René Saldaña, is one of those people. We have know each other for over a decade, but always have stories to share and tales to tell. In fact, I appreciate his perspective so much that we presented together at NCTE in 2019 and had planned to do it again in 2020, but alas, the best laid plans.... I was very happy that he took the opportunity to submit a proposal for the blog. Once again, I have more books on my "to be read" list. Thanks again, my friend.

Hey, That’s Me In A Book: Ain’t That Something!

René Saldaña, Jr.

Those of us from here say we live in the RGV, short for the Rio Grande Valley of deep South Texas. Those of us slightly older use the term Vallucos to refer to ourselves: “Soy Valluco” (“I am from the Valley”). The older and more proper generation might say, “Soy de El Valle.”

This is the same Texas-Mexico border region that gave us Américo Paredes, folklorist, historian and novelist, who wrote about the border towns of Brownsville and Matamoros in his novel George Washington Gómez. The rushing and winding waters of the Rio Grande, as it is called in the U.S., the Río Bravo as it is called by Mexicans and many of us who grew up here, empties into the Gulf of Mexico not far beyond Brownsville.

It also gave us Rolando Hinojosa Smith, a novelist whose work has been compared to Faulkner’s. Hinojosa is better, though. His Estampas del Valle tells about the RGV in Spanish. Enough said.

| Gloria Anzaldúa is also from the Valley, the nearly 125 mile stretch which she describes as “una herida abierta,” an open wound (25). In her life, she was not well-regarded here. She was too radical for our more traditional modos or ways, resulting in the wound, deep and painful to her as she documents in her seminal work, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, in which she also draws attention to the Valley’s very own self-inflicted wound, deeper and jagged and festering still. She died in 2004 and is buried back in the RGV. The majority of people living here are Mexican American or Mexican (between 90-95%, depending on the source). We grow up speaking Spanish and English, for many of us simultaneously, and we also speak a third language, Mestizaje, which is not Tex-Mex, Spanglish, or bilingualism. It is a hybrid tongue. |

It is a magical place. A land of in-between: two borders, two languages, two cultures. Soy ni de aqui, ni de alla. This is where I grew up. This is where I’m from. This is where I write about. Soy Valluco.

You would think that with so many of us brown-skinned living here and so many well-regarded brown writers from here that our required reading lists would reflect people and place. You would think. But you’d be wrong.

In addition to Paredes, Hinojosa, and Anzaldúa, there is Jovita Gonzalez (born in 1904 in Roma, Texas, on the westernmost part of the RGV, which is the entry-point for me when I travel to Mier) and Genaro Gonzalez whose Rainbow’s End tells of three generations of a South Texas family. Writing for children and adolescents are David Rice (Give the Pig a Chance and Crazy Loco), David Bowles (They Call Me Guëro and The Smoking Mirror), Viola Canales (Orange Candy Slices and Tequila Worm), Xavier Garza (Lucha Libre: The Man in the Silver Mask and Creepy Creatures and Other Cucuys), myself (The Jumping Tree and A Good Long Way), Daniel Garcia Ordaz (his book of poems Cenzontle/Mockingbird deals with much of this and more), and Ruben Degollado (Throw).

There are many more titles we’ve published. More writers I’ve left off the list. Apologies to them.

Home, like many points beyond and farther north of Falfurrias, is only now beginning to place value on a child’s funds of knowledge (Moll, Neff, and Gonzalez) and make use of them to enrich their reading experiences. And the movement is at a snail’s pace, taking its sweet time, but time’s not a commodity we’ve got much of.

I haven’t always loved reading. I’ve written about this before in other places: how the moment I started junior high, we stopped reading and instead did Literature[1]. The earliest story I can remember is de Maupassant’s “The Necklace.” I didn’t understand why I should care about a woman who wanted to go to a ball, dress beyond her means, including borrowing a fancy necklace, only to lose it, etc. We read O. Henry. Bradbury’s stories “The Veldt” and “All Summer in a Day” I liked most, and Theodore Thomas’s “The Test,” which is not to mean I liked them enough to say I loved reading again.

None of these stories mattered to me personally-speaking. That is what reading should cause in a kid: a reaction. A kid should read a book and say, “Aha, that’s why I read that book and why I’ll always remember it: it tells the story of ME.”

[1] I document this experience in an upcoming issue of Study and Scrutiny in my article called “On Becoming a Life-Long Reader, and How I Almost Blew It as a Teacher: An Extended Testimonio” and in another article titled

"Mexican American YA Lit: Literature with a Capital 'L'" published in The ALAN Review, Winter 2012 issue.

| For me, it was Piri Thomas’ Stories from El Barrio. I found it by chance on the shelf of my junior high library. In it, the characters are named Pedro and Johnny Cruz who speak Spanish like I did with my friends strutting down hallways between classes. In one story, “The Konk,” Piri, the young narrator, tells about wanting to get a konk, a hair-straightening treatment that burns his scalp, and at home when his parents ask what he’s “done to your beautiful hair” (50), he says it was because he was tired of being different (50). That I got. That was me. |

This realization was my herida abierta. I knew that there was at least one book that told my story, but if I had not stumbled upon it, I would never have known even that. I began wondering why we weren’t being made to read Thomas in class? If I liked it, I was sure others would, too. It would have made a difference for me and them—a teacher, who I took to be the sole authority figure in the classroom, intentionally selecting my story as the one to assign would have been big: I mean, everyone reading my story on the pages of this book, everyone reading me/us!—of course it would have made a difference.

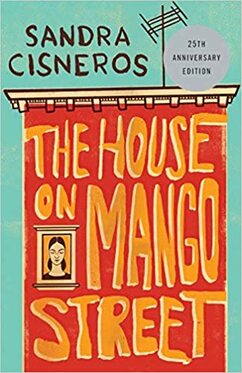

| Desgraciadamente, it would be another 10 or so years before I discovered myself on the pages of another book. This one was Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street. I was not a tweenaged Mexican girl growing up on the south side of Chicago named Esperanza Cordero. I was a graduate student working on a masters in literature. A young man from a small ranchito in deep South Texas with the Río Bravo flowing only a few miles from my backyard. But Esperanza’s was my own cuento. Reading that book, I knew there had to be more. By then, I had a voice and knew how to use it: so I asked, “Where are my books?” Soon after, the flood gates opened. I found Anaya, Denise Chávez, Ana Castillo, Gloria Anzaldúa, Dagoberto Gilb, and so many more. But even when I was in front of my very own high school classroom, that sole authority figure, I opted for the required reading list: Bradbury, Hemingway, Fitzgerald. Why? To this day, it is the one thing I regret most from my teaching days. Would that I could go back, but I can’t. |

Desgraciadamente, though there are more stories about brown kids being published yearly, and though there are more teachers today than in my day introducing these brown stories to their classrooms, it is still not enough.

A shelf of these titles set apart in a library for these kids is not enough.

September set apart for all of us browns is not enough.

Much less so, literacy by chance.

I dream of that day when brown kids walk into a school library or a literature classroom and find themselves surrounded by all those books reflecting them and be able to say, in Esperanza’s words: “All brown all around, we are safe” (28).

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 3rd. ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2007.

Bishop, Rudine S. (1990). “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.” Perspectives: Choosing

and Using Books for the Classroom, vol. 6, no. 3, 1990. Accessed from https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

Cisneros, Sandra. House on Mango Street. Vintage Books, 1987.

Moll, L.C., Amanti, C., Neff, D. & Gonzalez, N. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory Into Practice, vol. 31, no. 2, 1992, pp. 132-141.

Thomas, Piri. Stories from El Barrio. Alfred A. Knopf, 1978.

References

Bowles, David. The Smoking Mirror. IFWG Publishing, 2016.

---. They Call Me Güero. Cinco Puntos P, 2018.

Canales, Viola. Orange Candy Slices and Other Secret Tales. Piñata Books, 2001.

---. Tequila Worm. Wendy Lamb Books, 2007.

Degollado, Ruben. Throw. Slant, 2019.

Garcia Ordaz, Daniel. Cenzontle/Mockingbird. El Zarape Press, 2018.

Garza, Xavier. Creepy Creatures and Other Cucuys. Piñata Books, 2004.

---. Lucha Libre: The Man in the Silver Mask: A Bilingual Cuento. Cinco Puntos P, 2005.

Gonzalez, Genaro. Rainbow’s End. Arte Público P, 1988.

Hinojosa Smith, Rolando. Estampas del Valle. Bilingual Review P, 1992.

Paredes, Américo. George Washington Gómez. Arte Público P, 1990.

Rice, David. Crazy Loco. Dial, 2001.

---. Give the Pig a Chance. Bilingual Review P, 1996.

Saldaña, Jr., René. A Good Long Way. Piñata Books, 2010.

---. The Jumping Tree. Delacorte Books for Young Readers, 2001.

| René Saldaña, Jr. is an associate professor of Language, Diversity & Literacy Studies at a university in West Texas. He is the author of the YA novels The Jumping Tree, The Whole Sky Full of Stars, and A Good Long Way, among others. He is currently working on his literacy memoir in verse, tentatively titled Eventually, Inevitably: My Writing Life in Verse. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed