Be sure to return next week when we survey the new issue of Study & Scrutiny and introduce everyone to our inaugural editorial board. Now, on to Lisa's comments:

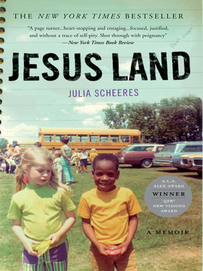

It was not until 2007 that I (finally and sadly) first discovered memoir. I stumbled upon Julia Scheeres’ Jesus Land in my local bookstore. Stacked on a table with several other titles, the cover transfixed me. I stopped, read the back cover, bought it, and devoured it in one sitting (Julia and her adopted brother, David, are on the cover). At the time I was teaching a young adult literature course at the University of Alabama and knew I wanted to include this Alex Award winner in my syllabus. For those unfamiliar with the Alex Award, it is given annually to ten books written for adults—published the year prior—that have special appeal to young adults, ages 12 through 18. Award-winning titles must be written in a genre that especially appeals to young adults, potentially appealing to teenagers, and well written and very readable (I will be posting about this award in April).

In the eight years that have passed since I first read Julia’s memoir, I have re-read it at least once per year, kept it (and “lost it” and bought more) in my lending library, written and presented on its relevance for high school students, and even had the privilege to spend an afternoon with the author herself in San Francisco.

In my contribution, I want to talk about why memoirs are important for readers and writers and why Jesus Land is particularly powerful. I will not be writing alone, as I have gathered insights from some colleagues around the country and Julia Scheeres herself.

The Walden Award Winner for 2015

The Walden Award Winner for 2015 As my co-authors and I wrote in 2008,

Milner and Milner (2003) claim that autobiographies— the genre of which memoirs belong—‘take us into the lives of others but at closer, more intimate range,” making us “eyewitnesses to actual events’ (252) and such works often catch adolescents’ natural interest about the lives of others. Memoirs differ from autobiographies in that “unlike autobiography, which moves in a dutiful line from birth to fame, omitting nothing significant, memoir assumes the life and ignores most of it. The writer of a memoir takes us back to a corner of his or her life that was unusually vivid or intense” (Zissner, 1987, 13, cited in Milner & Milner, 2003). In Jesus Land, Julia takes readers on a present-tense journey through her turbulent teenage years, a time that still profoundly affects her.

While some high schools assign memoirs as summer reading (titles such as The Glass Castle and A Long Way Gone come to mind), nothing much happens once school starts and the report/vocabulary/essay/quiz is completed. From my—albeit limited—experience with summer reading, there is little discussion of the text let alone any connecting it to what will be read or written in class that academic year.

I asked some of my fellow Walden Committee members to comment on why memoirs are an important genre to include in literacy classes. Mark Letcher shared, “While I appreciate the literary appeal of memoir, my biggest reason for exposing young readers to memoirs is that I want students to understand that everyone's story is important, and that their own stories are worth telling. I think memoir can be as much a gateway to effective writing instruction, as it can be to reading/literature instruction.” I could not agree more. My students come to school each day with a range of school and non-school related stories, and I find that the curriculum I have to teach, and the tests I have to give, does not often make room for their personal stories.

Joellen Maples agrees with Mark, adding “I have found them to be great exemplars of narrative writing which I find to be so important for beginning and even advanced writers . . . I love how they exemplify author's voice. The nature of storytelling in a way that traditional fiction texts may lack---plus it's a way for non-fiction to storytell.” I love the last part of her sentence: non-fiction to storytell. At a time when texts seem to be given the narrow descriptor of “informational” or “fiction,” there is a need to show students that genres do blend.

And then Lois Stover writes, “I like memoirs because they a) bring the past to life in the voice of a real person about whom I can come to care, and b) present various versions of the ‘truth’ about a point in time/incident/place and thus help me recognize the complexities of ‘truth’ as a concept, and help younger readers entering that Piagetian formal operational stage start to wrestle with the fact that there are shades of gray, not just blacks and whites.” Her definition describes perfectly the connection I had to Scheeres’ memoir—she was real, and because she was real I felt I could truly learn from what she wrote, more so than if she was a fictional character.

In Jesus Land, we are confronted with racism, underage drinking, and multiple forms of abuse—emotional, physical, and sexual—some of it from “Christians” in the name of religion. Jesus Land contains themes that would resonate with teen readers: a love story, survival, coming of age, betrayal, abuse of power, and family relationships, to name a few. Such themes are found in the traditional and contemporary works currently read, discussed, and analyzed in English class.

Referring back to the 2008 article written about Jesus Land, “As English teachers, we have relatively few problems deliberating about fictional religious and racial issues: Hester’s scarlet A, Atticus’ defense of Tom Robinson, or Jerry Renault’s refusal to sell chocolates. What will hook readers in Jesus Land, no matter how close to or far removed from Scheeres’ upbringing, is, ironically, their connection to issues of race and religion seen and experienced by Julia and David. Growing up in America, children and adolescents confront and are confronted by race and religion on a daily basis. In fact, the complexity of the two real-life issues sometimes renders students (and teachers) silent."

As you can tell, I am a fan of memoir, Jesus Land (you can read the first chapter here.), and Julia. Beyond her memoir, Julia has also published a fantastic book: A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown, which was named a Boston Globe and San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of 2011.

1. It's been a decade since Jesus Land was published. Could you comment on the response from readers on what the memoir has meant to them? Was there some feedback you didn't expect that has (pleasantly) surprised you? Have many teenagers contacted you? If so, what have they said?

I’ve gotten thousands of emails from readers, but I think my favorite response has been this one: “When I finished reading your book, I had an overwhelming urge to hug your brother.”

That’s deeply satisfying to me. When I set out to write “Jesus Land” I just wanted there to be record of David’s life. The grief I felt over his death and too brief time on earth was a burden too heavy to carry. Immortalizing him on the page --- his hopes, dreams, sorrow, humor despite everything – was a healing experience. But having readers respond so emotionally to his story, to email me in tears or saying that they felt like they “knew” my brother – that was rewarding to me. I felt like I had done him justice.

Teenagers do write me – they tend to identify with the story in some way. Either because they themselves feel like misfits or because of some element of the themes of religion/ racism/ sibling love/ parental neglect.

As far as pleasant surprises – I learned a few anecdotes about David that I hadn’t known before he died. One reader told me, and I was able to confirm, that he had a girlfriend before he died. The relationship was brief, and ended because her parents didn’t want her dating a black man, but I’m glad he was able to know physical love before he died.

2. Every adolescent that I have given the book to has been deeply impacted by it. I think what happens in the book, especially the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, is experienced by many teenagers. The book resonates with them. What would you say to teachers and/or administrators who might be hesitant to have the memoir in schools (say, due to language or sexual content)?

This response from adults always makes me snort – and not from amusement, but from disbelief. Puh-lease. What, teens don’t cuss? They don’t have sex? (I know parents want to delude themselves into thinking “not my child!” but really, experimentation is a normal, healthy part of human development). And teens will drink, have sex and sometimes use “bad words” whether their parents approve or not. It’s better to be real than delusional, in my view. Either way, my book does not glamorize sex. In fact, I’d argue the opposite – the sexual interludes are negative and predatory. “Jesus Land” may be a way to help kids to talk about their own negative sexual experiences – incest, pressure from boyfriends, rape, etc.

3. In a 2010 New Yorker article Daniel Mendelssohn wrote, "But the truth we seek from novels is different from the truth we seek from memoirs. Novels, you might say, represent 'a truth' about life, whereas memoirs and nonfiction accounts represent 'the truth' about specific things that have happened." What do you think about his belief?

I’d disagree. I think all good memoirs explore universal themes. Memoir must illuminate a greater truth. The details are specific to the author, of course – the particulars of her family/ town/ life. But the casual reader should relate to the subject matter or else it’s just navel gazing. This is why identifying the theme of your memoir is important. Most memoirs are survival memoirs – “I went through this crazy, dramatic time and I’m here to tell the tale” – but we can all identify with the despair and hope the author feels.

4. More recently, in a 2013 NY Times Opinion column ("How memoirists mold the truth"), Andre Aciman wrote, "Writing the past is never a neutral act. Writing always asks the past to justify itself, to give its reasons… provided we can live with the reasons. What we want is a narrative, not a log; a tale, not a trial. This is why most people write memoirs using the conventions not of history, but of fiction. It’s their revenge against facts that won’t go away." What are your thoughts on this?

Memoir walks a fine line between fiction and nonfiction. This is where the weird wiggle phrase “emotional truth” comes into play. Memoir isn’t journalism. There’s no way you can remember, verbatim, a conversation you had 25 years ago – much less one you had yesterday. What matters to us most about events from our past is their emotional impact – their meaning. That’s what memoir seeks to explore. Ergo, recreating scenes and dialogue is perfectly acceptable, provided they have a basis in truth. Because the memoirist must entertain the reader as well as enlighten her.

5. You lead writing workshops around the country to help writers reach their creative potential. What advice would you give to English teachers who want to have their students try memoir writing?

The building blocks of narrative nonfiction are scene, summary and musing. I’d ask them to focus on an event that had deep impact on them and walk them through each of these. First summarize the events/ problems leading up to the event to provide context/ background. Then slow time down and write a detailed scene (with dialogue, if possible) describing what happened. Then have them muse on the effect of the event (both internally and externally).

Hmm…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed