| Susan Cridland-Hughes, Ph.D., is the Associate Professor of English Education in the College of Education at Clemson University. Her research focuses on the intersections of social justice, critical literacy, and orality in out of school educational spaces, particularly debate and debate education. Her work has been featured in the Journal of Language and Literacy Education, Journal of Adolescent Literacy, and English Teaching: Practice and Critique. Jung Kim is Professor of Literacy in the Department of Education at Lewis University and, when not working, can be found either running or reading. A former English teacher and literacy coach, she is interested in critical literacy, issues of equity, and coffee. She writes about teaching with graphic novels, children's and young adult literature, and Asian American education. Her most recent book is on the racialization of Asian American teachers. |

South Carolina’s Expanding Landscape of Book Challenges:

We start this post with a snapshot of what is happening in South Carolina. Susan’s children attend schools in the Greenville County School District, the largest school district in the state and 44th largest in the country. Greenville County Schools has a book challenge policy whereby parents can challenge books used in the classroom by filing a form, the “Request for reconsideration of instructional materials.” The policy provides for the composition of a book challenge committee for each of the instructional levels: elementary, middle, and secondary. The policy also provides for the composition of the book challenge committee; notably, all book challenge committees provide for the inclusion of a member of clergy, and, for secondary schools, there is a provision for the inclusion of two student voting members. The policy indicates that the committee will review and issue a decision, but that the decision can be appealed to the Superintendent and the appeal will be reviewed by the full school board.

I am hesitant to remove texts from shelves, recognizing that school libraries- like traditional public libraries- provide opportunity for self- selected reading… I also recognize that it would be incredibly difficult to have a book in an elementary school library that is limited to 5th graders and for the District to guarantee that younger students would not have access to the book.

In this case, the board chose to restrict instead of remove; the result, however, is that a child will be unable to seek out this text independently until the age of 14, far beyond the age recommended by the book committee.

While there is a challenge process that was ostensibly followed in both contexts, there have also been stories about books being removed from libraries without a formal and official challenge from parents. GCS writes in its policy that books will not be removed until the challenge has been adjudicated. However, the book Genderqueer by Maia Kobabe was removed based on a letter from South Carolina governor Henry McMaster where he referred to the book as “meeting the statutory definition of obscenity” (McMaster 2021) and referred the matter to the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division. School libraries do not appear to have the protection that classroom instructional materials are afforded; either that, or the Governor can unilaterally remove any text that he sees as problematic. Most concerningly, it appears South Carolina has a policy that includes a carve-out for anything considered prurient or pornographic, and books with LGBTQIA+ representation are at greatest risk of removal.

Jung is in Illinois and the president of her local elementary school district, which hosts almost 6000 students amongst eight pK-5 buildings and two middle schools. The Illinois Association of School Boards has a set policy on “Teaching about Controversial Issues” which requires that the Superintendent ensure all school-sponsored presentations and discussions be age-appropriate, consistent with the curriculum and be education, informative and balanced, respectful of the rights of others, and is not tolerant of profanity or slander. The community within which she lives borders Chicago and is considered a very progressive community and highly engaged in discussions of race and equity. During her tenure on the school board (3 years), there have not been any book challenges that have come before the board. In fact, the district adopted an anti-racist curriculum policy two years ago that included the young adult version of Stamped by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds and Tiffany Jewell’s This Book Is Antiracist (both books that have been challenged elsewhere). While the board has received a few letters critiquing the antiracist curriculum, most community members and parents have been in support of the curriculum.

Because of the nature of mass media today, though, the board has also received complaints from individuals outside of the district about various policies and procedures that are seen as pushing a liberal agenda–whether it’s about books or about masking. Last year, one local family took to national conservative media to argue against the antiracist curriculum– that talking about race and inequity perpetuates racism and inequity. A different online conservative media source also criticized the “critical race theory curriculum” being pushed in the district and made sure to publish Jung’s photo (she is Asian American) and the board vice president’s photo (she is African American) alongside the article. Neither of them was referenced or cited in the article but their pictures were used. One cannot help but wonder if they weren’t women of color if the news source would have printed their pictures. In this vein, local issues have become national ones.

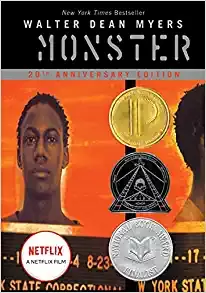

While the district does offer a process for challenging a book for being “offensive or controversial,” such challenges generally do not come to the board and the board does not vote on novels used in classrooms. This is what happened when seven parents challenged the use of Walter Dean Myers’ Monster in the middle school. A committee reviewed the book and decided it was appropriate for seventh grade. The decision was presented to the board but not as one on which their vote was expected. This is, in fact, what the Illinois Association of School Boards advocates–the “balcony view.” School board members should make high level decisions, as if from a balcony, and not get in the weeds with the daily goings ons in the district. While Jung is a former teacher and current teacher educator, most school board members are not highly trained experts in schools and education. Regardless of expertise, the board’s place should not be dictating curriculum and making decisions about what should or should not get taught in schools. It has been frustrating and appalling to see school board members across the country work to silence the voices and stories of those that have most often been pushed to the margins. Schools should encourage a diversity of voices that humanizes all.

Some resources for advocating for authors and readers

While this post is predominantly about the situation in South Carolina, South Carolina is by no means the only state where the freedom to read is under attack. NCTE just published a statement denouncing the challenge in Virginia (again to Genderqueer), that could endanger sales of the book throughout the state.

We wanted to leave you with some resources for advocating for freedom to read when it comes to literature in schools.

- NCTE Intellectual Freedom Center: https://ncte.org/resources/ncte-intellectual-freedom-center/news-and-updates/

- ALA Challenge Support Center: Note, this is primarily for public libraries, but it has some best practices for responding to challenges.

- American Associate for School Librarians:

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund:

If nothing else, you can track the challenges filed in your local district and reach out to your elected school board official to formally request that they support the freedom to read. Authors, teachers, and students need informed members of the community to push back against censorship.

References:

McMaster, H. (November 10, 2021). Letter to State Superintendent Molly Spearman.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed