| “Literature is not safe. Nor should it be. It is what unsettles us, what allows us to explore things we are afraid to talk about, and it allows us to share dangerous ideas in a safe way." Joan Bertin, Director of the National Coalition Against Censorship |

Incensed at this recall, Bertin remarked,

“No one is saying you should teach a book that isn’t…very good…The problem is once [it’s been published]…pulling it is an extreme act. I’m hesitant to use the word the burning word, but it disappears a book. How do you confront all the issues that people have in their life without feeling a little unsafe?”

So true. Controversial reads have figured a long as the printed work has existed. I had a professor who once remarked that the two single most important inventions were 1) the printing press and 2) indoor plumbing. Safe to say, the world is a far better place for the invention of both.

Joan Bertin

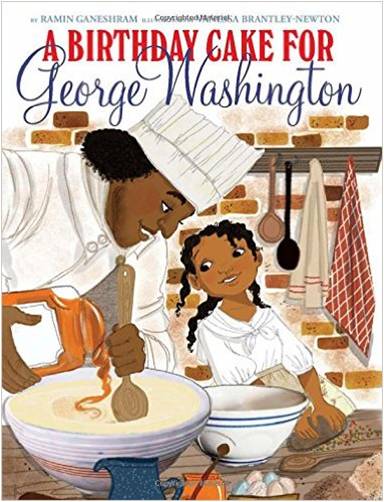

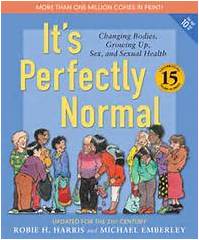

Joan Bertin It’s Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies: Growing Up, Sex and Sexual Health_ (Candlewick, 2014) by Robie H. Harris and illustrated by Michael Emberley, a children’s illustrated picture book which not surprisingly has become one of most banned books of the past two decades. Acclaimed for its frank and honest explanations of bodies, families and sexuality; this cleverly designed, densely packed read is meant to teach children 10 and older about sexual health, emotional health and relationships.

Complete with full-color comically drawn pictures of naked people, this frank and informative read comes fact-checked by medical experts and remains updated. With millions sold, this eye-opening read provides current information about puberty, pregnancy, AIDS, birth control laws, sexual orientation, internet safety, and sexting.

Yet, even in this day and age of changing morays and everything you can imagine on cable and the Internet, this good work brings significant challenges for both teachers and librarians.

"I was warned by several people not to do this book - that it would ruin my career," author Harris said in her remarks at Bank Street. "But I really didn't care. To me it wasn't controversial. It's what every child has a right to know."

No stranger to controversial topics – Kuklin’s two previous reads included No Choirboy (Henry Holt, 2008), about adolescents on death row, and What I Do Now (iUniverse, 2001) about teenage pregnancy – this latest journalistic endeavor has found displeasure from those who feel the topic is unsuitable for classroom discussion and unsupervised reads.

Naturally, Kuklin disagrees. Her motivation for writing Beyond Magenta stems from her awareness that “kids are getting hurt, some getting murdered, and no one has a voice.” For her publisher, Candlewick, as they mentioned at the Bank Street conference, the book proposal was a no-brainer; a groundbreaking concept that has proven its worth in sales and distinction.

Booth says, though, that her books are frequently – what is often called – soft censored. Often, she finds her novels not on the young adult literature shelf, but in the back of the library, reserved for adults seeking ‘street’ or ‘urban’ literature.

“Sometimes,” Booth remarks, “my book is displayed in a glass case during Black History Month….where it can’t be removed.”

Using frank language and portraits of human frailties, Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass, though, has seen more than its share of unamused parents and school administrators. In fact, Medina recalls how she was once disinvited from a public school presentation because of the title of her book alone.

Angered and appalled, Medina fired back a poignant response –

“For me to come to your school and distance myself from my work feels disrespectful of me as an author, but worse, it feels dishonest in dealing with the students, most especially those who are on the receiving end of harassment that already makes them feel ashamed.”

What makes this work controversial, though, is the narrator’s expressed racist attitude toward blacks, Native Americans, and Jews. Much like Huckleberry Finn raises the hackles of those who object to use of the name ‘Nigger Jim’, The Hired Girl is often criticized for its prejudicial content. Yet, as any casual reader can easily recognize, the narrator – an adolescent coming of age at the turn of the century – is not the author, but the voice of a young girl who reflects the prejudices of her time.

Naturally, this book is controversial on several levels – one, illustrating gay teens, and two, portraying Christian righteous behavior. What makes this book unique though is that the author asks readers not to judge its antagonists – the young girls’ aunt and the leaders of the conversion camp – too harshly.

Her objective, as she says, is to provide a full-bodied portrait of how difficult an issue – sexual orientation – is for those who have only known male-female relationships. Thus, Danforth’s intriguing narrative – the coming of out of lesbian teens in the face of a conservative community – has been praised and attacked by both sides of the censorship issue – by those who feel the portrayal of both victim and abusers is too even-handed. And by some, for the topic itself.

That makes our job as advocates – as those who love to read and believe that reading saves lives – even more vigilant and significant.

Our job is to recognize that the printed word is sacred and that we should to do everything possible to make good books available to young people who deserve to learn hard and often, discomforting truths.

Making Joan Bertin’s remarks at Bank Street ever more important - “how do you confront all the issues that people have in their life without feeling a little unsafe?”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed