. (Don't we all need a Thanksgiving Break?) If you have a short paragraph of one of your favorite moments, please send it to me as I prepare for next week. Adding a photo would help as well.

In brief, I am so thankful that Padma Venkatraman and Andrea Davis Pinkney for providing a foundation for Monday and Tuesday. All of the solo speakers were spectacular.

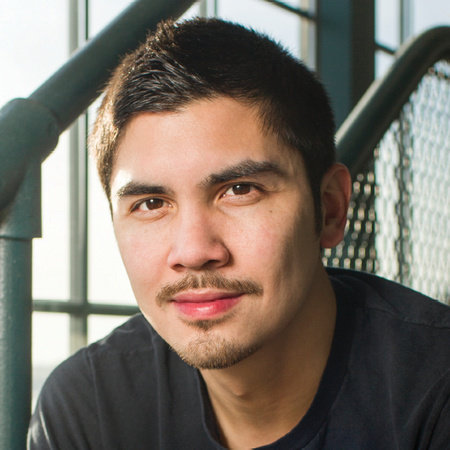

Check out Randy Ribay

Check out the

UNLV 2020 Summit on the Research and Teaching of YA Literature

| | |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed