In all honesty, I long thought myself a culturally responsive teacher because Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was in my classroom library, and I kicked off my poetry unit with Langston Hughes. But like all teachers, I am a work in progress. My first “woke” moment came courtesy of Matt de la Pena, who shared his interpretation of something he’d heard Junat Diaz point out about monsters in comic books: they can’t see themselves in mirrors. When we don’t give our students reflections of themselves in literature, are we playing a part in creating those monsters? I may have been offering “multicultural” texts, but there was definitely a shortage of mirrors in my classroom.

| What’s a mirror for some may be a window to others. One excuse I might have offered for not seeking out diverse texts is that my school setting is fairly homogenous. Because of some collaborative work with Dr. Louise Freeman (you can read about that here), however, I came to the understanding that by not paying attention to the windows I was offering, I was depriving students. Our project measured changes in students’ empathy before and after reading R.J. Palacio’s Wonder. To summarize psychologists’ work in this field, literature gives students a kind of vicarious experience with people different from them. What’s particularly exciting to me as a teacher (and reader) is that this vicarious empathy extends itself to real life; it sticks. By giving students windows into the lives of others, I could be helping them not just to expand their worldview, but also to be more empathetic in general. |

Conversations about race, class, and gender bias aren’t easy to have with middle school students, but they are incredibly important. Students are surrounded by examples of how not to have these discussions: shouted soundbites, gross generalizations, disrespectful discourse.

When we shy away from difficult topics, we are covering literature’s windows with blackout shades. These conversations remain difficult, but the following strategies help:

- Preface the conversation with honest disclosure: This might feel uncomfortable because we are taught not to talk about these things, but it’s important for us to do so.

- Bring in reinforcement: This school year, when I addressed depression and suicide in K. Alexander’s Booked, I invited our guidance counselor to teach a mini-lesson on healthy coping and available resources.

- Give time for writing: Writing helps us process difficult concepts, sort out our thoughts, and pose questions.

Like most teachers, I have multiple initiatives vying for my time and attention: Project Based Learning, tech integration, non-negotiable skills. By the end of the year, I feel like Jessie Spano on caffeine pills. There’s never enough time!

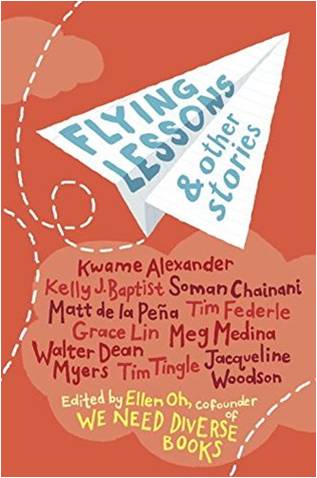

Which is why I nearly wept with gratitude when Flying Lessons & other stories came to fruition. Middle grade? Check. Short stories? Check. Windows and mirrors? Check.

My city experienced devastating flooding this school year, beginning on what was to be the first day of school. Although we adjusted our schedule to make up some lost minutes, I’ve had that constant feeling of being “behind.” I wanted to read another novel with students. I wanted to spend more time on verbs. I wanted to give time to more voices, more stories.

Flying Lessons & other stories, an anthology that grew from We Need Diverse Books, features stories from authors my students know and love. At the end of the short story by Soman Chainani from which the anthology draws its title, Nani issues this truth to her grandson: “All of us deserve something to look forward to.” Students can look forward to beautifully crafted stories written for them, and I can look forward to giving them a few more reflections of themselves and windows into the world around them.

Even as this school year winds down, I’m thinking ahead to the writing lessons I’ll plan based around Flying Lessons & other stories. Any one of the stories in the anthology could be explored in a stand-alone way to highlight the author’s craft.

Grace Lin’s “The Difficult Path” packs powerful verbs, similes, and passages that show, rather than tell, into just a few pages. Kelly J. Baptist’s “Red Beans and Rice Chronicles of Isaiah Dunn” is full of personification. “Choctaw Big Foot, Midnight in the Mountains” by Tim Tingle and “Seventy-Six Dollars and Forty-Nine Cents” by K. Alexander feature effective repetition.

| Essential Questions to Use with Flying Lessons & other stories No way am I waiting until next school year, though, to share these stories with my readers. Because of our time crunch, I’ve designed a mini-inquiry unit for my 6th graders this May. We’ll start our short story unit with four essential questions in mind:

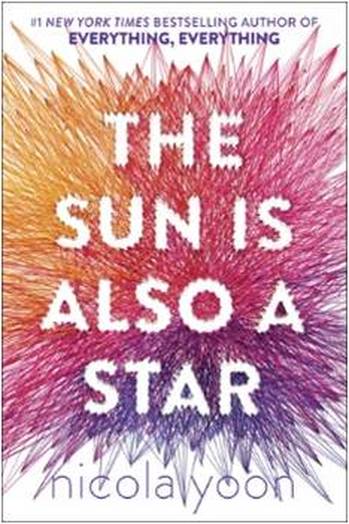

After they become friends, Celeste tells Treetop not to touch her hair. “I’m not a dog to be petted!” There’s a wonderful chapter of Nicola Yoon’s The Sun Is Also a Star dedicated to the topic of black hair, and I plan to pull this in as a discussion starter. |

Grace Lin’s “The Difficult Path” does: “When I was sold to the Li family, my mother let Mrs. Li take me only after she’d promised that I would be taught to read.” Why was the narrator sold? When does this story take place?

Meg Medina’s “Sol Painting, Inc.” will also have readers asking questions from the very beginning. “I reach inside the window of Papi’s van and yank on the handle to open the passenger door. It’s my turn to ride in front. Roli sat there last time.” Who are these people? Where are they going?

My favorite opener in the entire anthology belongs to “Choctaw Bigfoot, Midnight in the Mountains” by Tim Tingle. “Blame my uncle Kenneth. Everybody else does.” Who doesn’t have a family member worthy of blame?

Students will choose one of the stories to explore in small groups and later choose from several different ways to present it to the whole class. Based on those presentations, students will choose a third story to read independently.

As a culminating assessment, students will create something--a Padlet, a Prezi, a formal essay, a letter, really any communication strategy could work here-- to demonstrate their understanding of how at least three of the stories address one of the essential questions.

Reach out to me on Twitter at @marthastickle or shoot me an email: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed