I found out about this WSJ critique from a Facebook post that Rob Bittner shared and commented on. Rob and I have met a couple of times, but we primarily know each other through social media and the fact that we both follow the ebbs and flow of comments on YA Literature that appear on social media. As he lamented this piece and its tone about the “darkness” of YA literature, I decided I better take a look at it.

Much to my surprise, in his WSJ commentary, Mr. Salerno focuses his attention on summarizing the 2018 Summit on the Research and Teaching of Young Adult Literature. This is frankly amazing. I did my best to introduce myself to every attendee. Oh, I might have missed a few people, but not many. To double check, I reviewed the list of paid attendees and guests of the summit. Lo and behold, Mr. Salerno’s name was not on the list. A casual reader of his piece, might assume that Mr. Salerno was there listening and coming to careful conclusions after interviewing some of the authors and academics like Alice Hayes (Alice has commented that she wasn’t interview by this individual) and James Blasingame. Well, that doesn’t seem to be the case. It appears that the information was likely lifted from one of these two articles (First, one reporting on the participation of academics from Arizona State University or second from University of Nevada, Las Vegas that summarized the summit.) or perhaps a combination of both.

In reality, the Summit was invigorating. Participants left with new pedagogical ideas, lists of books that covered a range of topics, new friendships, and partnerships that will lead to new research. Below you will find responses from a several of the Summit participants—participants who actually attended. These responses have appeared on Facebook and other venues, but I felt they need to be collected and archived. Below, you will hear from Chris Crutcher, Kelsey Clause, Amanda Melilli, Kia Richmond, Stephanie Toliver, and Louise Freeman.

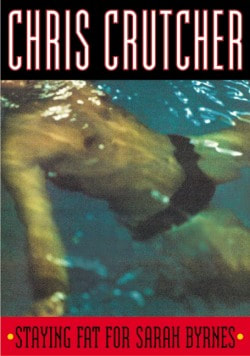

From Chris Crutcher

I kinda hafta respond to Steve Salerno’s article in the Wall Street Journal entitled “The Unbearable Darkness of Young Adult Literature.” I put the link up here, but WSJ may require you to subscribe in order to read it in its entirety, and unless there’s a lot else you want to read in the Journal, spend your hard-earned money where it will do you some good. Quick synopsis: Salerno critiques the recent “Summit on the Research and Teaching of Young Adult Literature” held at the University of Las Vegas this past summer, in which Kekla Magoon (has there EVER been an author in any genre with a cooler name?), Laurie Halse Anderson and I participated. Mr. Salerno proposes that good YA lit should inspire and that the dark stories (represented in this case, by the three of us) not only don’t inspire but may in fact add to rates of suicidal thought and depression among our youth. Salerno states, “It is difficult to understand why educators would so determinedly insist on immersing students in an unsavory worldview, portraying life in terms of its anomalies and unorthodoxies, as if there’s something wrong with you if there’s nothing wrong with you.” First, Steve - and I mean this in the gentlest way - if you’re writing about Young Adult Literature for the Wall Street Journal, don’t call your mom; this doesn’t HAVE to be the pinnacle of your career. Second, third and fourth and however many it takes me to get through this, it might serve you to spend a little time in public schools and with teachers, counselors and social service workers; and with KIDS, before you weigh in on the value of literature written about them, or what may or may not inspire them. Kekla’s “How It Went Down” - told from 18 different points of view of a circumstance in which a young black boy, who may or may not have been armed, is shot by a white man, who may or may not have had a racial motive - is as good a depiction of the DILEMMA we face in a culture in which young black men are being gunned down at an alarming rate by shooters who seldom face consequences for that action. You couldn’t FIND a better piece to “inspire” students to engage in that debate on a level playing field. Laurie’s autobiographical account of not only surviving a young life scarred by sexual abuse and existence with a brilliant, raging, loving, highly flawed alcoholic father, doesn’t depict an “unsavory world view,” but rather the world view of a girl who, having endured ruggedly harsh circumstances, uses those circumstances as a springboard to SOAR as she grows and understands and rejects victimhood. Steve, she’s Laurie Halse Anderson, for Chrissake; a MODEL for girls - and boys - who have at any time felt marginalized by their life circumstances, or by derision in the eyes of their peers. Hell, you might even call her an “inspiration.” Or at least I might. Should you take time away from your computer screen to actually visit a public school classroom, Steve, you will find yourself among one-in-three girls who have been in a significant way, sexually mistreated; one-in-six boys. Others will be living in homes exhausted by addiction. Others will be dealing with personality structures that invite mockery from their classmates. You won’t know who most of them are, however, because their best survival skill is control of their secret. Some will appear to be high achieving, model students, others will confound you with their confrontational behavior. You will be confounded because You. Simply. Don’t. Get it. The remainder of students in the class, those you describe as untraumatized, know these kids; share six hours a day with them. Stories that depict what you call “an unsavory world view” allow bruised kids to talk about - and therefore better understand - their own situations, and relatively unbruised kids to become more enlightened, and therefore, hopefully, more decent. Steve, I get it that you like stories where the dog dies and the kid learns about the circle of life, or where the goofy kid gets the girl when his hidden talents are revealed; hell, I like those stories too, and they’re valuable. But before you bring your judgmental bullshit to bear on the all-star group of educators who brought that summit together, and the educators who walked away from it charged up; you might want to spend a little time talking with THEM, or those of us who write, or the relatively healthy kids you think you’re representing, who ALSO send us thank-you letters for writing about hazardous adolescent struggle. Chris Crutcher |

From Kelsey Claus

I got bogged down reading the comments of the folks that applauded Salerno for his worldview. Lucky for most of them, they, and their children, haven't experienced most of what gets discussed in the YA lit that's "unsavory"... But that doesn't mean it's not happening to SOMEONE. I'll never understand how people think putting blinders on and ignoring the fact that there are youth dealing with adult-sized issues solves anything.

I'm not going to get too worked up because it is the Wall Street Journal after all... Not a lot of minds you're going to be changing there.

This close-minded article showcases the impact of the work you and your colleagues can have... There's clearly a section of the next generation who aren't going to learn empathy at home. Thank goodness for YA Lit to fill that gap.

Maybe we'll extend a personal invitation to Salerno to attend the next Summit and expand his perspective.

Kelsey Claus

From Amanda Melilli

However, there is also something scary about this opinion article that drives me nuts as a librarian: the author didn't accurately represent the entire Summit. In fact, he didn't even accurately represent all of the main authors that presented there; he left out Bill Konigsberg who had just as much time and presence at the conference as Laurie, Chris and Kekla. But Bill and his works don't match the argument he was trying to make, so he wasn't mentioned in the article.

Was there some pretty heavy, dark stuff addressed at the Summit? Yes, but that wasn't the ENTIRE summit as the opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal makes it sound like. There were presentations on a huge range of topics (found here: http://www.yawednesday.com/2018-summit.html) including my own that included Light Novels. That's right. Light Novels. You know, those quirky novels from Japan where it's not uncommon for main characters to wake up as vending machines or spiders in some fantasy video game type land? A far cry from the works of Chris, Laurie, Kekla, and Bill, but we had conversations about these types of books as well!

In fact, all of the teachers I have met with since the Summit have been asking for help in finding one type of reading material for their classrooms: engaging works that their students will actually read and have complex conversations about. THAT's what I see that our educators got from the Summit. Not some need to shove trauma down their students throats, but a desperate need to find materials that their students can relate to and that makes them want to read more.

The Summit was all about helping educators get their students engaged with the ELA curriculum whether through books dealing with trauma or the fantastic or graphic novels or short stories, and the WSJ article is a gross misrepresentation of the conversations and learning that actually took place there.

We're really excited for the next Summit!

From Kia Richmond

I wish that Steve Salerno would have actually attended the Summit on the Research and Teaching of Young Adult Literature at the University of Nevada - Las Vegas (organized by Steven T Bickmore) with us in June 2018. Perhaps he would have gotten some of his facts right before casting aspersions on educators, authors, and the youth of America.

I am one of the “nearly 50 presenters—top educators and authors from across the land” that Salerno speaks of in his Wall Street Journal essay (“The Unbearable Darkness of Young Adult Literature,” August 18, 2018). Thanks to a research grant and sabbatical from Northern Michigan University, I was proud to attend the Summit, at which shared some of the results of my recent research on mental illness in 21st century young adult literature.

In this presentation, I focused on 2 of the 30 contemporary young adult texts I analyze in my forthcoming book, Mental Illness in Young Adult Literature: Exploring Struggles through Fictional Characters (ABC-CLIO/Greenwood Press): Wintergirls and The Impossible Knife of Memory (both outstanding examples of young adult literature by Summit attendee and author Laurie Halse Anderson). Session attendees were led through a close reading activity focused on characters’ use of stereotypical language related to mental illness (e.g., “freak, zombie, crazy, unstuck in time” in The Impossible Knife of Memory and “skin-bag of a girl, locked up, crazy seeds, circus freak” in Wintergirls) as well as Anderson’s use of authentic terminology (e.g., “catastrophizing, worry, fear, nightmares, fatigue, therapist” in Wintergirls, and “disordered behavior, therapy, Boerhaave’s syndrome, malnourishment, disturbed brain chemistry, psychiatric care facility” in The Impossible Knife of Memory).

Discussions following the activity centered on the benefits of examining assumptions underlying the language used by characters (and, by extension, real people). This kind of lesson dovetails with several objectives in the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and can help students to consider how stereotyping language is connected to biased attitudes and can, when left unchecked, lead to other discriminatory behavior (as described in the Anti-Defamation League’s “Pyramid of Hate”). Helping young adults think about the language they read – and use – can empower them and perhaps help them make informed choices about their behavior toward others.

In designing such a presentation (and teaching a similar lesson in my Good Books class this summer at NMU), I was not assuming that “all students arrive at school traumatized in some fashion” as Salerno claims that I (and other Summit presenters) did. Nor was I “determinedly insist[ing] on immersing students in an unsavory worldview, portraying life in terms of its anomalies and unorthodoxies” as Salerno states in his essay.

My goal in talking about Wintergirls and The Impossible Knife of Memory was to offer Summit attendees the chance to discuss how young adult literature can, as Michael Cart says, help teen readers see themselves on the pages of the books, foster “under¬standing, empathy, and compassion by offering vividly realized portraits of the lives—exterior and interior—of individuals who are unlike the reader,” to tell young adults “the truth,” even when it is unpleasant.

I agree with Summit presenter and young adult author Chris Crutcher (who, unlike Salerno, actually has experience in the mental health field as a child and family therapist, and who, unlike Salerno, actually has experience as a secondary teacher). Chris says that stories like his and Anderson’s (featured in sessions such as mine at the Summit), “allow bruised kids to talk about - and therefore better understand - their own situations, and relatively unbruised kids to become more enlightened, and therefore, hopefully, more decent.” Creating more empathetic and informed citizens is part of the work of English language arts teachers, who are charged in the CCSS with helping youth to develop “critical-thinking skills and the ability to closely and attentively read texts in a way that will help them understand and enjoy complex works of literature.”

Salerno asks whether higher rates of depression and suicide are “an organic outgrowth of life’s legitimate trials—or are […] a crisis manufactured, at least in part, by painting life as so much more trying than it is?” It is disappointing that an experienced journalist (and visiting lecturer at UNLV) has to resort to using a faulty method of reasoning (either-or thinking) in his writing. The American Psychiatric Association reports the prevalence of childhood trauma (e.g., physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; violence; war; disasters; etc.) as very high, with more than 65 percent of children experiencing trauma by age 16. Moreover, the National Institute of Mental Health estimates that more than 20 percent of young adults experience serious mental illness. It doesn’t seem reasonable that these rates are the result of a manufactured crisis nor to life being painted as “more trying than it is.”

In his last paragraph, Salerno says that if Summit attendees did indeed “care about young adults and their growth,” as Summit presenter Alice Hays states, then we should “consider recommending books that make the world sound like a more hospitable place to be.” Rudine Sims Bishop argues that literature can act as a window, sliding glass door, or a mirror, showing readers more about their own worlds and lives or the lives of others that might be “real or imagined, familiar or strange.”

The Summit in Las Vegas provided attendees with opportunities to discuss young adult literature of all kinds: sports literature (Alan Brown), science fiction (S.R. Toliver), graphic novels (Dani Kachorsky and Stephanie Reid); historical fiction (Sharon Kane and Ritu Radhakrishnan; and Diane Scrofano Novoa – who even connected YA lit to the musical Hamilton); as well as that connected to bullying (Amanda Melilli), social justice issues (Trista Owczarzak; Rebecca Maldonado, Crag Hill, and Danetra King; Tiye Cort; and Laura Davis), and mental illnesses such as PTSD (Louise Freeman Davis – and myself), substance use (Rachel Rickard Rebellino, Caitlin Murphy, and Karly Marie Grice), and eating disorders (me again).

Salerno’s piece asks why Summit attendees didn’t focus on “something other than darkness and depravity." However, it does not address the fullness of context of the Summit, which DID include sessions on light and humor and love and relationship as well as mental illness and bullying. Nor does it bother to mention how talking about young adult literature better prepared attendees to reenter their lives as more informed, empathetic educators, librarians, and advocates for youth, which might just make the lives of young adults that much better. Wow, after reading his piece, I was hoping for happily-ever-after. Too bad Salerno didn’t deliver.

By Kia Richmond

From Stephanie Toliver

| Stephanie was one of the presenters and contributor to this blog in the past. She responded to the WSJ piece quickly. In a couple of days she had a piece published in Blavity. Stephanie entitled her commentary "The Unbearable Darkness of White Privilege and Why The Wall Street Journal Needs to Leave Our Literature Alone". Stephanie, like the others who commented in response to the misguided piece was in attendance. Her expertise as a participant, a scholar, and attendee, surpasses any hint at expertise that Mr. Salerno pretends to have about a literature that he clearly doesn't read or know much about. Please take a few minutes to follow Stephanie's argument. |

From Louise Freeman

In his recent editorial, Mr. Salerno asserts , “Classroom discussions that celebrate this or that fictive martyr, tragic figure, antihero or other outlier are bound to create more outliers: Consciously or not, adolescents will seek membership in the group that appears to be getting all the attention.” He goes on to ask: “And if indeed it is psychologically debilitating for the young people depicted in today’s YA literature to inhabit a world of virulent racism and interminable bullying and sexual abuse, then why make the vast majority of students, who don’t live amid such conditions, feel as if they do?... Are high rates of depression and suicide an organic outgrowth of life’s legitimate trials—or are they a crisis manufactured, at least in part, by painting life as so much more trying than it is?”

Mr. Salerno is apparently unaware of the many psychology studies in recent years that have elucidated the role of fiction in our lives. According to many researchers: Kidd, Mar, Oatley, Vezzali and others (see list below), fiction plays an important role in enhancing empathy, understanding of others and psychological well-being. True, the effects of fiction on adolescents have not been studied to the same extent as those on adults. However, much of the research has been on college-aged students, only a few years older that the target audience of authors Magoon, Crutcher and Anderson, whose work Mr. Salerno criticizes as excessively “trying” and full of “darkness and depravity.”

Why expose young people to the “unsavory worldviews” of “outliers” in books? The answer is, quite simply, to build empathy. The minority of students who encountered such hardships in their lives can realize they are not alone. The majority of students, who have been more fortunate, benefit from simulated social contact with the characters, as they “meet” them in a safe environment. Research has shown such contact mimics the effects of encountering a similar person in real life, but in a much safer context. There is every reason to believe that reading and discussing fictional “outliers” with “unsavory worldviews” creates not more outliers, as Mr. Salerno speculates, but students with more compassion for outliers.

Consider one example: a series of studies 6th grade teacher Martha Guarisco and I conducted. We administered tests for empathy and theory of mind--- the ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others—before and after a novel unit. After reading R.J. Palacio’s Wonder, students reported higher levels of perspective-taking, and improved ability to recognize social situations that could hurt others’ feelings. After reading Kwame Alexander’s The Crossover, students expressed higher levels of empathic concern for others, and at least some subsets of students had improved ability to discern faux pas and to recognize emotions from facial expressions. It is true that neither of these books is as “dark” as the works of Magoon, Crutcher and Anderson; but, they are also targeted towards much younger children. And they do not shy away from uncomfortable topics. The 10-year-old protagonist of Wonder has severe facial deformities that isolate him and lead to bullying not only by children, but by adults; a mother of one of his classmates tries to have him removed from his school and, when that fails, arranges to have him airbrushed from the class picture. Josh, of The Crossover, physically attacks his twin brother in a fit of jealousy, and later sees his father die of a heart attack. These are not necessarily “uplifting” or “comforting” topics.

Yet, the students’ teacher was able to see empathy in action. Remarkably, several of the students-- from an expensive, predominantly White private school in the deep South, did not realize the protagonists of The Crossover were Black, and therefore missed the significance of a key scene, where Josh sees his father being pulled over by a police officer and becomes afraid that even his father’s fame as a basketball star may not save him from a How It Went Down situation. According to Ms. Guarisco, once the story was explained to them, the students left that classroom discussion not full of fear that the world is full of corrupt police ready to gun down the unarmed and innocent, but with compassion for a worldview they had never before considered.

Would similar empathy-enhancing effects be seen with the works of Crutcher, Magoon and Anderson? That research has not been done, though a group of the scholars that convened at the Las Vegas meeting left with plans for research projects to investigate the effects of young adult literature more directly. As a longtime professor of psychology and a fan of quality young adult literature, I am eager to assist. And, the authors who attended were equally supportive of such research endeavors.

Perhaps Mr. Salerno, like Julian’s mom in Wonder, would prefer to airbrush any theme that depicts a world as less than “hospitable” from student reading assignments. But there is zero evidence that students would be mentally healthier as a result. On the contrary, fiction that engages students and transports them into an unfamiliar world—even if that world is sometimes dark and depraved,—appears to promote social cognition, empathy and understanding.

Appel, M. (2011). A story about a stupid person can make you act stupid (or smart): Behavioral assimilation (and contrast) as narrative impact. Media Psychology, 14(2), 144-167.

Djikic, M., & Oatley, K. (2014). The art in fiction: From indirect communication to changes of the self. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(4), 498.

Djikic, M., Oatley, K., & Moldoveanu, M. C. (2013). Reading other minds: Effects of literature on empathy. Scientific Study of Literature, 3(1), 28-47.

Fong, K., Mullin, J. B., & Mar, R. A. (2013). What you read matters: The role of fiction genre in predicting interpersonal sensitivity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(4), 370.

Freeman, L., & Guarisco, M. (2015). The Wonder of empathy: Using Palacio’s novel to teach perspective-taking. The ALAN Review, 43 (1): 56-68., 43(1), 56-68.

Gabriel, S., & Young, A. F. (2011). Becoming a vampire without being bitten: The narrative collective-assimilation hypothesis. Psychological Science, 22(8), 990-994.

Guarisco, M. S., Brooks, C., & Freeman, L. M. (2017). Reading Books and Reading Minds: Differential Effects of Wonder and The Crossover on Empathy and Theory of Mind. Study and Scrutiny: Research on Young Adult Literature, 2(2), 24-54.

Johnson, D. R. (2012). Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behavior, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 150-155.

Johnson, D. R., Jasper, D. M., Griffin, S., & Huffman, B. L. (2013). Reading narrative fiction reduces Arab-Muslim prejudice and offers a safe haven from intergroup anxiety. Social Cognition, 31(5), 578-598.

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342(6156), 377-380

Mar, R. A., & Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspectives on psychological science, 3(3), 173-192.

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., dela Paz, J., & Peterson, J. B. (2006). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. Journal of research in personality, 40(5), 694-712.

Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., Giovannini, D., Capozza, D., & Trifiletti, E. (2015). The greatest magic of Harry Potter: Reducing prejudice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(2), 105-121.

Final Comments by Dr. Bickmore

I hosted the conference and Mr. Salerno works at my University, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. I am not that hard to find. He could have visited with and even shared his bleak take on Young Adult Literature. We could have had a conversation. It could have quoted me directly instead of lifting quotes from Alice Hayes or James Blasingame from a report of the summit--that by the way was written by someone who attended.

Oh, Mr. Salerno, if you were there and I missed you, you owe the Summit 175 dollars.

Until next week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed