| After my (Steve’s) freshman year in high school, my best friend asked me if I wanted to go work on his uncle’s farm. I said yes. Thus began three summers of intense farm work that framed much of how I viewed the world and interacted with other people. I learned how to work hard. I learned the difference between a pair of pliers and a wrench; and more importantly, the difference between a wrench and an “effen” wrench. I also learned that I was going to college. After the first summer, I knew that college provided a variety of different work options that went beyond dark, early mornings, cold water, mud, and heavy lifting. In addition, much of what I learned, I learn alongside undocumented Mexican laborers who worked hard and kindly taught us the tricks of how to move pipe through sugar beets, potatoes, and grain. In the rural farm land outside of Nampa, Idaho quite different from Las Vegas, there were 400 people moving pipe. About ten of us were high school students. Most of the rest, were Mexicans who traveled back and forth between Mexico and Idaho for six to eight months at a time. There were not taking the work from adolescent, most of those adolescent, at the time, wouldn’t take the work. Most of the other adolescents we meet at church, at drive-ins, or other activities thought that we were crazy for doing the type of work we did. I also learned not to judge others just because they were different or their language was different. They were kind, funny, and tried to be inclusive. For two of those years, my buddy, David, and I lived in the same labor camps that were provided for the other workers. The sound of Spanish became familiar and even though I didn’t learn to speak it during those summers. When I began to study Spanish intensely, it was familiar and came easily. |

Below Briana Asmus introduces us to several YA novels that might offer the opportunity for a vicarious experience with immigrant realities.

What’s in a Border? Using YA Lit to Challenge Dominant Narratives in U.S-Mexico Border Crossing by Briana Asmus

| A few years ago, I took a position as a literacy consultant at a summer in a migrant education program near the lakeshore in West Michigan. Many of the kids we served had immigrated from Mexico, crossing the border in south Texas and becoming a part of the migrant farmworker stream. There were many families from Mexico, but there were also families from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Many had “crossed” undocumented, and a few had crossed alone-- a truth rarely spoken because of the stigma it carried, the danger it could put students in, and the trauma that frequently accompanies the journey. |

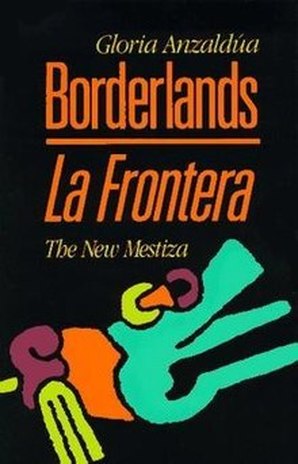

| Dominant narratives in Trump’s build-the-wall presidency would have us believe that “illegals” who cross the border are criminals, looking to exploit our resources, take our jobs, and take advantage of our social systems (among other things). In my experience, and as told by the stories in Illegal, The Border, and Enrique’s Journey, these deficit narratives are gross oversimplifications of deep-seated political and historical dynamics that persist outside of the characters, yet control their every move. In Borderlands/La Frontera (1987), Gloria Anzaldua writes “The U.S-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds” (3). This “grating” may be the only common experience between people in stories of border crossing. In a place where everyone is forbidden, unwanted, and simply trying to live, there is not one single narrative, but rather a symphony of the voices of thousands who have run out of options. Bringing these voices into the classroom not only fosters empathy, but provides a necessary counter-narrative to what we hear on the news and in the media. |

| Bettina Respito’s Illegal adds the voice of a 15-year-old girl, Nora, to the symphony. Nora crosses the border (along with her mother), in search of her father, who leaves the family in search of an income in the States. Crossing the border as a (young) woman poses its own unique set of challenges. Gendered experiences of border crossing would be one theme to explore with students, in addition to themes of loss, resilience, family and faith. The imagery in Illegal is filled with recurring sensory details that form memory in the protagonist and the reader. Another way this text challenges dominant narratives is by providing a story that starts in a small-town in Mexico, largely untouched by narcos. In addition, much of the story takes place in Houston, demonstrating that problems don’t disappear once the border is crossed, in fact, it’s often quite the opposite. |

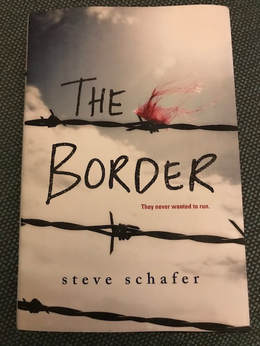

| The Border by Steve Schafer offers another perspective, this time from a teen and his three friends who attempt to cross together. It’s fast-paced, and will appeal to students who may struggle with getting “hooked” on a text-- escape from narcos is at the core of the story. The characters challenge stereotypes in different ways, via gender roles and representations of poverty. For the majority of the text, the group of friends encounter very real hardship in the form of gangs, bullets, snakes, and dehydration as they attempt to cross the desert into Arizona. One salient moment is when the protagonist realizes the border is merely some barbed wire between posts; more of a statement (you don’t belong here) than a physical structure. This would be an excellent opportunity for students to the messages behind current rhetoric. |

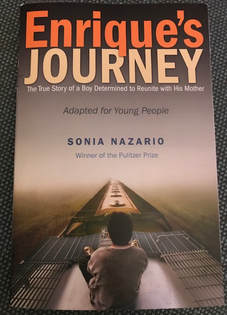

| Although not necessarily a YA text, I have to mention Enrique’s Journey: The Story of a Boy Determined to Reunite with His Mother. There is an adapted version of this text for young readers. Enrique’s Journey is the true story of an adolescent Honduran boy more than a decade in the making, who tried to cross the border six times before he is successful on the seventh in order to reunite with his mother. This text (or parts of it) can add an important missing piece to the narrative of border crossing; those living in Central America who need to ride “The Beast”, a relentless train through Mexico that takes the lives and limbs of the hundreds who ride atop its cars each year. These travelers face additional hardships, many of them a result of increased discrimination. |

Note: Since submitting this post to Dr. Bickmore, President Trump has announced his motion to send thousands of troops to “secure” the U.S./Mexico Border. It’s important to note that according to the Department of Homeland Security, border crossing arrests are at a 46-year low, while arrests on the interior for non-violent immigrants (whose only offence was being undocumented) have increased over forty percent (see this article for references). ICE has conducted several sweeps in Grand Rapids, Michigan where I teach. K-12 teachers tell me stories of kids “disappearing,” and some schools are creating safety plans in case of an ICE visit. I have started inviting immigration lawyers to be guest speakers in my seminars. The border is now everywhere.

Briana Asmus is Assistant Professor and Director for ESL and Bilingual Programs at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, MI. She can be contacted at [email protected].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed