I have promoted Rich and Sandra works several times. They happen to be a couple of my favorite people in the YA world and I thrilled to talk about their work at the drop of a hat. It has also been my pleasure to present with them a couple of times. My advice, never pass up the opportunity listen to them speak and read everything they write. You can find my post about them here and here.

In today's post, Jeff provides a much better introduction to the fantastic Rita Williams-Garcia than I could provide. Thanks Jeff.

Discussing Rita Williams-Garcia

by Jeff Buchanan

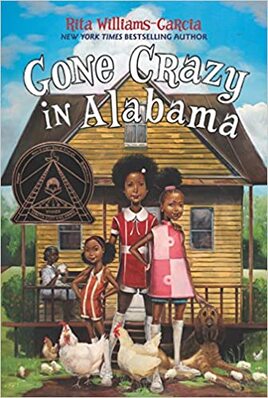

It is the details about family that Rita Williams-Garcia captures so well in Gone Crazy in Alabama, the details that convey an idealized representation

| I read with envy Rita Williams-Garcia’s Gone Crazy in Alabama, admiring the characters whose “voices either followed or lay on top of one another’s” (5), those “sure of [themselves] and speaking [their] mind[s]” (19), and those who would study a family artifact “over and over, to try to learn who [their family] was” (279). There is intimacy, certainty, curiosity in the details composed by Williams-Garcia, values I can agree should be promoted by family. Williams-Garcia makes clear that the Gaithers aren’t an ideal family (although, in a way, they are idealized). They bicker, complain, and carry on; they express disagreement, jealousy, and anger. But there is plenty to admire, too, to hold up as ideal. Delphine says that she “figured when Ma Charles didn’t have a name handy, she called any woman or girl younger than herself ‘daughter’ ” (96). But I don’t believe Delphine has that right. |

I returned crabby, irritable. There had been too many people in the store, too many not social distancing, too many without masks, too many touching the produce. I admit now that I think I got scared, felt real fear about contracting the virus. I felt vulnerable, and I didn’t respond well. I don’t think my reaction was unusual since there’s a great deal of uncertainty and too much we don’t know at the current moment.

Still, that day in the grocery store, all I was sure of was that I wanted to get out of there and not come back. I really don’t know how rational that response was. I’ve been back to the store since and had a better time of it. Yet we don’t know exactly how much risk we’re taking, how exposed we are, how rational we’re acting.

In times of crisis, you just don’t know.

“ ‘Daughter, call your father,’ ” she commands.

The dialogue begins the chapter. Nothing precedes it but the chapter title. It is its own paragraph. Singled out, by itself. And it stands out for the certainty that is its foundation.

Where does this certainty come from? How is Ma Charles so sure about the rightness of this choice and its timing?

The directive—to call your father—is meant for Delphine, the oldest of the Gaither sisters, sisters who have traveled south to spend the summer with their grandmother and great-grandmother. The call back home will end the vacation, will summon the girls’ father to Alabama, will disrupt the routines of two households. But the disruption has already come. Perhaps Ma Charles knows this. The tornado has already altered their lives.

This moment, however, quickly breaks down, as they return from the candy store in chapter one, into squabbling as Delphine and Vonetta disagree over whether Vonetta should fight to get her watch back. But, again, it is the positive aspects at the base of the family that override the interpersonal conflict. As an attempt to de-value the watch and excuse her own lack of assertiveness, Vonetta downplays its function, asking why it’s so special.

“Pa gave it to you. That’s what’s special about your watch,” Delphine notes (3). The watch, itself, isn’t special. The watch is special as gift, as symbol of something special between a father and his daughter. Not only do the Gaither sisters’ parents make clear their love for their children, through gifts and other family routines and rituals, but the sisters recognize these everyday acts as acts of love. The everyday acts of love hold the family together, especially in the face of the conflict they encounter.

The Gaither parents, too, always seem to be easing their daughters into adulthood. Cecile, their absent mother, tells Delphine to look after her sisters (3). And Mrs., their present, step-mother, argues for the appropriate independence of each girl. Delphine doesn’t quite see it that way, explaining that “Capable was one of Mrs.’s words. She used it against me to make me stop helping my sisters. Vonetta is capable of doing her own hair” (4). Mrs.’s instinct is to make sure these girls aren’t dependent, can rely on themselves. She knows that they can’t live forever as a pack of three.

Yet they are three, and they are inseparable. Well on their way to remaining together while exercising independence. There, in the first chapter, Delphine describes how beautifully these three fit, “our voices either followed or lay on top of one another’s for as long as I could remember. We spoke almost like one person, one voice, but each of us saying our own part” (5). Almost like one, but each playing a part. Mrs. reminds them that they are individuals, a fact they will come to fully understand as they grow and mature. But because their family life is grounded in love for one another, in acknowledging the good things each brings to the collective, in celebrating both their common roots and their differences, when they fall into that collective rhythm, when their voices make music together, they do so because it is fun. It is a celebration of who they are, and who they are involves being a daughter and a sister and a Gaither. And that is from where Ma Charles’ certainty comes.

So we decided to go virtual. Could we be sure about the rightness of this choice and its timing?

What guides the Festival is a history born out of love for a daughter who died too early, an essay contest started in Candace Gay’s name. And what blossomed is an event built out of love for reading and writing and the intellectual and academic processes opened up by those activities. We celebrate the feelings and ideas we encounter in books and in lives, we celebrate conversation with one another, and we celebrate our expressions in response.

May 13-15, we are staging a virtual Festival. Join us if you wish (see www.ysuenglishfestival.org). Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace will present and respond to student questions. We’ll do some of our usual activities—trivia, poetry writing, insights sessions, and an awards ceremony. And Rita Williams-Garcia will join us and take student questions. Perhaps someone will ask her about how one can be certain in times of uncertainty.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed