| Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides is Professor of English Education at Westfield State University. Her research interests include antiracist teaching in the ELA classroom through literature, the study of social class through literature, and representations of adolescence in YAL. Her recent book, co-authored with Carlin Borsheim-Black, earned AACTE’s 2022 Outstanding Book Award in Education. Carlin Borsheim-Black, Professor of English Education at Central Michigan University, researches possibilities and challenges of antiracist teaching, especially in predominantly white spaces. Her recent book, Letting Go of Literary Whiteness: Antiracist Literature Instruction for White Students, co-authored with Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides, was nominated for the Grawemeyer Award for Education. |

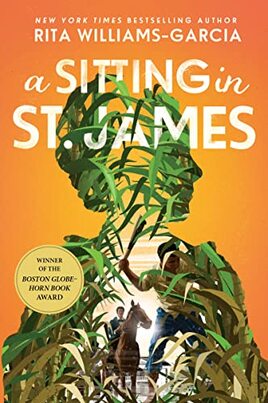

Set in St. James Parish, Louisiana in the 1860’s, A Sitting in St. James is the story of the Guilbert family. The matriarch, Madame Sylvie Guilbert, finds herself in Louisiana after Bayard Guilbert travels to France to coerce her into marriage. Madame journeys, first to Haiti and then to America with little more than a family heirloom, a signet ring that connects her to her family’s vineyard and the social education she received as a member of the queen’s court.

After Bayard dies, Madame is left to run the struggling plantation with her son, Lucien, and his son, Byron, who is expected to marry well and produce an heir to keep the plantation viable and to carry on the family legacy. From her salon, Madame Guilbert tries desperately to hold her family to rigid social norms of polite French society--the old world--as their last best hope for marrying Byron off to a family of higher status and social standing. In 19th century Louisiana, with its complex mix of racial and socioeconomic standing among whites, slaves, free Blacks, and mixed-race people—retaining this status serves as one of the central conflicts of the novel.

A key strategy for sealing in her own and her family’s social standing is Madame’s insistence on sitting for a portrait, one the family cannot afford, that is to be completed by a French painter descended from a painter who portrayed Queen Marie Antoinette herself. We see this portraiture effort—the sitting—as a central symbol helpful for unpacking the ways in which whiteness attempts to work to seal in its power.

Symbolism

Whiteness as property. Readers are educated as to the purpose of sittings for portraits alongside Jane, Madame’s protege, the daughter of a wealthy neighbor who cannot seem to take on apt gender norms for a young lady. As Madame displays the jewelry she will wear, the way she will dress her hair for the sitting, she explains to Jane, “You see, a portrait is for eternity” (306). Comparing the sitting to an important party, Madame continues, “[W]hat happens at the party can last a lifetime, for the lifetime of the children and grandchildren to come” (307). As such, a portrait—like the complex social negotiations of 19th century formal parties—affects the social standing for current and future generations, something Madame seeks to stabilize for herself and her progeny given the family’s financial troubles.

So what is the social standing that Madame seeks to reinforce, to establish, to ensure? Her connection to the French royal court of Queen Antoinette and the social power that came with that. Her wealth, signified by the ring smuggled out with her from France. But also, in the slave-owning, plantation setting of 1860s Louisiana—and in a home where her profligate son, Lucien, seeks to introduce his mixed-race daughter, Rosalie, as a member of the family—she also seeks to seal in her whiteness and its place in the racial social hierarchy. The sitting, then, functions as a key symbol of whiteness: an opportunity to seal in racial identity and social class status onto canvas for eternity. It is one of the more valuable things she has to pass down to future generations.

Whiteness is an illusion, an invention. Racial and social status are both constructs, Madame’s social standing an illusion. The irony of the portrait is that Madame cannot afford the luxury at all. The portrait artist, Le Brun, begrudgingly agrees to do the painting as a favor to Countess Duhon, the favorite aunt of Madame’s future daughter-in-law. And Madame and Lucien know they will have to leverage what they have left to finance the purchase of the portrait.

“No one in polite society follows these practices. And when they do it, it is all for show” (425). Though Le Brun makes this statement about a different social practice, it easily works to sum up his view of her worldview as well, and even of portraiture. Le Brun is part of a group of artists who work to experiment aesthetically through portraiture, including by focusing on subjects like the Black field hands cutting cane outside, something that outrages Madame. He is aware of how Madame sees the enslaved people on her plantation and how she seeks to use the portrait strategically in society. Given his concerns about the family’s ability to pay him for his work, readers might expect some tension around the entire sitting, tension that proves satisfying in its ultimate handling.

Sitting for a portrait is an outdated practice, one that “polite”—wealthy, white, European—society used to engage in but does no longer. It was intended to offer viewers a curated view of someone powerful, often with invented details to secure the subject’s social—and often political—status.

Yes, portraits work to affect the workings of those social constructs, but ultimately, they also present artists—and viewers—and in this case, Madame’s intended audience, for an opportunity for subversion and disruption of those very social norms. And, in the hands of Williams-Garcia, this subversion works to satisfy readers’ disgust with the social norms Madame seeks to uphold.

Whiteness is a detriment to us all. Though we do not want to spoil this novel for readers, we will say that in Williams-Garcia’s hands, it is the stubborn clinging to whiteness, and its entanglements with classism, that lead to downfall. Relentless attachments to class and racial hierarchies lead to the greatest disappointments in this novel, since those willing to budge suffer far less.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed