Updated!! 9/11/2021

Perhaps her most important posts have been those associated with 9/11. Without question, there are events in our lives that become markers because of their impact on society. For me, I remember clearly three crucial events -- The assassination of President John F. Kennedy, when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, and when planes struck the twin towers on 9/11/01. All three shaped how I see and respond to people and the world we inhabit. (I am quite sure the day Covid 19 began to personally effect my life --March 12, 2020-- will be another.)

9/7/2018: Eleven Novels for Nine/Eleven: Studying & Discussing 9/11 through Diverse Perspectives” by Lesley Roessing

9/9/2019: 15 Novels to Generate Important Conversations about the Events & Effects of Nine Eleven by Lesley Roessing

9/9/2020: Examining the Events of September 11th through MG/YA Novels by Lesley Roessing

These year is the 20th time we will recite the names of those we lost. We have to acknowledge that non of the students in our k-12 schools were not alive, yet the consequences of those reverberate through their live in a variety of ways. In politics, in immigration policies. and in armed conflicts, just to mention a few. Of course, we must consider the lives of people who lost family and friends.

This year Lesley marks the event by reviewing more books and collecting some comments by YA authors who have written about that fateful day.

20 MG/YA Novels to Commemorate the 20th Anniversary of 9/11

(+1 Graphics Collection)

by Lesley Roessing

On this 20th anniversary, the incidents of September 11, 2001 are still vivid in the minds and hearts of those who experienced and were able to comprehend these events. Many of our students have still not learned about the events, and many others do not realize the impact of those events on their world. One of the most effective ways to learn about any historical event, and the distinctions and effects of that event, is through a novel study—the power of story.

| I have found the most effective way to confront difficult topics while still presenting a variety of perspectives and differentiated reading experiences for our diverse readers is through reading in book clubs. It has been eye-opening—and rewarding—to visit schools and facilitate book clubs using novels written about the events of 9/11 from differing perspectives. When classes read 5-6 novels about 9/11 in small groups of students who are collaboratively reading, they can access differing perspectives to a story and generate important conversations within each book club and between book clubs. Book clubs gives readers safe spaces to discuss sensitive topics and their own feelings. A complete unit on this topic for English-Language Arts and Social Studies classes is outlined—with daily focus lessons and student examples—in chapter 10 of Talking Texts: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum |

I asked some of the authors three questions, requesting that they choose one to answer. I share their fascinating answers.

- Jewell Parker Rhodes, author of Towers Falling

- Wendy Mills, author of All We Have Left

- Gae Polisner, author of In Memory of Things

- Tom Rogers, author of Eleven

- Kerry O’Malley Cerra, author of Just a Drop of Water

- Nora Raleigh Baskin, author of Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story

- Julie Buxbaum, author of Hope and Other Punchlines

- Catherine Stine, author of Refugees

1. How/Why did you decide to write a novel about the effect of 9/11

Most story ideas emerge over time, but I can pinpoint the birth of Eleven to September 11, 2008. My nephew was visiting us in California and asked, "Uncle T, what's the big deal about 9/11?" His question shocked me at first, but a bit of digging revealed that schools weren't teaching about it; the topic was too fraught, and there were almost no books for kids to help tell the story of that awful day. Ironically, my nephew had just interviewed an older friend of mine, a Holocaust survivor who speaks to schoolkids about his experience so that humanity will never forget. I realized we need to be telling the story of 9/11 to future generations so that we, too, will always remember how the world changed that day.

After 9/11, and pretty much for the first time in my life, I was having a hard time coping. I had young children at home and suddenly didn't feel our world or country was safe for them anymore. Of course, in my earliest childhood, I was raised against a backdrop of, and always well aware of, war as my father was a young M.A.S.H. surgeon in Viet Nam, gone for a whole year. But beyond that, my childhood had felt safe and our country was in a peaceful and prosperous period where it -- we -- all felt pretty invincible. Until 9/11.

For weeks after, then months, that stretched closer to a year, I felt scared and off balance. Living under an hour from my beloved NYC (where I had lived pre-children), I didn't want to go in, ride over the bridges, visit landmarks I had loved. I was searching for ways to cope, and my brain started telling me to write about it. Write it out in story, with characters who are resilient and figure out how to rise against the immediate backdrop of destruction and despair. And so were born Kyle and the bird girl. Only typing this answer now does the "bird rising" connection even come to me.

2. How did you decide on the perspective your novel presents or the characters/setting you created to tell the story of the effects of 9/11?

The primary emotion we associate with 9/11 is grief and anger, but when I decided to write this story, I knew I wanted to shine a light on the incredible bravery and strength of the people trapped in the Towers, as well as the families dealing with the loss of their loved ones. I thought it was important to remember that on one the darkest days of human history that there were still these bright moments of light, of humanity. Alia’s story showed us the extraordinary courage of ordinary people that day, and I chose Jesse and her family, fifteen years after the events, to symbolize one family’s journey from grief and anger to ultimately a place of acceptance and forgiveness.

I wanted to write a story that showed how important that day was to our country, but also to show the strength of the human spirit in the face of tragedy.

I love fifth graders! Selecting three fifth grade characters was an intentional choice. In eight years, they will be old enough to vote and defend our country. They need to know America’s history, past and recent. Because adults are traumatized by 9/11 memories, we have steered conversations away from this pain. But we need to be strong and engage children. Essentially, all youth born post-9/11 are, nonetheless, experiencing its’ traumatic legacy.

In Towers Falling, Deja, an African American, experiences homelessness because her father, a survivor, has psychological trauma and is unable to work. Her family, too, represents how mental health and medical bills are the leading cause of homelessness. Her friend, Ben, is Jewish American and a New York transplant from Arizona, because his parents are divorcing. His father’s repeated deployments and PTSD has fractured his family but not his empathy for his friends. Sabeen, a Muslim-American, represents how post 9/11, religious prejudice and the scapegoating of Muslim Americans as terrorists, continues.

Sabeen, Ben, and Deja with their open hearts and curiosity embody the foundational American values of immigration, religious tolerance, and “liberty and justice for all.”

In September of 2001, I, along with the rest of the world, watched in horror as the attacks on New York City, The Pentagon, and in the sky over a tiny Pennsylvania town unfolded; yet as heart-wrenching as it was to watch on TV—I was glued to my TV for days—I was also swept up with the sense of patriotism that swelled deep for months after. Everywhere I turned, red, white, and blue saluted people across town from t-shirts, to pins on our lapels, to flags boasting in the sky. Neighbors–who usually came home, pulled into their garages, and closed their doors–suddenly stopped in their front yards to talk. People came together in ways I’d never experienced before.

Within a day or two of the attacks, my alternating moods of anger, sadness, and pride suddenly had a new emotion to deal with. Fear. It was discovered that Mohammad Atta, the hijacker of American Airlines flight 11, lived just around the corner in my smallish town of Coral Springs, Florida—over 1,000 miles away from the closest attack. What if I’d seen him around? What if my family and I had eaten next to him at a restaurant? It stunned me to the core.

It didn’t take long for more of the details involving that day to emerge. It seemed Atta and several of the other hijackers had made their way around South Florida unassumingly for months. But when it leaked that these men had taken flight lessons in Venice, Florida, and it was believed they’d had help from fellow Muslims living there, hundreds of “what ifs” began to haunt me. Every single one of them boiled down to the final, What if my friend’s parents had helped these men?

My friend was someone I’d met in college. He had come to the U.S. to study and get away from the strict Islamic rules of his upbringing, if only for a while. We grew close, and eventually my sister, my boyfriend, and I went to visit his devout Islamic family abroad, where his parents welcomed us into their home and treated us like old friends. A few years later, wanting to be closer to both of their boys who were then living in Florida, the parents decided to move to the states—Venice, Florida to be exact.

Flash forward to the days following September 11, I found myself doubting my friend’s family when I’d heard they were being questioning in connection to the attacks. Had they helped these terrorists somewhere along the way? I’d love to say I believed they were innocent, but I’d be lying. It took me a day or two to really know in my heart that they weren’t involved. Not these loving, welcoming people. I hated myself for having ever wavered in my thoughts of them to begin with, but the emotion of that tragedy ran deep. The emotion and fear of those days controlled me.

Not long after, I talked to my friend and asked how he and his family were doing. He told me that the FBI had cleared his parents, but life had become difficult for all of them. I listened to him talk, and though I didn’t admit it to him then that I had doubted them myself, he knows now. So do his parents, and I cannot thank his father enough for reading several drafts of this book and helping me get it right.

The feeling of regret stuck with me for a long time. Being a teacher, I looked at kids around me who rarely saw racial lines, and I wondered if this boy—my college friend—and I had been younger when September 11 happened, would I have ever doubted his family? Would I have had the prejudice that seemed to come with age? I began asking questions to anyone who wanted to discuss the subject. Soon I was taking notes, scouring the Internet, and reading books; I was amazed to learn that many non-practicing Muslim kids in the United States actually turned to mosques for answers following 9/11. The basis for my story developed in my head before I even realized I was writing it.

As a former history teacher, this was a story I knew needed to be told. It’s the type of novel I myself would have used in a classroom to supplement the textbook and to show kids, who didn’t experience that day firsthand, the enormity of the event that happened on our own soil and took thousands of lives—six of them from my own small town, a thousand miles away. I want children to know that sentiments changed from minute to minute, teetering between patriotism, alarm, grief, and so much more. One of my favorite scenes in the book is the one where Jake and his dad attend a memorial service three days after 9/11. That event is real. It moved me the same way it moved Jake. I hope it moves you, too.

When I started writing Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story, I knew exactly how many characters there'd be, who they'd be, and in what setting I needed to place them. I even knew the title! I wanted to show how the events of 9/11 affected everyone, across the entire county. I didn’t want to limit my story to New York City or to the day of the attacks. That is another story, another book, for another writer to tell.

For my story, I deliberately chose characters spanning from California to New York, rural to urban, black to white, boy to girl, Jewish to Muslim to Christian. I wanted to make them as different as I could to reveal how similar they actually are—how similar WE actually are—and to show how this tragedy connected us all in ways both big and small.

Of course I wanted to, and I could have tried to include more, but it is already a challenge for young readers (and writers!) to keep track of multiple characters. So I kept it to four. And since setting in a story also refers to time, my book begins 48 hours before September 11, 2001. I wanted to draw a line between the before and the after and show how the world changed that day.

First there is Will, a boy living in Shanksville, PA, the town where the fourth plane crashed after being diverted from its target (The Capitol building) because of the incredible heroism of the passengers on Flight 93.

I also wrote about Sergio, a boy in Brooklyn, who that morning witnessed the Twin Towers collapsing in a mushroom cloud of black smoke and white ash. He has a friend and mentor who is an EMT, who I chose because I knew I could not address the events of 9/11 without honoring the bravery of the first responders, many of whom died that day and in the days and years that followed.

I brought Aimee to life in California. Her mother had a meeting at the World Trade Center that morning and narrowly escaped death. I needed to speak about the beauty of life and how we sometimes, sadly, only fully realize that when it is almost lost.

And lastly, there's Naheed, an Iranian Muslim girl in Columbus, Ohio, whom I very consciously gave a Persian ancestry in order to point out a specific kind of bigotry. Not all Muslims are Arab; not all Arabs are Muslims; and not all Middle Easterners are Arab or Muslim or Jewish. As we know, after 9/11 the rise of Islamophobia and xenophobia exploded and was often directed blindly at anyone of Middle Eastern descent. I needed to show how the fear of terrorism generated an increase in this discrimination, an anger that was spewed widely and with ignorance.

In my small way, I wanted to help young readers open their eyes and their minds. I wanted them to learn about a time in our history that many adults felt was too hard, too scary, too sad to talk about. Reading can bring empathy, understanding, and knowledge—at least that was my hope.

I've long struggled with the moments that cleave our lives into a before and an after, and there seems to be few modern shared before and afters quite like 9/11. Although there are a gazillion political ramifications from that day, I tend to be more interested in the personal legacies of loss. How they shape us. How we continue to live despite knowing that the world can cleave at any time. How we risk loving and losing. How we laugh in spite of it all.

Baby Hope, an entirely fictional character and photo, became the long lens that allowed me to look more deeply at those questions. She also allowed me to explore the myriad ways 9/11 still isn't over. As many as four hundred thousand people are still struggling with health conditions related to that terrible day. By framing my story with a modern teenage girl, I hoped to introduce the legacy of 9/11 to the generation born since 2001, for whom the event feels like ancient history. Unfortunately, it is not.

3. Twenty years after the events of September 11, 2001, how might you change or add to your story?

In the span of the seventeen years since my novel, Refugees was published, and a full twenty years since 9/11, life for Afghans has improved dramatically, and yet this fascinating country is also stubbornly resistant to change for reasons that I was able to profile in the book. It may have a centralized government on paper, but its localized, tribal structure holds firm. Its poppy trade is almost impossible to eradicate, as it is a huge money source, which keeps the Taliban in power. It seems likely that the Afghan army will still buckle under the Taliban. This will also set women’s rights back, but hopefully, they will not lose all hard-fought ground. Pakistan’s badgering influence still holds. There’s the infernal question of whether the USA should be a peacekeeping force to the world, or whether it’s really time to pack up and leave. These questions have no easy answers.

My intention with Refugees, was to present, through the personal lens of Johar, an Afghan boy and Bija, his little cousin, the day-to-day life, and the danger after 9/11 that also existed for those in Afghanistan. My extensive research taught me about their ancient culture, the intricacies of their tribal networks, and the stark beauty of the people. This information is relevant after all this time. Perhaps if I changed anything, it would be to hint that this was a snapshot in time, and that history often has circular cycles.

I'm glad I wrote The Memory of Things when I did versus now as it would definitely have to be more political— and more divided—now. I'm always hoping young readers will see how, at that time, in the face of tragedy, we found our shared humanity much more readily and rallied together, human to human, without regard for politics.

Of course, that was on a whole, but there were splinters of misinformation and hate that arose from the event as well, and were, in fact, the spark of one form of ongoing hate in our country, and our stories deal with that . . . in The Memory of Things in particular, a moving moment when the kids head out of the subway on Stillwell Avenue on their way to Coney Island in the days after and pass heavily gated stores bearing Arabic names and signs that plead for us all to remember that they, too, are "[f]irst Americans." That was based on a sign I saw in a photograph during the research phase of my book, and if there's one thing readers take from my story after a simple sense of hope, it is that: our shared humanity.

The 20 Novels

* * *

The events of 9/11 are challenging to describe and discuss, especially with children who were not yet born, which at this point is most of our student population. I think that is so because, as adults, we each have our memories of that day and Life Before. I was a middle school teacher on the day the Towers fell. I remember standing in my classroom as our team teachers watched the morning news. Thankfully, our students were in their Specials and were not witness to the shock and tears on our faces. I don’t remember much of that day, but we were located in Philadelphia and did not immediately feel the effects. But the events o that day have affected our country and all our citizens as well as our contemporary world. The importance of studying and discussing 9/11 as part of American history is highlighted in Jewell Parker Rhoads novel Towers Falling, set in September, 2016.

Nine Ten: A September 11 Story is another novel effective in introducing young adolescent students to the many events of September 11, 2001. Nora Raleigh Baskin’s novel is set during the days leading up to 9/11—in Brooklyn, Los Angeles, Columbus, and Shanksvlle, Pennsylvania, where readers follow four diverse middle-grade students affected by the events of 9/11. Sergio, Naheed, Aimee, and Will first cross paths in the O’Hare Airport on September 9. The four young adolescents are Black, White, Jewish, and Muslim and are collectively surviving loss, guilt, poverty, parental absence, neglectful fathers, bullying, the navigation of peer relationships, as well as the angst of middle school, “…everything felt different, as if you suddenly realized you had been coming to school in your pajamas and you had to figure out a way to hide this fact before anyone else noticed.” (p. 48). In their own ways they are each affected by 9/11, and on September 11, 2002, these four and their families again converge at Ground Zero, each there for different reasons, but this time their paths back together have meaning.

There are a multitude of important conversations to be generated by this little novel, a story of Before and After. I was especially grateful that the events and heroes of Shanksville were memorialized. In fact there are many aspects of heroism brought forth in the novel to discuss. But Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story is the story of people and three days in their lives, “Because in the end it was just about people…Because the world changed that day, slowly and then all at once.” (p. 176).

“We don’t trust anymore, and that’s the saddest thing of all.’” (116)

Eve Bunting’s chapter book is not about the events of September 11, 2001, but it is about the effects and repercussions that we are still experiencing from 9/11.

Kevin Saunders and his grandmother go on a bus trip out West and immediately notice a fellow traveler, Charles Stavros, a man who says he is Greek but raised in America. A man who Kevin thinks looks like “…he might be Saudi Arabian or even Iraqian, if there is such a word. He was dark skinned, with bushy black eyebrows and a bushier mustache.” (2) And a man who constantly carries a red bag which he refuses to put down, even on a rafting trip.

Some of the other passengers worry that he is a terrorist and that his face looks familiar. As Kevin’s Grandma says, “It’s sad. People are quick to jump to conclusions now. If someone looks like that—” (10)

Kevin, a voracious reader of Joan Lowery Nixon mystery novels and his “much-read how-to-write-a-mystery book and is convinced that Stavros is a terrorist, is anxious to solve the mystery of the red bag which he is sure is holding a bomb. His elicits the help of the other young passenger, Geneva, who also wants to be a hero and appear on the Oprah show. Geneva’s eyes opened wide. ‘He does look exactly like a terrorist. I’ve never seen a real one, but I’ve seen pictures on TV.’” (39)

As they follow Stavros, even keeping watch on his various hotel rooms all night, they become more and more convinced that he is going to bomb an American monument, possibly Mount Rushmore, and that they can save the day. And then Kevin can write the mystery. “I didn’t want him to be Greek. I didn’t want him to be innocent. I didn’t want to lose my big mystery adventure. But just think how scary it would be if he wasn’t Greek. If he was something else! Having a mystery also meant having a terrorist aboard. And a bomb. Criminy! What did I want?” (60)

What they find ties Stavros to 9/11, but not in the way they think.

This is yet another perspective of the events and effects of September 11, 2001, appropriate for grade 4-8 readers.

For many people the world is divided into Before and After, the dividing line being September 11, 2001. Such is the case for Abbi Hope Goldstein and Noah Stern.

On her first birthday Abbi was saved by a worker in her World Trade Center complex daycare center. As she is carried out, wearing a crown and holding a red balloon, the South Tower collapsing behind, a photographer takes the picture that has branded her Baby Hope, the symbol of resilience. Abbi spends her childhood and adolescence in relative fame; strangers hug and cry, share their stories with her, frame and hang the photograph in their homes, and news outlets hold “Where is Baby Hope Now” stories.

Noah was a baby in the hospital, fighting for his life, on 9/11 when his father went back to his office in the World Trade Center for his lucky hat, never to return home. He and his mother now live with her new husband and Noah is obsessed with comedy.

At age 15, Abbi is experiencing a suspicious cough, keeping it a secret from her parents and grandmother. Connie, the daycare worker, has recently died from cancer, most likely 9/11 syndrome, and Abbi takes a job as a camp counselor in a nearby town, looking for some anonymity and a chance at a “happily ever after” to the story that began with “Once upon a time” (9/11). Unfortunately, Noah, a fellow counselor, recognizes her and blackmails her into helping him interview the four other people in the iconic Baby Hope picture, convinced that the man in background wearing a Michigan cap is his father and also convinced, since his mother won’t talk about him, that his father chose not to come home after escaping from the Tower.

This is a novel about 9/11, one that presents yet more facets than many other 9/11 novels, such as 9/11 syndrome which is affecting many of those who were at Ground Zero, heroism and sacrifice, survivor guilt, and “[What] happens when the story you tell yourself turns out not to be your story at all.” (280)

This is primarily a novel about relationships—shifting relationships with family, friends, ex-friends, strangers, and romantic partners. I absolutely adored these characters—Noah and Abbi especially (and their evolving relationship) and Noah’s BFF Jack, Abbi’s divorced-but-best-friends-and-maybe-more parents, her grandmother who is experiencing the onset of dementia, and even Noah’s stepfather who learns to make jokes. I was sorry when the novel ended, not that the story was unfinished but my relationship with the characters was.

Relationships are built over time, but how much can they withstand? Jake Green and Sameed Madina have always been friends. They have grown up together; they run track together; they play war games together; they have each other backs; they plan to always remain friends “but only till Martians invade the earth.”

But then the events of September 11, 2001, occurred, and Martians did invade the earth, only they looked like Sam and his family—Muslim. Because one of the terrorists had lived in their neighborhood and was a client at the bank where Mr. Madina worked, Sam’s father comes under FBI surveillance, and the neighborhood divides in their support. Not Jake, though. He believes in his friend and his friend’s family, physically fighting the school bully who refers to Sam as a “towelhead” and arguing with his own mother whose own grief keeps her from supporting their neighbors.

When his father is taken into custody, Sam refuses to attend school, abandons his cross-country team, and distances himself from Jake, taking a new interest in the Islam religion. But Jake does not give up, and the boys reconnect to peacefully stop their racist classmates, Bobby and Rigo, from attacking the local mosque. Afterwards, Jake realizes that they both have been affected by 9/11; he has learned that you can be both scared and brave at the same time, but he has also has learned that adversity can be defeated peacefully. And Jake realizes that Sam is now different. “For the first time I see Sam, a Muslim. An American Muslim. But he is still just Sam, no matter what.”

Ema is binational, bicultural, bilingual, and biracial. Some people consider her “half,” and others consider her “double.” Her American mother says she contains “multitudes,” but Ema sometimes feels alone living in Japan somewhere among multitudes of people.

When fifth-grader Ema and her mother go to live with Ema’s very traditional Japanese grandparents during a difficult pregnancy, author Annie Donwerth-Chikamatsu’s verse novel takes the reader through six months (June 21, 2001-January 2, 2002) of customs, rituals, and holidays, both Japanese and American. There are challenges, such a choosing a name for the new baby that brings good luck in Japan and that both sets of grandparents can pronounce. Ema celebrates American Independence Day and Japanese Sea Day, and she now views some days, such as August 15 Victory Over Japan Day from diverse perspectives.

On September 11, 2001 Ema experiences both two typhoons in her town and the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in America—on television. As the reader traverses the intricacies of two fusing two distinct cultures with Emi and her family, our knowledge of others is doubled.

2001:

“the year we moved to Tennessee,

the year of the terrorist attacks,

the year my period arrived,

the year Aunt Rose died,

and the year Dad left for Afghanistan.” (166)

Twelve year old Abbey is, as the boys in her new school call her, an Army brat. She has moved eight times, but this time she is not living on base with others like her. This time she attends a school where there is only one other new girl, Jiman, a Muslim-American of Kurdish heritage, born and raised in New Jersey.

Abbey is shy, uncertain, voiceless,

“I worry about people speaking to me

And worry just the same

When they don’t.” (27)

“Here’s what I’m used to being:

the last to be picked,

that girl over there,

the one hiding behind her hair

counted absent when present,

the one who eats alone,

sits alone,

the quiet type,

a sit-on-the-sidelines type,

the girl who draws,

and lately

‘Army brat.’” (107-8)

Luckily over the summer before school began, she made a new best friend, Camille, who is athletic and confident and has no trouble standing up to bullying.

As Abbey deals with her new school and the taunts of the other 7th graders and the boys on the school bus, the Twin Towers are hit and Abbey’s Aunt Rose is missing from her office on the 86th floor of the World Trade Center.

“Was she aware,

Unaware,

Have time to prepare…

Have time to think, to blink,

Time to wish, to wonder,

Did someone help her,

Was she alone,

Did she whisper a prayer,…” (24)

During this year Abbey contends with her periods, her missing aunt, her mother’s temporary absence to New York to take care of Aunt Rose’s husband and children, the “Trio” of Henley Middle ( the popular Mean girls), the eventual deployment of her father, and, on a positive note, the attentions of Jacob—Camille’s other best friend. Abbey also notices how people are treating Jiman who remains confident, appears comfortable alone, and stands up when her little brother is harassed, but has no one championing her. At times Abbey feels she should speak up on behalf of Jiman, but she continues to keep quiet, losing herself in her art.

“What I don’t do

is tell them to shut up,

to leave people alone for once

because mostly I’m relieved

that they’ve forgotten

about me. “(120)

Through art, Abbey finally gets to know Jiman and gains strength from her, strength to become an upstander rather than a bystander. With Camille, Jacob, and Jiman as friends, Abbey realizes,

“Sometimes it takes an eternity to figure things out,

Especially when you’re in middle school.” (245)

Caroline Brooks DuBois’ debut novel written in free verse and formatted creatively on the pages is a coming-of-age novel, a novel of fitting in, gaining confidence, showing tolerance and kindness towards others and standing up—for oneself and others.

Two children 18 years apart, both at the mercy of terrorists, both in death-defying situations, both fighting for their lives, and both showing courage and compassion for others as they live with grief. At one point they are both at their own Ground Zero.

Nine-year-old Brandon goes to work with his father at the Windows on the World restaurant on the 107th floor of the North Tower. The date is September 11, 2001. He leaves his father to go down to the Mall to buy something for a friend, and while he is descending in an elevator, the first plane hits the Tower. As Brandon tries to make his way up to his dad and then, when that is impossible, back down to fulfill his father’s wishes, “Brandon, hang up [the phone] and get out of the building as fast as you can.” (158) and “You’re strong. You can survive without me.” (234), he meets Richard who takes him under his wing. “It didn’t feel weird at all to Brandon to be clinging to a stranger right now. It was reassuring to connect with someone else who was sharing the struggle to survive.” (104) Together, on the way down, Brandon witnesses every horror—elevators filled with people crashing, workers falling and jumping out of the building to their deaths, people catching on fire—but the people he and Richard meet collaborate to help each other until finally Brandon makes it to safety and is able to save Richard when the Tower collapses.

Meanwhile on September 11, 2019, Reshmina, an 11-year-old Afghani, lives with her family in a small village in the middle of constant fighting between the Americans and the Afghan National Army and the Taliban. Her sister had been accidentally killed by American soldiers on Hila’s wedding day “We’re fighting a war again the Taliban. Sometimes innocent people get hurt.” (246). When an American soldier is hurt, with conflicting emotions, Reshmina hides him in her house, she puts her family and her village in grave danger. Her resentful twin Pasoon leaves home to join the Taliban and to tell them about the soldier. In danger Reshmina and her family leave to hide in a cave. “She had chosen what was right over what was easy. She had dared to be someone new, someone better, to carve a path for herself. And look where it had gotten her; buried with her family in a grave of her own making.” (245) After Reshmina’s ingenuity helps her family and the villagers to successfully escape the collapsed cave, the American soldiers sweep in to rescue Taz and order a strike against the Taliban. Again accidently, the houses in the village are all wiped out. “When they were all safe, they all turned and watched as the village slid down into nothing, swallowed by the great brown cloud of dust that came roaring at them like a lion.” (282) “‘That was not supposed to happen.’ ‘And yet it did,’ Reshmina said.” (283)

When Brandon’s and Reshmina’s stories converge, readers learn just how complicated is the present American military involvement in Afghanistan and the ongoing impact of revenge.

“…even if I felt something was wrong, I would never have pictured this. This isn’t even something I’ve feared, because I never knew it was a possibility/” (5) “’We are not supposed to comprehend something like this,’ my mother says to me…. I don’t want to comprehend. Instead, I will try to remember what matters.” (16)

The attacks of September 11, 2001, affected our country as a whole, but it is even harder to imagine the effect on those who lived in NYC. Claire, Peter, and Jasper are three teenagers living in NYC on that date. Claire leaves her high school to pick up her brother from his elementary school; Peter has already left school and is at the record store, thinking about his impending date with Jasper; and Jasper is at home alone, his parents visiting their native Korea, before he leaves for college. None of the three are directly affected—none of their parents worked in the World Trade Center, none of their friends or relatives were killed; they were not physically hurt—but the events of this day color the year following. “I want to know why this is so much a part of me. I want to know why this thing that happened to other people has happened so much to me.” (104)

Readers view the day through their alternating perspectives. We view the constructive acts of strangers as Claire observes, “There are skyscrapers collapsing behind us, and nobody is pushing, nobody is yelling. When people see we’re a school group, they’re careful not to separate us. Stores are not only giving away sneakers, but some are handing out water to people who need it. You’d think they’d take advantage and raise the prices. But no. That’s not what happens.” (14) and Peter reflects, “And the people I care about, suddenly I care about them a little more, in this existential way.” (82)

Even though Peter and Jason’s date does not go well, another ramification of the day, the three become friends, especially Claire and Peter who attend high school together, Jason returning to college. And the year continues, each is a little changed. As Peter observes, “ If you start the day reading the obituaries, you live your day a little differently.” (123)

By December Jasper observes that he has finally gone an entire day without thinking of 9/11 but then wonders what that means. Claire feels the weight of the day lighten a little, but “It is still strange to see the skyline. I have never seen an absence that it so physical.” (126)

On the anniversary of 9/11 Claire retraces the steps she took on that day, and Peter and Jason finally have a second date. On March 19, 2003, the day of the United States invasion of Iraq, the three reunite, and Claire observes, “And we are so different from who we were on September 10th. And also different from who we were on the 11th. And the 12th. And yesterday.” (163) Together they have found the “antidote” to the fear and uncertainty; they have each other as they individually navigate the world and remember what matters.

“The bigger the issue, the smaller you write.”--Richard Price

Instead of focusing on the overwhelming statistics generated by the March 11, 2011 earthquake and resulting tsunami in Japan—nearly 16,000 deaths and 3,000 people missing—the event becomes even more intense and compelling as author Leza Lowitz relates the story of one town and one boy and the resilience of many.

The story begins on March 11 when Kai, a half Japanese, half American 17-year-old and his teachers and classmates experience the “jolting of the earth,” and as trained, they evacuate, running for their lives, looking for the highest place, as their town is destroyed. Written powerfully in free verse, the reader feels the fury of nature as the water “churns,” “thrashes,” “surges,” “sweeps,” “charges.” Kai ends up in a shelter having lost his mother, his grandparents, and one of his best friends. His father left years before to return to America.

Faced with overwhelming loss and trauma, Kai walks into the ocean but is saved by one of his classmates and convinced to accept the opportunity to go to New York City on the tenth anniversary of 9/11 where he will spend some time with young adults who lost their parents as teens in the 9/11 attacks. At Ground Zero, Fia tells him, “Bravery means being scared and going forward anyway.”

Kai hopes to find his father in NYC but returns to his village to help the young adolescents who lost their families and to rebuild his town. “I want to be/ like that tree/ deep roots/ making it strong/ keeping it/ standing tall.” And it is to his roots Kai returns and stays—“The quake moved the earth/ ten inches/ on its axis./ I guess/I shifted,” too.”

Up from the Sea, well-written as a verse novel (a format that engages many reluctant readers), would serve as an effective continuation to a 9/11 study. Readers should already be aware of the events of 9/11 to understand the connection between Kai and Tom but will comprehend the trauma and loss experienced, and resilience that is required, by anyone who faces adversity.

The Usual Rules is an emotional and insightful novel about the effects of the events of September 11th on the families and friends of the victims—those left behind.

The reader learns about the close relationship between 13-year-old Wendy and her mother through flashbacks: her mother's divorce, the sporadic visits of her father, her mother's marriage to her "other dad," and the birth of her half-brother. And then her mother goes to work at her job at the World Trade Center on 9/11/2001—and does not return. Wendy’s world changes. “Then September happened and the planet she lived on had seemed more like a meteor, spinning and falling” (p. 175).

The reader experiences not only Wendy's (and Josh's and Louie's) loss but the suffering and uncertainty of those left behind. Could her mother be walking around, not remembering who she is? As the family hangs signs, we learn how different this loss was for many people who held out hope for a long time without a sense of closure. And this loss was different because it was experienced by many—an entire country in a way. “Instead of just dealing with your own heart getting ripped into pieces, wherever you looked you knew there were other people dealing with the same thing. You couldn’t even be alone with it” (p. 95).

We see the loss through the eyes and hearts of a daughter, a very young son, and a desperately-in-love husband. Wendy leaves Brooklyn and goes to her biological father’s in California. Among strangers, she re-invents her life. As those she meets help fill the hole in her life, she fills the hole in theirs. Books also help her to heal.

Even though there are quite a few characters in this novel, but they all are well-developed, and I found myself becoming involved in all their lives, not only Wendy, Josh, and Louie and even his father Garrett, but Wendy’s new friends—Carolyn, Alan, Todd, Violet… On some level they all have experienced trauma and loss, and within these relationships, Wendy is able to heal and return to rebuild her family.

Although I did not want this novel to end and to leave these characters, this well-written novel taught me more about the effects of September 11, loss, and the importance of relationships and added a new perspective to my collection of 9/11 novels.

September 11. A day that changed all our lives in some way. As we see in Nine, Ten: A September 21 Story, there clearly was a Before and After. But there also was a Then or That Day and an After.

All We Have Left was so compelling that I read from dawn to dusk and did not put the book down until I finished. The novel intertwines two stories, that of 18-year-old Travis and sixteen-year-old Alia who were in the Towers as they fell and the story of Travis’ sister, Jesse, who, fifteen years later, is part of a dysfunctional family whose lives are still overwhelmingly affected by That Day and Travis’ death.

Seventeen year old Jesse is not sure who she is, who she should be, who she should hate, and who she can love. Her life is overshadowed by 9/11, her mother’s mourning, and her father’s hate.

But both Alia in 2001, and Jesse in 2016, learn that “Faith and strength aren’t something that you wear like some sort of costume; they come from inside you” (p.329) as does love. And Jesse realizes that she has to work on “treasuring right here, right now, because that’s important.” As one character says but all the characters learn, “You can fill that void inside you with anger, or you can fill it with the love for the ones who remain beside you, with hope for the future.”

What I appreciated about this novel is that is shows yet another side of how 9/11 affected people, especially adolescents, those adolescents who populate American schools everywhere. I strongly feel that students should not only be learning about the events and effects of 9/11, but that, through novels, readers learn more about how events affect people and especially children their ages.

Another novel as a complement to a 9/11 Novel Study would be Maria Padian’s novel about the ways life in an idyllic small Maine town quickly gets turned upside down after the events of 9/11.

“Things get a little more complicated when you know somebody’s story.…It’s hard to fear someone, or be cruel to them, when you know their story.”

The majority of the 21.3 million refugees worldwide in 2016 were from Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia. The United States resettled 84,994 refugees. Together with immigrants, refugee children make up one in five children in the U.S. More than half the Syrian refugees who were resettled in the U.S. between October 2010 and November 2015 are under the age of 20.

.

In Out of Nowhere narrator Tom Bouchard is a high school senior. He is a soccer player, top of his class academically, and well-liked. He lives in Maine in a town that has become a secondary migration location for Somali refugees. These Somali students are trying to navigate high school without many benefits, including the English language. They face hostility from many of their fellow classmates and the townspeople, including the mayor; one teacher, at the request of students, permits only English to be spoken in her classroom.

When four Somali boys join the soccer team, turning it into a winning team, and when he is forced to complete volunteer hours at the K Street Center where he tutors a young Somali boy and works with a female Somali classmate, Tom learns at least a part of their stories. Tom fights bigotry, especially that of his girlfriend—now ex-girlfriend, but he still doesn’t comprehend the complexity of the beliefs, customs, and traditions of his new friends, and his actions have negative consequences for all involved. While trying to defend the truth, Tom learns a valuable lesson, “Truth is a difficult word. One person’s truth is another person’s falsehood. People believe what appears to be true and what they feel is true.”

The first 9/11 novel I read, The Memory of Things is lovely story about the effects of the events of 9/11. Another reason we read is to understand events we have not experienced and the effect of those events on others who may be like ourselves. After witnessing the fall of the first Twin Towers on 9-11 and evacuating his school, teenager Kyle Donahue, a student at Stuyvesant High School, discovers a girl who is covered in ash on the Brooklyn Bridge; she has no memory of who she is. The son of a detective, he takes her home to help her rediscover who she is, why she was where she was, what she was doing there, and her connection to the events.

Author Gae Polisner wrote The Memory of Things in alternating narratives—Kyle's in prose, the girl writes in free verse—the two characters sharing their stories and perspectives, introducing adolescent readers, many of whom had were not alive during 9/11, to the effects of this tragedy in their own ways.

I was a middle-school teacher in 2001. It was challenging to know how to discuss the events of 9/11 as we lived through them. How is a teacher to meaningfully discuss this momentous event with students who were not even born in 2001? Falling Towers is a thoughtful, provocative, well-written, albeit emotional, novel about this topic written sensitively and appropriately for readers as young as Grade 4, an ideal novel for middle grades Social Studies classes as it focuses on not only the history of 9/11 and its place in American history but the ever-widening circles of relationships among, and connections between, Americans beginning with families, friends, schools, communities, cities, states, countries.

The 5th grade characters explore “What does it mean to be an American?” as well as why history is relevant, alive, and, especially, personal as three students—one Black, one White, one Muslim—explore the effects of the events of 9/11 on each of their families. Déja’s “journey of discovery” about the falling of the Towers helps her father work through his connection to the event and his resulting PTSD.

“After today, everything’s changed.”

“Sometimes when a terrible thing happens, it can make a beautiful thing seem even more precious.”

Eleven is the story of Alex who is turning 11 on September 11, 2001. I was concerned that the character would be too young for this topic. I also thought that, the character age’s implied that the novel wouldn’t contain the complexity the topic deserves. but, boy, was I wrong! I was hooked with the complexity of the first 2-page chapter. I wasn’t sure what was happening in this introductory chapter, but it was not a feeling of confusion as much as “It could be this; no, it could be this…” and inference and interpretation, even visualization.

I also forgot that New York City kids grow up faster, taking public transportation throughout the city, but more importantly, I forgot that when you need or expect a young adolescent to rise to the occasion, he will.

Alex loves airplanes and dogs—and he doesn’t realize it, but he loves his little sister Nunu who is relegated to her side of the bedroom they share by a black and yellow “flight line” down the middle of the room. And he loves his father, even though Alex told him, “I hate you,” the night before 9/11. When the Towers fall, Alex rises to the occasion, taking care of his little sister and an abandoned dog, making the sacrifice to return the dog he has always wanted to his owners when the vet finds a chip, facing bullies, making “deals” in the hopes these deals and good works will offset what he said to his father and ascertain his return from the Towers, and comforting Mac, a lonely man who is awaiting his only son’s return from the Towers.

In Eleven author Tom Rogers builds a character who is authentic, a kid who events serve to turn into a young man. Alex’s mother had said to him, “I need you to be grown up today” and, even though he was focusing on his misdeeds of the day, he did. “I’m proud of you, young man…. Young Man. Alex liked how that sounded.”

This book is not graphic but does not skirt the events. Readers hear the news announcement about the four airplanes and, more chilling, a description of an empty hospital—“There were no gurneys rolling through to the ER, no sick and wounded in pain. There wasn’t a patient in sight. And he knew then that none would be coming.” A powerful examination of the events of 9/11 and how they affected ordinary people—and one boy’s birthday.

Refugees adds another dimension to the 9/11 novels.

Dawn is a foster teen who runs away to New York City and becomes affected by the events of 9/11. As she plays her flute on the streets near Ground Zero to earn money for food, she is approached by families of victims who ask her to play for them and the memories of their loved ones. As Dawn comes to believe this is her mission, she teaches herself music she feels appropriate for those of many cultures and stages of life. In doing so, she opens up to strangers and new friends, something she couldn't do with her foster mother.

Johar is an Afghani teenager, weaver, and poet. His father is killed by the Taliban, his mother is killed by a land mine, his older brother joins the Taliban, and his aunt is missing, leaving Johar to care for his three-year-old cousin. He and his cousin flee to a refugee camp in Pakistan where he works for the Red Cross doctor, Dawn's foster mother, another person who must learn to show love.

Dawn and Johar connect through phone calls and emails, and as they all work toward forming a family—one that spans the globe—the reader learns how war, the U.S. involvement, and the events of 9/11 affected those in many countries. This would be a book I would recommend for proficient readers with an interest in war or history.

P.S. After I read this book and posted my original Goodreads review, I was listening to a discussion about the days following 9/11 in the Middle East on NPR and found that I could actually follow it; therefore, I realize that I learned more than I thought from this novel.

I SURVIVED The Attacks of September 11, 2001 is now available as a graphic novel re-adaptation of Lauren Tarshis' 2012 novel, written by Tarshis and illustrated by Corey Egbert.

“A bright blue sky stretched over New York City.” That is what many of us who were alive on September 21, 2001, remember—the cloudless blue sky of northeastern United States—the contrast between the perfect day and the day which has changed our world.

As the son of a firefighter, Lucas was aware of the effects of danger and disasters. His father had been severely injured in a warehouse fire and was still not himself (“It turned him quiet.”). It had been a while since they had worked together on the firetruck model in the basement. But it was another tragedy that brought them back together as a family.

Lucas had sneaked into NYC that September 11 morning to ask his uncle to intercede on his behalf. After three concussions in two years of football, his parents and doctor were taking him off the team, and Lucas loved being on a team, a team of two with his father, his dad and uncle’s Ladder 177 firehouse, and especially his football team. Lucas was near Ground Zero when the planes hit the Towers, and when his father went looking for him, they were able to make it safely back to the fire station, helping others along the way.

Readers view the attacks of 9/11 up close and personal through Lucas’ eyes; they experience his loss, the heroism of the firefighters, and the resilience of his father. We feel the dust of the falling Towers, see the sky fogged with dust and ashes. “It wasn’t like regular dust. Some of the grains were jagged—bits of ground glass.… The dust, Lucas realized. That was the tower. It was practically all that was left.”

The story ends on a realistic but positive note with Lucas, not a player, but still a valued member of the football team. “Nothing would ever be the same again.” But his father told him, as time passed, it would get, not easy, but easier.

This was the first book in Tarshis’ I Survived series that I have read, and I was impressed with the writing, development of the main character, and the complexity of ideas presented in such a short text. This novel could be employed for MG or YA readers who are less proficient or more reluctant readers; English Language Learners who may not be ready for a longer or more complicated text; students who are short on time through absences, trips, or other obligations or who joined the class during the unit; or as a quick whole-class read for background before students break into book clubs to read one of the other 9/11 novels.

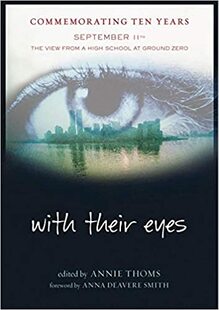

“Journalism itself is, as we know, history’s first draft.” (xiii)

With Their Eyes was written from not only a unique perspective—those who watched the attack on the World Trade Center and the fall of the towers from their vantage point at Stuyvesant High School, a mere four blocks from Ground Zero, but in a unique format. Inspired by the work of Anna Deavere Smith whose work combines interviews of subjects with performance to interpret their words, English teacher Annie Thoms led one student director, two student producers, and ten student cast members in the creation—the writing and performance—of this play.

The students interviewed members of the Stuyvesant High study body, faculty, administration, and staff and turned their stories of the historic day and the days that followed into poem-monologues. They transcribed and edited these interviews, keeping close to the interviewees’ words and speech patterns because “each individual has a particular story to tell and the story is more than words: the story is its rhythms and its breaths.” (xiv) They next rehearsed the monologues, each actor playing a variety of roles. Although cast members were chosen from all four grades and to represent the school’s diversity, actors did not necessarily match the culture of their interviewees.

They next planned the order of the stories to speak to each other, “paint a picture of anger and panic, of hope and strength, of humor and resilience” (7), rehearsed, and presented two performances in February 2002.

With Their Eyes presents the stories of those affected by the events of 9/11 in diverse ways. It shares the stories of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors, special education students, an English teacher, a Social Studies teacher, the School Safety Agent, the Building Coordinator, a dining hall worker, a custodian, an assistant principal, and more, some male, some female, some named, others remain anonymous. Written as a play, readers are given a description of each character. Read and performed as a play, readers will experience the effect of Nine Eleven on others, actual people who lived that day and persisted in those days that followed, sharing their big moments and little thoughts.

“the air felt on the outside like something that you might smell at a,

or feel at a barbecue,

but it didn’t, it…it hurt you.

It hurt your windpipe.

I could feel like, things collecting on my esophagus or on my lungs,

and I don’t think that is something that I will ever forget.” (44)

--------

“and you know

what an odd thing this is

a peculiar little odd thing

just a little quirk, just

an odd thing, but, ah, the day before

on Monday evening I had taken the time to shine my shoes.

‘cause it’s kind of weird I took the time to shine my shoes

and I did a good job, right,

and then Tuesday morning

it was a beautiful sunny day

you know

and as I was dusting myself off

from the debris of the north tower

I—I shook my clothes off and then I looked down

at my shoes and my shoes were a whole ‘nother color

they were completely covered

and I thought to myself

‘I just shined them yesterday’…” (102)

--------

And the pregnant English teacher who said,

“…during that time of feeling afraid I felt like I was

crazy to be in New York…

and I had lots of conversations with my friends about

whether or not we would…

we would consider, you know, just completely changing our

lives and leaving New York

So far I don’t know anyone who has done that.

But do I plan to raise my child in New York? Yes.” (90)

You know, I really believe in healing

And I believe that, the city will

um… be

healed.

I think you have to believe that.” (93)

With Their Eyes was written with the thoughts and pens of a school community.

“The sky was so blue, without the trace of a single cloud, that it looked like a postcard. It felt more like a summer day than a September day. It was a nice day not to be in school. Then again, being in my father’s office wouldn’t be that much different or better. (36)

The day was September 11, 2001, a teacher meeting day during which students at Will’s high school were to shadow their parents at their workplaces. Ninth-grader William’s father John worked in international trade in the World Trade Center.

Upon arrival, father and son went to the 107th floor Observation Deck for a quick tour and history of the Center and view of the city. “Maybe my father was right and the World Trade Center and all the money that passed through here each day really did represent the United States.” (42)

At 8:46, shortly after arriving at John’s office on the 85th floor of the South Tower, they felt the force of an explosion. And as he looked out the window Will saw a gaping hole in the North Tower, billowing smoke, thousands of pieces of paper—some on fire—and, before he could look away, he was horrified to notice a man and woman jumping from windows of the building.

Will’s father, as acting head of his office and fire warden for the floor, demanded that his staff and other businesses on the floor close and evacuate for the day. But at 9:03, just before John and Will were able to leave, the second plane hit the South Tower.

Readers follow the father and son as they make the harrowing journey down 85 floors through heat and smoke, formulating split-second decisions and stopping to rescue and carry an injured woman, only to experience the collapse of the building as they reach the lobby.

A quick but dramatic read, Eric Walters’ novel lets readers experience a close-up account of the day and the panic and fear and heroism of ordinary people—John and Will, the men carrying a man in a wheelchair, the firemen and police—as Will discovers another side of his father and John realizes how much time he has devoted to his job rather than to his family.

The title derives from the children’s rhyme “Ring Around the Rosie,” a song that is actually about the Black Death during the Dark Ages. Will learns this in history class on the previous school day, a foreshadowing of events to occur.

The sequel to We All Fall Down begins on September 12, 2001 when Will’s best friend’s father, a firefighter at Ground Zero, last seen as he climbed the steps of the North Tower, is missing.

“After September eleventh, I never felt more un-American in my whole life, yet at the same time, I felt the most American I’ve ever felt too. I never knew it, but this has been a recurring theme throughout my life and it seemed to get shoved into my face after the attacks on the World Trade Center.” (150-151)

Samar Ahluwahlia is an Indian-American teen living in Linton, NJ, with her mother who turned her back on her family and religion. When the events of September 11th occurred, shaking Sam as well as her classmates and community, she didn’t realize that those events would affect her personally. Until her Uncle Sandeep appeared on their doorstep.

“Before Uncle Sandeep walked back into my life, I’d never cared that I was a Sikh. It really didn’t have much impact on my life,…. But that was before 9/11. The Saturday morning that Uncle Sandeep rang our doorbell had one of those endless, frozen blue skies hanging above it; the same kind of frozen blue sky that, just four days earlier, had born silent witness to a burning Pentagon and two crumbling mighty towers in New York City. And the cause of all those lost lives was linked to another bearded, turbaned man halfway around the world. And my regular, sort of popular, happily assimilated Indian-American butt got rammed real hard into the cold seat of reality.” (10)

After becoming re-acquainted with her personable, loveable and loving, optimistic uncle, visiting his gurdwara (temple), and watching the harassment and hate aimed against him even though he is Indian, American, and Sikh, rather than the Middle Eastern and Muslim, Sammy decides she wants to learn more about Sikhism and meet her family, hoping to have what her best friend Molly has with her large Irish family. “This discovering more about myself stuff is addictive. It’s like starting a book that you just can’t out down, only it’s better because the whole book is about you.” (110)

After being termed a “coconut” by an Indian girl at school and learning about the WWII Japanese internment camps, Sam begins researching intolerance, joins a Sikh teen chat group, and convinces her mother to take her to visit her grandparents where she is exposed to the traditional “values” that caused her mother to rebel.

However, when Molly includes their childhood enemy Bobbi Lewis in their friendship and Sam finally acknowledges that the supportive Bobbi has changed or maybe isn’t whom she thought, Sam realizes, “If we give them a chance, people could surprise us. Maybe if we didn’t make up our minds right away, based on a few familiar clues, we’d leave room for people to show us a bunch of little, important layers that we never would have expected to see.” (149)

Through the repercussions of 9/1l, her newly-expanded family and group of friends, her research into history and the Sikh religion, and experiencing the narrow-mindedness of her boyfriend, some of the kids at school, and even her grandparents, Sam realizes the dichotomy of being a coconut. “I thought of Balvir’s definition of a coconut: brown on the outside, white on the inside, mixed-up, confused. And then Uncle Sandeep’s: The coconut is also a symbol of resilience, Samar. Even in conditions where there’s very little nourishment and even less nurturance, it flourishes, growing taller than most of the plants around it.” (247)

“The driver hit the gas and the tires squealed as the truck made a sharp turn and then accelerated right though a bombed-out warehouse onto a parallel alley. Fadi looked from the edge of the truck’s railing in disbelief. His six-year-old sister had been lost because of him.” (25)

Fadi’s father, a native Afghan, received his doctorate in the United States and returned to Afghanistan with his family five years before to help the Taliban rid the country of drugs and help the farmers grow crops. But as the Taliban became more and more restrictive and power-hungry and things changed, Habib, his wife Zafoona, Noor, Fadi, and little Mariam (born in the U.S.) need to flee the country. During their nighttime escape, chased by soldiers, Fadi loses his grip on Mariam as they are pulled into the truck, and she is lost.

Eventually making it to America, the family joins relatives in Fremont, California. “Fremont has the largest population of Afghans in the United States” (56), and Habib takes measures to try to find and rescue Mariam. Starting sixth grade in his new school, Fadi is continuously plagued with guilt over Mariam’s loss and is tormented and beaten up by the two sixth-grade bullies.

However, though Anh, a new friend, he joins the photography club and becomes obsessed with a contest that could win him a ticket to India for a photo shoot but also take him in proximity to Pakistan where he can look for Mariam himself.

Then the events of September 11, 2001, occur and “By the end of the day, Fadi knew that the world as he knew it would never be the same again.” (137). Harassment escalates both at school and in the community. “[Mr. Singh] was attacked because the men thought he was a Muslim since he wore a turban and beard. They blamed him for what happened on September eleventh.” (165)

When the Afghan students have had enough with the school bullies, they band together and confront the two boys, but having them cornered, decide, “We can’t beat them up. That would make us as bad as they are…. Beating them up won’t solve anything.” (232)

Meanwhile, while looking for a photograph that will capture “all the key elements” of a winning photograph and additionally portray his community, Fadi shoots the picture which, in an unusual way, leads to finding Mariam.

In Shooting Kabul, readers meet one family of refugees living in a community of Afghans of different ethnic groups as well as immigrants from other countries. The story also takes readers through some of the background of the Taliban in Afghanistan, relevant at this time.

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to the other novels in this 9/11 book collection.

9-11: The World’s Finest Comic Book Writers and Artists Tell Stories to Remember. DC Comics, 2002.

The creative talent of DC Comics donated their time and work for this volume which tells the stories and shares the images of September 11, 2001, through 39 graphic stories that reveal diverse perspectives. This volume is dedicated to the victims of the September 11th attacks, their families, and the heroes who supported and supplied aid. All profits are to be contributed to 9-11 charitable funds. The book is a celebration of heroes and a memorial to victims.

Story contributors include writers and artists who will be well-known to comic fans and graphic readers, such as Will Eisner, one of the pioneers of American comic books and graphic novels; Stan Lee, primary creative leader of Marvel Comics; and Neil Gaiman, New York Times bestselling author of more than twenty books.

Divided into five sections: “Nightmares,” “Heroes,” “Recollections,” “Unity,” and “Dreams,” the diversity of stories and artwork will appeal to a variety of YA readers. There are integration of the DC heroes throughout. Readers can select the stories and artwork that speak to them. As with most anthologies, the quality and appeal of the stories and the work vary. Many are well executed and moving, others are weaker; some portray complicated emotions, and others lack depth; some may be triggering, others may not connect the reader to the events. Some are may come across as more political than others.

One of the first graphics, “Wake Up,” relates the story of a young boy who dreams of his mother, a NYC police officer who lost her life. He wakes up, “doing what Mom said, standing tall because I want the bad guys to know…I’m not broken. My heart is unbreakable.” (23)

In the Unity section, in the story “For Art’s Sake” a comic book artist struggles with the value of his profession after witnessing the fall of the Trade Center. He tells his father, also an illustrator, “Don’t you feel a little guilty? Because we’re sitting here telling meaningless stories about imaginary heroes while out there, hundreds of real heroes are dead.…All comic books, all art for that matter! Painting, movies, tv…it all seems so frivolous, you know?”” (121-2) His father counsels him, “Listen, I’m not saying artists are near as brave as the men or women who ran into those buildings. We’re not. But we do have a role to play. We answered a calling just like they did.…We help our country cope with tragedies like this one. We make people think, we help them laugh again, or maybe we just give ‘em a place to escape for a little while.” (124)

I would recommend this book to readers who are engaged by graphics, are open to a range of interpretations of events, and already have some knowledge of the events of 9/11.

* * *’

…and 6 Picture Books

Curtis, A.B. The Little Chapel That Stood. Oldcastle Publishing, 2005.

Davis, Amanada. 30,000 Stitches: The Inspiring Story of the National 9/11 Flag. Worthy Kids, 2021.

Deedy, Carmen Agra. 14 Cows for America. Peachtree Publishing Company, 2009.

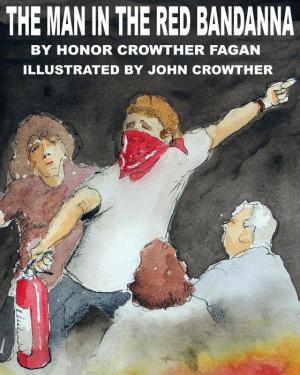

Fagan, Honor Crowther. The Man in the Red Bandana. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Gerstein, Mordicai. The Man Who Walked Between the Towers. Scholastic, Inc., 2001.

Kalman, Maira. Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of John J. Harvey. G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers, 2002.

Lesley is the author of

- Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core

- Comma Quest: The Rules They Followed. The Sentences They Saved

- No More “Us” & “Them: Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect

- The Write to Read: Response Journals That Increase Comprehension

- Talking Texts: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum

- and has contributed chapters to

- Young Adult Literature in a Digital World: Textual Engagement though Visual Literacy

- Queer Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the English Language Arts Curriculum

- Story Frames for Teaching Literacy: Enhancing Student Learning through the Power of Storytelling

- Fostering Mental Health Literacy through Adolescent Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed