In his keynote address at the 2015 CEE/IFTE conference, Ernest Morrell asked, “What are we doing to help teachers read differently than they were taught to read?” When I heard this question, I reflected on my own high school reading experience which included plenty of dull, round-robin reading from the traditional canon, packets with comprehension questions, and a scarcity of reading for pleasure. It was no wonder that I read very little of what I was assigned.

My experiences align with those of the students in my YA methods course. Upon entering, students confess that they’ve finished very few books since high school. I observe that they lack the stamina required for reading longer texts, “skimming the surface” instead of reading in invested ways. In their journals, few describe an active reading life that includes liking what they read. They describe a love of reading that has long gone dormant. They rarely reference YA literature as part of their reading life. These students--whether they love reading or not--will soon be (or already are) teachers of English.

With the goal of developing a reader identity, our class reads and discusses the rationale and methods for book workshop approaches in Penny Kittle’s Book Love. We think through applications to future classrooms. Then, with the goal of demonstrating that these workshop methods are not only possible, but valuable, in any classroom, we employ a teacher-as-reader model similar to the teacher-as-reader from the National Writing Project, using ideas from Kittle’s book. Staying true to Kittle’s methods, my students let their interests guide their book choices, yet most focus solely on YA literature as they read.

Another well-received routine is our use of Kittle’s “big idea books,” which are basic notebooks individually labeled with a theme such as courage, religion, family, commitment, discovery, etc. Students anonymously freewrite about their chosen theme in relation to what they’ve read recently, adding to voices who have also written about that theme in the same notebook. I save these notebooks from semester to semester as they serve as a testament to the breadth and depth of what my students have read. Big idea books also serve as written book talks for my students, who read their peers’ thematic reflections and often add book titles to their future reading lists.

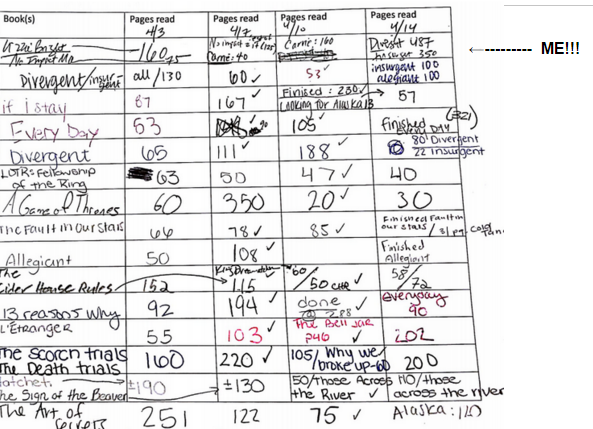

In the midst of these methods, my students monitor their reading ability and track their page counts. I serve as a partner in these efforts, checking their page tallies, conferencing with them regularly, and recommending YA books that I think will interest them. Underlying this approach is a personal investment in workshop: I do everything the students do, writing with them, reading YA literature with them, responding to texts with them. And together, we experience other workshop methods such as close-reading exercises, quotation analyses, literary letters, and speed-dating with books.

Beyond developing a reader identity, students have indicated that they plan to adopt workshop-based mindsets and methods in their future classrooms. One student commented on the role of book recommendations and the community of readers, saying, “...I knew that you were the type of reading teacher that I want to strive to emulate. I want to be able to be at a book store or thrift shop and pick up a book and instantly think of different students’ names who would love to read that particular book.” For another student, who is currently a fifth grade teacher, this workshop approach helped her to understand the value of choice in a reading life. After adopting a workshop in her own classroom, she commented, “When I say that it is time to take out our books for some free choice reading, I hear muffled cheers and see ear to ear smiles….now I have students telling me about their books and dying to get their hands on the books I am reading. I can’t finish books fast enough for them and they can’t wait to shove to the books they are reading into my hands.”

I know that I need to do a longer term qualitative study to lend more credibility to this workshop method. I also know that there are implications for this kind of work in methods courses, like helping preservice and practicing teachers build their libraries (as opposed to solely relying on a few classroom sets) and advocate for themselves when facing administrators and colleagues who insist on less meaningful methods. Aside from future directions, though, I think about how I used to teach YA methods. In the past, I chose all of the texts for my YA methods course and we would read and respond to them together. In many ways, I was doing what Morrell cautioned against, teaching as I had been taught. While I still use some whole-class novels, I now see the value in a workshop model. Having experienced the ways my students’ reading identities, choices and future methods have been impacted, the past is behind me. There is no turning back.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed