Thanks Celeste.

A Look at the 2020 America Indian Youth Literature Award

Prior to 2020, this biennial award has been celebrated at a separate awards ceremony. When I had the opportunity to attend the awards ceremony at ALA Midwinter (Seattle, 2019), it was held off site, at the main branch of the Seattle Public Library. While this celebration had a feeling of intimacy and connection because all in attendance were there specifically to uplift Indigenous youth literature, I looked forward to this award becoming a part of the very widely celebrated ALA Youth Media Awards.

Being announced together with the ALA Youth Media Awards is so important because these particular awards are often a major influencing factor in how books become a part of curriculum and vetted for classroom use. Additionally, award winners see an increase in sales, and I imagine publishing houses across the country are crossing their fingers that their publications are chosen for one or more awards. As much as I know that there are always plenty of wonderful books that do not win awards because of timing, because of the make up of awards committees, or other reasons, I also know that winning one of these awards is a huge measure of success.

The middle school award went to Indian No More, written by Charlene Willing McManis. Umpqua/Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde) with Traci Sorell (Cherokee), published by Tu Books in 2019.

The young adult award went to Hearts Unbroken Written by Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee) published by Candlewick Press in 2018.

| There were also eleven honor books including I Can Make This Promise by Christine Day (Upper Skagit/Nooksack/Blackfeet/Nez Perce) published by Harper Collins in 2018. I Can Make This Promise is the story of Edie, a seventh grade girl living in Seattle who is curious about her Indigenous heritage and the Indigenous side of her family. Her mother is of Suquamish heritage and had been forcibly removed from her family and adopted by a white family. She had grown up not connected to her heritage, but only learned of her family story as an adult. She named Edie after he mother, whom she never knew. Edie’s journey to learn about this side of her family helps the reader understand a little bit about Indigenous history and identity and the Author’s Note gives additional context for this learning, including a mention of support for the Indian Child Welfare |

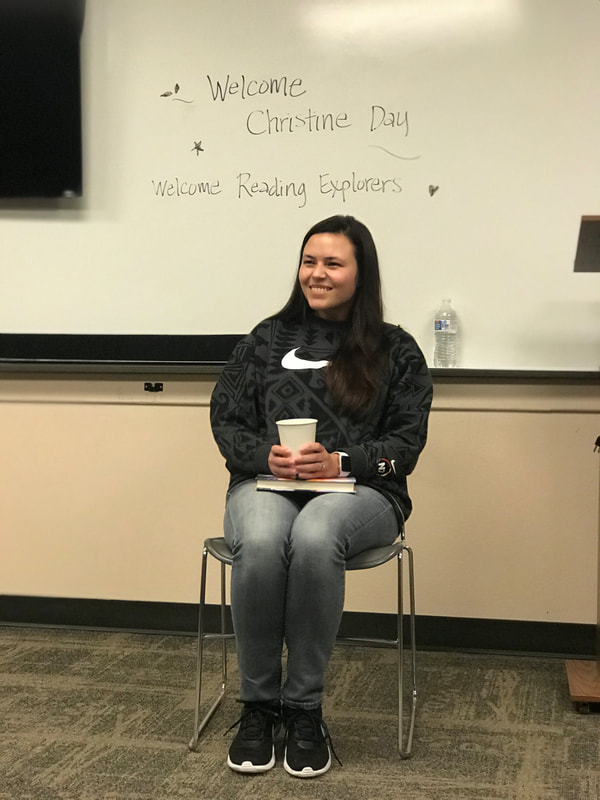

| A few days ago, I had the great pleasure of attending the Reading Explorers book club with Christine Day at the Lacey Timberland Regional Library. The room was full of kids holding their copies of Christine’s debut novel. I met Christine in November when she was at NCTE/ALAN in Baltimore. In her talk at ALAN, she highlighted how the power of stories draws us together at ALAN and informs our teaching. She also discussed the dearth of Indigenous authored literature for children, advocating for teachers to read Indigenous stories and provide these books to their students. She was speaking to the large and wonderful room full of passionate readers and educators. But in our little library room, she was speaking to kids mainly between the ages of 9-12, and some curious adults, including a student in my children’s literature course. Many of the students had seen her earlier that day, or the day before, during her local school visits, and wanted another chance to engage with her. First, she read a brief passage from the book. This passage, she said, was the only part of the book that didn’t change through all the various edits. Most of the time, however, was given over to questions from the Reading Explorers, themselves. Some of the questions were like this: |

But most of the questions fell into two main categories.

1.Inspiration: What inspired you to write this? Why did you give the characters the names you did? How did you come up with your ideas?

2.The Future: Will you write another book with Edie, the main character? Are you writing another book now? When will your new book come out? What happens after the end of the book?

The children asked some very repetitive questions about this sequel that is not actually planned yet. In fact, they were not asking but demanding that Christine continue Edie’s story, not taking Christine’s hopeful ‘maybe’ as an answer. I thought of a moment from Chimamanda Adichie’s much celebrated TEd talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” in which a reader stops her to tell her she must write a sequel and tells her exactly what should occur in the plot. Adichie says she is charmed by this reader feeling strong ownership of her story in a country where it was wrongly assumed that the people didn’t care to read very much.

I teach preservice teachers, and at the beginning of each semester, I ask students if they enjoy reading. The overwhelming answer is always, “No, but I did when I was a kid.” Watching the Reading Explorers engage with Christine with overflowing interest and enthusiasm, I tried to imagine the preservice teachers I work with as these children: eager, curious, and filled with the power of stories. I try to imagine schooling and curricula that doesn’t damage this love of reading, but nourishes it. I hope I am helping students in my classes to grow into teachers who re-learn to love reading, passing that love onto their future students.

And by writing and publishing Indigenous literature for youth, authors and illustrators are inspiring and modeling for Indigenous youth that their stories are valid, necessary, and worthy of writing and sharing broadly.

As I was leaving the event at the library, the line was still long for Christine to sign the kids’ books. I walked out behind a child and parent and overheard their conversation.

“Dad, do you think I can be a writer someday?”

“Of course you can, honey.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed