This week the guest contributor is Virginia Brackett. I, for one, appreciate her insight on how an understanding of a hero's journey can help us make connections to YA literature and the adolescents that read it. As we start our own journey into the new year, she offers us insight into this compelling instructional and analytical lens. Take it away Virginia

In class, we next search for monomyth elements in Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior: Memoir of a Girlhood Among Ghosts. Kingston focuses on story-telling to help her negotiate conflict with her mother and the development of her sense of self. As a narrator challenged by her Chinese- American heritage, Kingston includes Chinese myths that incorporate familiar archetypes and symbols. Through application of Campbell’s and Jung’s concepts to literature, students recognize their own susceptibility to American myths as children. Our discussion includes Disney’s influence on gender role development and its recent offering of stronger female characters, including Fa Mulan, the woman warrior of Kingston’s memoir. By the end of the course, many students joke that Campbell has ruined any chance that they may ever again enjoy a naïve viewing or reading of a quest story.

Learning theories like those of Alleen Pace Nilsen and Kenneth L. Donelson support Frye’s approach. Nilsen and Donelson proposed seven stages of categorization by children, including stage 3, “literary appreciation.” Additional theories, including that of Elizabeth M. Baeten, hold myth integral to cultural production and culture crucial to young readers’ self-realization. A study of children seven to 14 years showed them six familiar archetypes and associated them with objects from popular culture (a Power Ranger figure as a “hero,” for instance). Participants could then select reading material based on their preferred archetypes. Pointing out plot elements to eager readers promotes reading pleasure, offering them a key to decode literature that falls into the monomyth category. That key is context, and with such context, readers identify relationships between stories that may on the surface appear to be unrelated. For instance, young readers see that their favorite historical fiction hero is strongly related via the quest family tree to a science fiction hero.

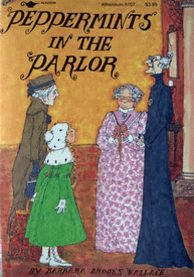

One day I was shocked and delighted to receive a phone call from Wallace herself. She said that she had read with appreciation my application of the monomyth and various learning theories to her novel, the first such analysis published about her book. She also confessed that she was surprised as I discussed her inclusion of the many monomyth elements that the article – their inclusion was unintentional on her part. That wonderful revelation illustrates the fact that much of our use of the monomyth is inspired via the osmosis that writers, who are avid reader, experience from an early age.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed