| We are pleased to welcome Dr. Celeste Trimble to YA Wednesday today. She suggests that we use Indigenous YA literature as part of teacher education programs. I will be taking her advice to heart for this coming academic year as I teach Firekeeper's Daughter. Dr. Trimble is an artist, a writer, and an Assistant Professor of Literacy at Saint Martin’s University in Washington State. She specializes in Indigenous literature for youth, queer literature for youth, and the intersections of book culture, youth culture, and the arts. |

In 2005, Washington passed legislation in which the language used merely “encouraged” schools to adopt the free and easily accessible STI curriculum, which was vetted by all federally recognized tribal nations in the state. When the state realized that this encouragement was not sufficient enough to motivate most schools and districts to adopt the curriculum, legislation was passed in 2015 changing the word “encouraged” to “must,” making STI mandatory. However, teachers were not prepared to teach about tribal sovereignty, so in 2018 legislation passed requiring teacher education programs to incorporate STI into their courses.

Even though STI is now mandatory in all K-12 schools and teacher education programs in Washington, it is still not fully implemented in all grade levels across the state. Partially, this is because the financial burden for implementing STI, including supporting teacher training, has fallen on individual districts and tribal nations that are ill equipped to fund it. Partially it is because in the original language, districts weren’t required to adopt it until they adopted a new Social Studies curriculum, although that has since changed. It is possible that teachers, overburdened by more and more material that needs to be “covered,” feel they cannot fit anything else in, although the creators of STI designed the base level of the curriculum to only necessitate a very small time commitment in order to ease this particular struggle. Most likely there are other reasons, too.

But I suspect that the primary reason the Since Time Immemorial Tribal Sovereignty Curriculum hasn’t been enthusiastically adopted is because the majority of adults responsible for making curricular decision in classrooms, schools, and districts do not understand why it is important, do not feel the deep significance and necessity of learning about the past and present of the Indigenous peoples of this land. This is most likely because they never learned about Indigenous history, law, and culture in their own K-12 and higher education experiences either. This is a cycle of erasure and miseducation, and I believe, through my own experiences with students, that reading Indigenous youth literature is one way to begin to break this cycle.

I am a professor in a teacher education program and teach courses in other departments around campus as well. It is both a delight and an intentional form of activism to include Indigenous authored texts on every reading list. Consistently, students tell me they have never read a book by a Native author before. Additionally, as students begin to realize their lack of knowledge of Indigenous history and culture, they share stories from their own K-12 educational experiences of the erasure of Native voices and histories, as well as the experiences of outright miseducation they have endured. Of course, there are sometimes exceptions, students who had that one teacher who did engage critically with Indigenous histories, cultures, and texts in their classrooms. This shouldn’t be the exception, though.

When we read books for youth written by Indigenous authors within the college classroom, the preservice teachers in my classes (predominantly but not exclusively white and female) feel a shift occur. Instead of seeing the Since Time Immemorial tribal sovereignty curriculum as another mandatory set of standards to get through, they begin to wonder how their understanding of this country would be different if they had read these books and had these conversations during their own K-12 years. At midterms, students invariably say, “Why didn’t I know this?” They feel betrayed by their own educations. By the end of semester reflections, the most common refrain is, “I’m so excited to bring these books and this curriculum into my future classroom so my students are not as unaware as I was.” Preservice teachers develop not only the beginning of an understanding of the histories and stories that weren’t given access to in school, but they also develop a desire to make sure Indigenous erasure and miseducation does not occur in their own classrooms. Both of these things are necessary for a successful implementation of STI or other state Indigenous history curriculum where teachers and other stakeholders must be not only prepared to teach but conceptually invested in what they are teaching.

Indigenous YA literature can play two very important roles within and adjacent to tribal sovereignty and Indigenous history curricula. First, it can be the bridge that connects both the educator and the student to the content through emotional engagement and the nourishment of empathic engagement, helping to build the conceptual investment. But it can also fill in specific informational gaps for the reader. For instance, Washington’s Since Time Immemorial curriculum is focused on tribal nations in Washington State and the greater Pacific Northwest region. However, in order to more fully understand some of the larger concepts in STI, such as treaty rights, sovereignty, Native nations and the law, and government to government relationships, that are specific to the Pacific Northwest region, students need a broader understanding of Indigenous history, culture, and community across all of what we know as the United States and Canada.

This mystery follows Daunis Firekeeper as she navigates her mixed Anishinaabe and French heritage while becoming a confidential informant for the FBI as they investigate murder and meth in the Sault St. Marie/Sugar Island area of Michigan. This book was an instant New York Times bestseller, which not only shows us that this pageturner is popular with readers of many ages, but that the publishers decided to give it the marketing resources necessary to be a success right out of the gate. What moves readers through the book is descriptive writing that makes it easy to visualize the story, complex characters that many readers will easily identify with, and the desire to know who is responsible for the murders, who is creating and distributing the meth. But readers come away from this text with a much greater understanding of and context for jurisdictional issues within tribal, state, and federal law which is at the heart of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis. Readers begin to see the immense importance of the way Indigenous cultural teachings, such as the Anishinaabe Seven Grandfather Teachings, can be infused into the lives of contemporary Indigenous youth and adults.

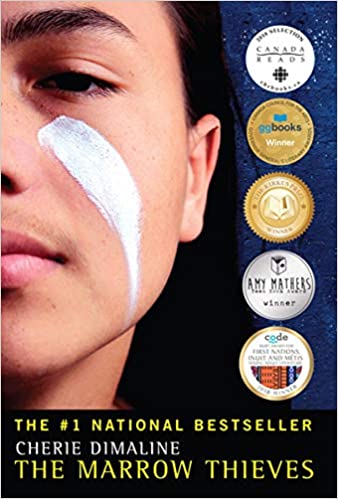

Indigenous YA literature, like these two excellent titles, can be an incredible support for teacher education programs preparing students to engage with tribal history curricula, even for those teachers planning on teaching in the elementary grades. For those planning on teaching in the secondary grades, reading these YA novels is also a preparation for the literary resources they might bring to their own classrooms. As Frenchie narrates in The Marrow Thieves, “We needed to remember Story….because it was imperative that we know…it was the only way to make the kinds of changes that were necessary to really survive” (25).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed