The first thing I heard Monday morning as the alarm went off was: “50 dead in Las Vegas Shooting.” I asked my wife, “Did you hear that?” I grabbed my phone and realized I had a host of text messages, missed calls and my Facebook notification number was unusually high. I was touched by how many people reached out. Thank you.

I am a Las Vegas native. Moving back to work at UNLV has been a joy. I have been able to reconnect with some people and hope to do more of that as time goes on. We are closer to family and that has been rewarding.

This tragedy has been difficult. It will continue to be difficult for many people here in Las Vegas, but in many other communities as families and friends deal with loss and recovery. I can’t begin to count the number of times I tear up as I hear a story about the event. I am proud of the work of all first responders, event staff, hotel staff, people who stood in line to give people, those who offered clothes food, and the people at the event who immediately became neighbors in the truest sense of the word. People who, without question, began to carry one another’s burdens.

I have listened to my students, who as young teachers or preservice teachers, explain how they have help their students, their friends, and their families. I am proud of them and of all teachers who respond to the emotional needs of people around them. Not only with this event, but with the waves of sadness and despair that accompany many of their students at different times and as a result of different events.

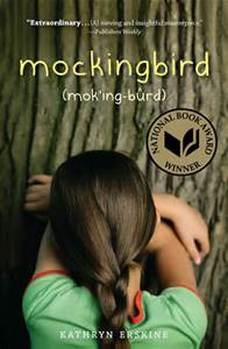

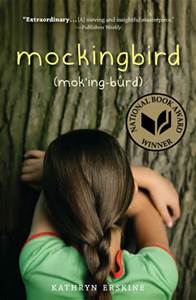

One of the helpers I have found even before today is Kathryn Erskine. In all fairness, I have been planning on talking about her work today for several months. She has a new book coming out next week, but we will get to that in a minute. I was going to rave about how much I like her work. I love Mockingbird. I know our class discussion of this work on Oct. 17, 2017 will now be radically different for a group of preservice teachers reading YA literature just two weeks after this tragic shooting.

| On the day that the National Book Award announces their short list, it is fitting that I like Kathryn, one of the past winners of the National Book Award speak. On Tuesday she posted on Facebook about messages she received from students in Las Vegas on Monday as they wrote to her about reading their class reading Mockingbird. "I wanted to talk about something that happened last night." Thus began a series of emails from children in Las Vegas who are reading my book, Mockingbird (which takes place after a school shooting). They are scared. They are confused. They are hurt. Why do we do this to our children? Here are more: "No one in my family got hurt that I know of." "What should we expect from this shooting?" "With more than 50 killed and 400 injured I am disturbed." "Me and my classmates are very sad and very scared. I am hoping that your book will comfort me." And the most gut-wrenching because it shows how these shootings make our kids feel powerless and unimportant: "Thank you for your time from a middle school student that does not matter that much in this world." So, go ahead, ask me if the lives of my children--and your children--are more important to me than the ability to carry a gun, because the answer is yes, and I wonder why you don't feel the same way. And don't bother responding with the bogus "2nd amendment right" or "my gun will save people" arguments. I am sick of it. |

He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed - love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

In her speech, Wolff calls them Faulkner’s six:

Like most authors, I have wondered since September 11th what I would ever write again, if I would ever write anything, and if so, would it matter? Usually, the answer has been no, for two months, the answer has been no. You understand, don't you? Of course.

Today my son, Anthony, and I went to the World Trade Center site and we walked around. What I saw was living proof of Faulkner's six. Faulkner said in 1949 in the Nobel speech that if we are not writing about these six things we are not doing our job. They are love, honor, pity, pride, compassion and sacrifice. I think of them as Faulkner's six. I used to have them on my wall until I memorized them…

We Make It Look Easy… by Kathryn Erskine

…at least, we try. As authors, we don’t want you to know how many thousands of hours it took to write and rewrite a book or how many walks we had to take to clear our heads or how much of the research isn’t in the actual story but serves to inform us (about 95%).

We simply want you to be sucked into the story, enjoying a smooth ride from start to finish. There should be no bumps – no thinking to yourself, “there’s no Cracker Barrel off that interstate in Michigan,” “no 14 year old talks like that,” “Empire didn’t premiere until 2015;” in short, we have to get the facts right. If you find even one error, we’ve lost our credibility. You’ll be looking for more potential errors, which takes your attention away from the story. We want you happily lost in our world.

I thought a lot about this boy, walking the rooms and grounds of Monticello, imagining being in his shoes. When I think about him, when I think about his mother … what would it have been like if my own son had been ripped away from me when he was eleven and I had to watch him from afar, not be able to hear his ideas, see him grow, feel his hug? I can only imagine – and that’s the point, I can only imagine. We don’t know what it was like to be an 11 year old boy who felt he had a rather normal, ordinary life like the rest of us and suddenly experiences the true horror of being enslaved, or what it was like for his mother and father, other family members, or anyone else involved. Fortunately, most of us have never experienced slavery. My job as an author is to try to experience the emotion myself and then put it into words so others can feel it, and in turn feel connected to the characters and, ideally, transfer that understanding to the historical and present day human experience and wonder how we could’ve gotten that way and how we can change.

Obviously, then, we need to give you more than facts and emotion. We need to write a story that engages you, keeps you reading, and maybe guessing, maybe even angsting. And if it’s going to teach you something, you shouldn’t even realize you’re learning about Quakers (Quaking) or autism (Mockingbird) or international adoption (The Absolute Value of Mike) or Civil Rights (Seeing Red) or Medieval England (The Badger Knight) or anxiety, not to mention a fair amount of science (The Incredible Magic of Being). Ideally, a story will make you think, but that should be painless, too; in fact, we want you spurred to anger or commitment, seeing the similarities to real life, freely researching more on the topic and sharing it with others. That’s when we know our hard work is done, that we’ve made the difficult look easy.

Someone invariably asks. I answer honestly, sometimes to gasps.

Where do you get your ideas?

Anywhere, everywhere—in the shower, on a walk, driving past someone who walks hunched over – what’s his story? Is he hurt? Is it physical or emotion? Is it temporary or permanent? Where’s he going? How is he feeling? What makes this day different for him than any other?

Why do people die in your books?

Because people die in real life. Because we have to learn how to keep living even after death, or after any kind of loss.

Did this really happen to you?

Not this, exactly. Probably something like it, though, even if it was the death of a relationship, or feeling trapped, or feeling ignored, or feeling scared, or any of the myriad emotions that the people – characters – in my books experience.

How much money do you make?

About a dollar on hardbacks, maybe ten cents (or less) on paperbacks.

That’s all? Then why do you write?

While some may write for the thrill of it or the challenge or to quell demons, I think many of us who write for young people want to give hope, encouragement, and a refuge. I certainly took solace and looked for answers in books, still do, and I want to share that companionship with others.

We don’t always get it right. I certainly don’t. I cringe at every passage that I should’ve written better. In fact, except for short sections I’ll read aloud if asked, I can’t read my books once they’re published – my muscles would lock up from excessive cringing. But we do try. We try to make story look easy. We have to write because we really don’t have a choice. It’s more a question of who we are, not what we do. It’s how we reach out to other human beings, hoping to entertain, yes, but also join forces, spread passion, and connect with those around us, and those who are still to come because really, we’re all connected. Story is what connects us all in this crazy, wonderful, frightening, funny, miraculous human drama.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed