Jeff has written for the blog several times and frequently it is during this time of year. In part, that is due to the fact that Jeff has studied banned books and censorship in the classroom. Clearly, today is a departure from that topic, but you can revisit his earlier posts at these links: one, two, three, and four.

Once again, thanks for these wonderful remembrances.

Two Remarkable Teacher Educators:

Teri Lesesne (1952-2021) and M. Jerry Weiss (1928 – 2021)

by Jeff Kaplan

I can’t imagine, though, that would be true if they had taken courses with these two engaging and inspiring educators. Teri Lesesne and Jerry Weiss dedicated their lives to ‘pushing good books for good kids’ – never ever dreaming that kids did not like to read. Both thought – quite rightly – that getting kids to read was just a matter of ‘finding the right book for the right kid’. Nothing more. Nothing less.

And, oh yes – they both were guided by this - that ‘that kids read’ was more important than ‘what kids read.’ And that is a small club. As they knew so wisely, most of traditional education – elementary and secondary – public and private – and even college – is spent telling kids what to read – and not asking them – “what do you like to read?”

And both knew – that if only teachers would ask their students that one question – “what do you like to read?’ – the world would be a different place. At least, in public schools.

Teri Lesesne (1952 – 2021)

A Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, native, Dr. Lesesne lived in Texas all her adult life. She graduated from the University of Houston with an Ed.D. in 1991. After teaching in middle school for fifteen years, she became a professor at Sam Houston State University, where she was affectionately known as Professor Nana. She taught in the Department of Library Science for the greater part of thirty years.

Teri Lesesne published three books: Reading Ladders (Stenhouse, 2003) Making the Match

(Stenhouse, 2006), and Naked Reading (Heinemann, 2010). A fourth title, co-authored with Donalyn Miller, is forthcoming. To this day, her books are widely read and used by teachers and educators advocating for adolescents to read books of their own choosing.

Known by her peers as the “Goddess of YA Literature” or “The Book Lady” for her unparalleled knowledge of young adult literature, Teri touched the lives of many young authors, current and future librarians, and countless others and was especially passionate about connecting YA books to readers. She was known for saying that “the right book given to the right student at the right time would create a reader.”

“Yes, Teri was fiercely opinionated, wildly independent, and willing to wear purple hair long before she was ever considered anywhere old enough to do such a thing (or so the poet Jenny Joseph would say). She laughed quickly, squinted her eyes and dismissed stupidity with a glance when stupidity was indeed looking us in the face, and never, never ever, backed away one bit from teaching, preaching, and celebrating the power of a book in a person’s life. She understood that books offer ways out and ways in; ways to become and ways to celebrate being; ways to grow beyond who we are into people we didn’t even know we had dreamed of becoming.”

During her many presentations, Teri Lesesne said she learned just as much from her audience as her audience did from her. “I try to make it [professional development] as painless as possible. I spent fifteen years listening to others do professional development and I learned from all the presenters what and what not to do. I tend to be fairly informal and rather flippant. I tell jokes and stories about myself and my experiences to illustrate points I am trying to make.”

Teri Lesesne was a voracious reader, and her reading became the knowledge for her own books, articles, columns, blog posts, keynote speeches, and many, many workshops attended, over the years, by tens of thousands of people. And that work turned into recognition from national and state organizations (National Council Teachers of English, Executive Secretary of the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents, International Literacy Association), and being named a Distinguished Professor of Library Science, and now a Distinguished Professor Emerita of Library Science from Sam Houston State University.

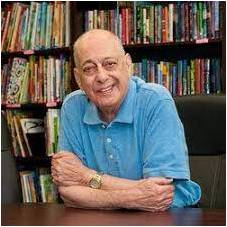

M. Jerry Weiss (1928 - 2021)

Born in Oxford, North Carolina, Dr. Weiss completed his undergraduate work at the University of North Carolina and earned his Master of Arts and Doctor of Education degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University. He taught English, language arts, and reading in secondary schools and colleges in Virginia, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, and New Jersey and conducted workshops throughout the United States, in London, Canada, Dublin, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Scotland.

Jerry Weiss was the author and editor of countless books and articles; an advisor and editor for many publishers and on a variety of reading series; a leader for numerous state and national professional organizations including serving as president of the New Jersey Reading Association, the National Council of Teachers of English, the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents, and the International Reading Association. Dr. Weiss received the International Reading Association's Arbuthnot Award and the International Reading Association's prestigious Special Service Award. In 2006, the New Jersey City University created and dedicated the M. Jerry Weise Center for Children’s and Young Adult Literature in his honor.

In addition to encouraging the use of trade books and guiding new writers, Weiss fought censorship nationally (having been fired from his first teaching job for using books deemed unsuitable for young people to read) and served as an educational consultant in many countries and for many publishers. As one of the earliest proponents of diverse books, Weiss often said, “To meet the diverse and changing interests, needs, and abilities of students, we must bring new books into classrooms. Good books make meaningful reading happen” Weiss also lamented that the national obsession with standardized testing, insisting that testing “has little to do with the impact of learning upon the learner,” while always emphasizing that “children enter the classroom with different abilities, interests, experiences, attitudes. We can’t expect any one method or set of materials to meet their needs.”

Concluding Remarks

And that is why – teacher educators – really good teacher educators – people who not only know their ‘stuff’ about teaching and learning – but motivate others to think long and hard about what they ‘do’ in the name of teaching – especially for young people – are so precious and few.

Teri Lesesne and Jerry Weiss were those precious and few. They defied convention. They defied tradition. They defied curriculum mandates and principals and teachers and politicians and ordinary people who believe that young people should read the classics and ‘get on with it.’ They defied those who want kids to read, “Nothing controversial. Nothing upsetting. Nothing funny.”

We are indebted for their work – and their defiance of conventional odds – and for their becoming the teacher educators they were – and to this day, - for those who knew them, like myself, and for those, who knew of them only in passing - may their legacy and memory be a blessing. Amen.

Lesesne, T. (2010). Reading Ladders: Leading Students from Where They Are to Where We Want Them to Be. Heinemann.

Lesesne, T. (2006). Naked Reading: Uncovering What Tweens Need to Become Lifelong Readers. Stenhouse.

Lesesne, T. (2003). Making the Match: The Right Book for the Right Reader at the Right Time: Grades 4-12. Stenhouse.

Weiss, M. J., & Weiss, H. S. (Eds.) (1980). More Tales Out of School. Bantam

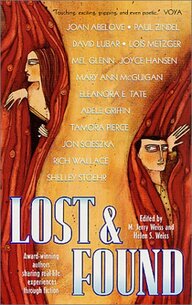

Weiss, M. J., & Weiss, H. S. (Eds.) (2000). Lost and Found. Forge Books.

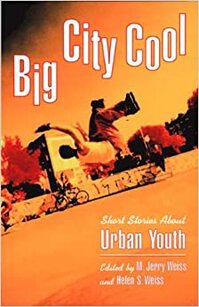

Weiss, M. J., & Weiss, H. S. (Eds.) (2002). Big City Cool: Short Stories About Urban Youth. Persea.

Weiss, M. J. (Ed.) (2004). The Signet Book of Short Plays. Signet.

Weiss, M. J., & Weiss, H. S. (Eds.) (2009). This Family is Driving Me Crazy. Ten Stories About Surviving Your Family. Putnam Juvenile.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed