| Dr. Chea Parton is a farm girl and former rural student and high school English teacher. She’s currently an assistant professor of instruction at The University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation “Country-fied city or city-fied country?”: The impact of place on rural out-migrated literacy teachers’ identities and practices (2020) won honorable mention for the American Educational Research Association’s rural education special interest group’s dissertation award. Her research focuses on the lived experiences and identities of rural and out-migrant students and teachers as well as how they’re (in)visible in classrooms and YA literature. |

I also thought about the years we did “recycled Christmas” with my dad when there wasn’t enough money for new presents. Essentially, he would gift us things of his that he knew we loved. It wasn’t until I was telling my friends at school about it that I realized it wasn’t something that everyone did and that it meant something about my social class. I recognize now that this was class injury, something I experienced affectively and emotionally as I was reminded of our working-class status.

Now, I live stuck somewhere between these two identities. For example, I have cultivated the habit of never going to the doctor unless something is seriously wrong because of its expense and haven’t been to a primary care physician in a decade. I can’t stand food waste, so I strategically prepare less food than I actually want to eat because I know that I’ll end up eating whatever my kids leave on their plates. But I also had no problem buying all those presents.

These experiences with class injury, class mobility, and identity feel more visible now because of my recent work with place and class in YA literature. As part of Drs. Sophia Sarigianides and Amanda Thein’s special issue of English Journal, I began thinking through class representation in YA as well as how to teach it in classrooms. An extension of that work (thanks to Dr. Sarigianides’s generous invitation!) resulted in an exploratory comparative content analysis of the representation of social class across rural and urban places in YA literature.

One of the things that Dr. Sarigianides’s ongoing current research demonstrates is that we often have trouble figuring out where and who we are in terms of social class (to learn more, see our pre-recorded NCTE presentation), which I don’t think is an accident. So, learning how to have conversations about social class and how we experience it in our lives is powerful and important. One way we can do that is through our reading and discussion of literature. For this post I wanted to briefly outline what I found through my analysis and make some suggestions for how to address social class, especially as connected to place, in an ELA classroom.

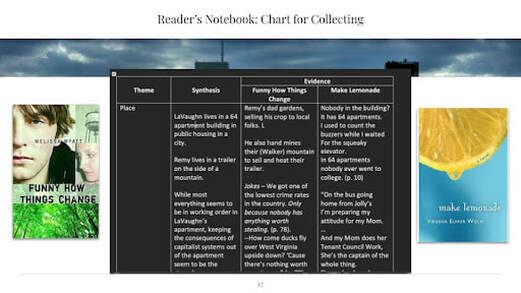

There were more similarities than I expected to find. For example:

- Remy, Jolly, LaVaughn all have jobs as teenagers that are more than a slush fund.

- Remy and LaVaughn have special (though different) connections to their places.

- All speak a nonstandard variety of English

- There is an understanding that it's up to them (rather than the system) to make lemonade

But there were also some important differences connected to place:

- Remy doesn’t feel like he needs college to get out of Dwyer but LaVaughn sees college as her ticket to a good, middle-class life.

- LaVaughn lives in a high-rise building in public housing and Remy lives in a trailer.

- Remy is used to the switchbacks and turns of the mountains and knows how to read the weather by feel.

- LaVaughn knows bus routes and stops and not to go into the laundry alone

If they traded places, neither one of them would know how to navigate and be in the other’s place—even though they occupy similar class positions. And despite their shared class positions, the differences in their places lead them to be stereotyped in different ways. There are important differences between the assumptions that people make about “trailer trash” and folks from “the projects.” The intersectional identities assumed to belong to each and the way they are connected to power and privilege offer important opportunities for critical examinations of systems of power and the ways they interact to position people within society.

- Introduce the concept of social class through the crayon activity. (You can learn more about that here as well as listen to Antonia talk about it in our pre-recorded NCTE video.)

- Discuss how place shapes those classed experiences. Using Jason Reynolds’s Time 100 talk would be an excellent resource here.

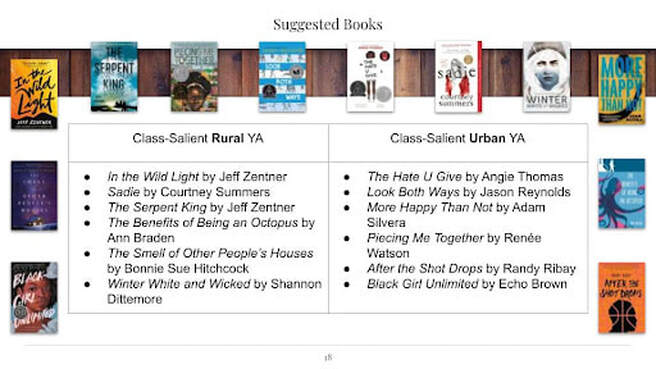

- Run book clubs where some students read class-salient rural books and others read class-salient urban books.

- Ask students to keep readers notebooks where they take note of any mention, description, or illustration of class and/or place, jotting their thoughts and reflections in their notebooks.

- Have students talk across their books, essentially performing a comparative analysis similar to the one I describe (albeit briefly) here.

- Ask students to complete a project that allows them to use what they’ve learned to continue to explore social class in their lives and be activists in their community and the world. Possibilities include:

- Writing their own autobiographical/fictional, multivocal, poetic examinations of their class position(s), movement(s), and/or injury(ies).

- Examining community supports for folks experiencing lower SES social class positions and proposing ways to do it better.

- Writing their own autobiographical/fictional, multivocal, poetic examinations of their class position(s), movement(s), and/or injury(ies).

Helping students better understand and talk about social class can be facilitated through YA literature in ways that can lead to the kind of social action and activism that we need to make our world a more equitable place.

If you’d like more detail on any of the ideas found here, please check out our pre-recorded NCTE session, read the social class issue of English Journal, and don’t hesitate to reach out to me with questions at [email protected].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed