One of the great things about attending a conference is meeting people who share your interests, especially when they are in a different field. In June 2014, at the first annual LSU YAL Conference and Symposium, I had the pleasure of meeting Martha Guarisco, a sixth-grade English teacher at Episcopal School of Baton Rouge. At my breakout presentation on Harry Potter and depictions of mental illness, we discovered we were both interested in the ability of YAL to promote empathy towards others. That connection launched a successful collaborative study.

Ms. Guarisco had already planned an academic unit for her students using R.J. Palacio’s best-selling book Wonder. It is the story of a 10-year-old boy with severe facial deformities attending school for the first time, and struggling to be accepted by his peers. In an effort to use the book to build not only reading skills but also character, Ms. Guarisco had developed a series of empathy-building activities to go with the reading. She asked me if I knew of a way to measure empathy before and after the academic unit.

· Perspective Taking: the tendency to spontaneously adopt another’s point-of-view

· Empathetic Concern: the tendency to feel pity or concern for another person in distress

· Personal Distress: the tendency to feel emotional pain yourself when seeing another person in difficulty

Both my work and others’ (e.g. Mar and Oatley, 2009) suggest readers of all ages can use fiction as a “safe zone” in which to rehearse emotional reactions towards others, even in circumstances when it might be difficult to feel empathy in real life. For example, real-world Personal Distress scores tend to correlate negatively with Perspective-Taking, because it is hard to objectively adopt another’s point of view when you are yourself distressed. In the fictional world, it seems to be easier for a person to feel both types of empathy simultaneously; therefore Empathic Concern and Perspective-Taking scores for fictional characters correlate positively (Nomura and Akai, 2012).

Ms. Guarisco and I arranged to administer the IRI to her students anonymously by computer. We tested the students in early September 2014, just before they began the Wonder unit. In mid-November, after the unit, we tested them again, and compared the two sets of scores. The Wonder-based empathy exercises seemed to be effective; statistical analysis showed a significant increase in Perspective-Taking scores (Fig. 1) Interestingly, the Empathic Concern, Personal Distress and Fantasy Scale scores did not increase. This reassures us that the increase in Perspective-Taking is probably a direct result of the Wonder unit, rather than the children trying to meet teacher expectations by giving “nicer” answers on the second round of testing. If that were the case, we would have expected to see increases in all four subscales.

Our study proved timely. In July 2014, s Ms. Guarisco and I were preparing our experiment, a study from Italy (Vezzali et al., 2014) was published, and quickly made headlines. Using a similar before-and-after experimental design, Vezzali’s team tested elementary-aged children and found that a six-week unit of reading and discussing specific Harry Potter scenes that related to prejudice reduced negative feelings toward a minority group--in this case, immigrants. Furthermore, the reduction was greater in the students who identified more with Harry, and less with Voldemort.

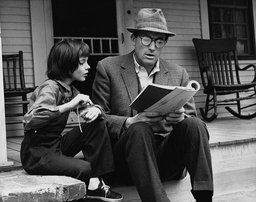

The great Atticus Finch once told Scout that understanding a person required that “you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” The ability to take another’s perspective is an important cognitive aspect of empathy and likely the first step towards reducing stigmatization of someone different. Our study suggests that you don’t need an ultra-popular cultural phenomenon like Harry Potter to cultivate empathy in children through reading. All it seems to require is the right book, the right lessons and the right teacher.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed