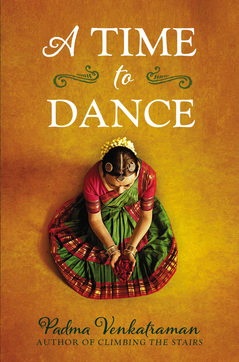

I recently finished Padma’s newest novel, A Time to Dance, and I had the opportunity to interview her this week. It was great fun. I encourage you to check out her website and her blog. Explore the multiple starred reviews that have appeared at Kirkus, Booklist, and Voya, among other sources. Unfortunately, we don’t have the space to capture all of the conversation, but I hope this wets your appetite for the works of this remarkable author.

Steve: Both Climbing the Stairs and A Time to Dance are set in India. How closely do these stories reflect your own youth or other members of your family?

Padma: A Time to Dance is influenced both by a Bharatanatyam dancer whom I saw as a child who later overcame physical disability to continue dancing and by an aunt who lost the use of one of her legs as a result of a childhood polio attack. My aunt did not have an amazing modern prostheses (and even today, like Veda in A Time to Dance, few Indians can afford to have such marvelously engineered prosthetic limbs), but she was the most active of all my aunts, joining in our outdoor games and participating as best she could. We never thought of her as disabled, just differently abled.

Steve: I love the strong female characters in both novels. Can you talk about some of the influences for these characters?

Padma: The lack of strong female role models in my own life and in books when I was growing up, oddly enough, makes me invite strong female characters into my imagination, I think. (Padma also mentioned in our discussion that her own reading history is connected to a grandfather’s library and her range of exposure to western literature and literature from her native India is quite similar to the books that Vidya reads in Climbing the Stairs.)

Steve: What would you hope non-Indian readers would glean from your novels?

Padma: I do want to make the point, here, that I'm American. Unfortunately, we also have stereotypical images of who's American. I have dark skin, I'm as comfortable wearing Indian clothes as I am wearing Western outfits, and, having lived in 5 nations before choosing to become American, my accent is a hodgepodge. My husband is from the West and my child is bi-racial. So it's natural that both East and West find expression in my work. But I am American, as much, if not more than someone who was born a citizen - because I decided this is what I wanted to be.

Steve: Both novels that we are highlighting here are distinct in style. The first is a prose narrative and the second is a written in free verse. What did you find were the artistic challenges and moments of successes of both?

Padma: On the one hand, I feel like I'm merely transcribing voices I hear in my head (when I hear voices in my head, luckily, rather than trying to converse with them, I try to listen and write down what they're saying). So I could say that each protagonist spoke to me in a different way - and that would be true.

On the other hand, writing is not just inspiration, but also a lot of hard work.

A writer must cultivate a schizophrenia that separates the listening to the voice and letting the writing flow part of the self from the axe wielding editorial self. And I think this editorial, more objective, part of myself told me that verse was a natural choice for a book that dealt with dance and the power of art - abstract aspects of the story that can, in a way, be captured through rhythm, which is so central to verse. Most important, perhaps, verse is also, pretty much, the only way (for me, at least), to convey the deepening of Veda's spiritual understanding and her spiritual growth - a theme that's central to her story and that makes her story unique.

My challenge, in using this form to write A Time to Dance, was to overcome my feeling of inadequacy. I have always loved to read poetry and I read a lot of poetry even today. But I've never analyzed it in the way someone might in a literature course. At one point, I was so afraid that I wrote an entire draft in prose, but then I lost Veda's voice, I couldn't see her any more in the movie that plays in my mind when I write.

So, I knew I had to do something to give myself permission to write a novel in verse. I sat in on a graduate class in poetry, took a short poetry workshop with Richard Blanco, discussed poetry with colleagues who are professors and poets and read many YA novels written in verse or in vignettes, such as Kimberley Newton Fusco's Tending to Grace, An Na's A Step from Heaven, Patricia McCormick's Sold, Carolyn Coman's What Jamie Saw, Sandra Cisnero's The House on Mango Street, Tracy Vaughn Zimmer's Reaching for the Sun, Thanhha Lai's Inside Out and Back Again, Gary Paulsen's Dogsong, Jacqueline Woodson's Locomotion, and Karen Hesse's Out of the Dust. My editor, Nancy Paulsen, is also someone who is a fan of this form, and she encouraged me strongly and stood by me through the years of struggle as this novel took shape.

As for moments of success, I feel tremendously grateful and relieved that the novel received starred reviews in 5 journals - Kirkus, Booklist, VOYA, SLJ and BCCB - and that so many reviewers, in newspapers all over the country and online have loved A Time to Dance. I am also thankful for each time someone lets me know that the novel touched them. One of the most glorious moments thus far, was when someone described A Time to Dance as a Siddhartha with a female protagonist. But, beyond this external recognition, my deepest reward comes from knowing, deep inside, that I did my best to tell the story of the character who honored me by visiting the landscape of my mind.

Steve: I love your strong use of central metaphors in both books. Do you see metaphors and symbols as a guiding force in your creative process?

Padma: Although my first 2 novels are prose narratives, their styles differ: Climbing the Stairs is past tense and Island’s End is present tense. A Time to Dance, of course, is as you point out, quite a departure - the first two tend toward lush, evocative verse; A Time to Dance is written in lean, spare prose. As stories, the three are very different as well, but there's one thread that runs through them. In some way, each of them explores the protagonist's search for spiritual meaning.

In Climbing the Stairs, Vidya discovers the divide between the all-accepting and all-embracing, the philosophical underpinnings of her faith, and the extremely divisive social customs that some members of her family ascribe to her faith. In Island’s End, Uido trains to become the spiritual leader of her tribe. And of course, in A Time to Dance, more than with the other two novels, the protagonist's growth is inextricably entwined with her spiritual musings, the awakening of her compassion, the discovery of the deeper aspect, and the power of her art.

Spirituality is a damnably hard topic to address - in a novel for any age group - but especially, I think, in a novel for young people (because one absolutely must stay away from pushing any particular religion; as an author for young people, you cannot, must not, be didactic). But I think it's what sets Veda's story apart, what makes her story so much more intriguing, what makes her special as a person. And I feel like I have grown, tremendously, as a writer, by taking on this tremendous challenge of writing a story with this very rarely-explored theme of spiritual growth.

But to get back to your question - I also feel like metaphors and symbols are inextricably entwined with spirituality of any sort, and so it is inevitable that they play an integral role in any novel that takes on the very difficult task of exploring a character's spiritual journey.

Steve: Thank you

I hope you explore Padma’s novels and some of the books she mentions during her interview. If you happen to be attending the National Council of the Social Studies (NCSS) annual convention this year, you can hear more from Padma. She will be on a panel—Studying the World through Story: Using Fiction to Implement CCSS. I think she has much to offer the readers who find her novels. I know I thoroughly enjoyed them; furthermore, I learned something about the world and myself.

Until next week,

Steven T. Bickmore

RSS Feed

RSS Feed