MEMOIRS for Reading and Writing by Lesley Roessing

As we hunker down in our homes, surrounded by family, we can transform time with relatives into memoir research as our students look through family albums and communicate with relatives and friends. And writers can practice another type of research, experiential research, as they reflect on their personal experiences. As writers learn about themselves while “researching” and writing their memoirs, memoir writing becomes inquiry—and memoir writing becomes a journey of self-discovery.

| What does memoir writing have to do with reading and MG/YA literature? As I discuss in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), reading memoirs provides mentor texts for writing memoirs. As readers read about people, places, objects, and events which are meaningful to published memoirists, they can notice and note how the memoirists write about these topics, using memoirs are mentors for their writings. In Bridging the Gap, teacher models, student examples, and reproducible charts are provided for this work. As an added bonus to meeting multiple state standards, memoirs bridge the gap between fiction and informative texts and compels the application of diverse reading strategies. |

Below are memoirs which I have recently read and reviewed and also memoirs read by my own middle grade students and in secondary classrooms where I have facilitated memoir units which include memoir reading.

Memoirs

When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, writer, I think of well-told important stories—whether contemporary or historical, memorable characters, critical messages. When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, person, I think of hugs, compassion, empathy, attention, and action. Now when I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, poet, I will ruminate on the power of words, the rhythm of words, the lyricism of words.

In this free verse memoir Anderson generously shares her life—the bottomless depths and the highest peaks—all that made her the force she is today. A challenging family life and the rape that “splits open your core with shrapnel,” clouds of doubt and self-loathing…anxiety, depression, and shame,” leaving “untreated pain / a cancer of the soul / that can kill you.” (69)

But also there were teachers, librarians, and the tutor who taught “the ants swarming across the pages” to form words and meaning, the lessons learned from Greek mythology, the gym teacher who cared enough to inspire her to shape-shift from “a lost stoner dirtbag / to a jock who hung out with exchange students, / wrote poetry for the literary magazine / and had a small group of …friends to sit with at lunch.” (88) and her home in Denmark which “taught me how to speak / again, how to reinterpret darkness and light, / strength and softness…redefine my true north / and start over.” (114)

She describes how the story of her first novel Speak found her and shares the origin of Melinda, “alone / with her fear / heart open, / unsheltered” (162)

Part Two bears witness to the stories of others, female and male, children, teens, and adults, connected through trauma and Melinda’s story, the questions of boys, confused, having never learned “the rules of intimacy or the law” (181) and the censorship, “the child of fear/ the father of ignorance” which keeps these stories away from them. Anderson raises the call to “sisters of the march” who never got the help they needed and deserved to “stand with us now / let’s be enraged aunties together.” (230)

And in Part Three the story returns to her American birth family, her father talking and “unrolling our family legacies of trauma and / silence.”

Shout is a tale of Truth: the truths that happened, the truths that we tell ourselves, the truths that we tell others, the truths that we live with; Shout is the power of Story—stories to tell and stories to be heard.

| Engle, Margarita. Enchanted Air: Two Cultures, Two Wings: A Memoir. Through this memoir in verse, the narrative of Engle’s childhood as a Cuban-American growing up in LA during the 1950-60’s, readers can experience the challenge of children torn between cultures and, and learn about the Cold War. When the revolution broke out in Cuba, Engle’s family fears for their far-away family in Cuba, a family they can no longer visit. Then, the Bay of Pigs Invasion creates hostile US/Cuba relations. I learned more about Cuban history, the Cuban Missile Crisis. and Cuban-American relations from this memoir than from my history courses as I lived through the times with young Margarita. |

I eagerly read Engle’s second memoir, a continuation of Enchanted Air which covers the years 1966-1973. For me, this was more reminiscing, than learning, about the lifestyle and events. As a reader of about the same age of young adult Margarita and possibly geographically crossing paths at some point, I am quite familiar with that time period.

Engle depicts a feeling of duality as she longs for Cuba, home of her “invisible twin,” now that travel is forbidden for North Americans.

Readers witness firsthand the era of hippies, an unpopular war, draft notices, drugs, and Martin Luther King’s speeches and assassination, riots, Cambodia, picket lines, as they follow 17-year-old bell-bottomed Margarita from her senior year of high school to her first university experience, fascinating college courses, books, unfortunate choices of boyfriends, dropping out, travel, homelessness, homecoming, college, agricultural studies, and finally, love.

At one point young Margarita as a member of a harsh creative writing critique group says, “If I ever scribble again, I’ll keep every treasured word secret.” (31). Thank goodness she didn’t. This beautifully written verse novel shares her story—and a bit of history—through poetry in many formats, including tanka, haiku, concrete, and the power of words.

| Ogle, Rex. Free Lunch. On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry. As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in full view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor. |

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in households which earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them; Free Lunch is his personal story.

Free Lunch, and other novels and memoirs about children affected by poverty, are necessary additions to classroom and school libraries so that readers can see their lives and the lives of their peers reflected and valued through story.

Growing up through the Fifties, Marilyn Nelson tells her story through fifty sonnet-style free-verse poems. Each poem has a location and year as readers follow Marilyn through her childhood on her quest to become the poet she is today.

| Ms. Nelson’s father was one of the first African American career officers in the United States Air Force, and as a military child, Marilyn moved frequently, literally crossing the country, from Ohio to Texas to Kansas to California to Oklahoma to Maine, experiencing the country, sometimes the only black student in an “all-except-for-me white class.” Readers can identify with the universal childhood experiences she shares, but there are also incidents driven by race and the time period providing history that we can learn from this memoir. This is a memoir of beginnings and endings and the search for identity and changing expectations—our own and that of others—in a confusing, sometimes hostile, world. It is about language and cloud-gathering and discovering poetry and the power of words. |

Front Desk’s ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Literature” list as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

| Thrash, Maggie. Honor Girl: A Graphic Memoir. Candlewick Press, 2015. Honor Girl is, as the title states, a graphic memoir, a format which is gaining popularity. Honor Girl is about a summer of discovery and identity. Maggie spent every summer at Camp Bellflower for girls. A typical Southern adolescent, she is a fan of the Backstreet Boys and awaiting her first kiss. However, this summer, the summer she is fifteen, she unexpectedly falls in love with a female counselor, surprising herself and questioning her sexuality as she experiences new, complex emotions. This is an honest coming out story, and the simple art style of this memoir supports and adds to the story. |

| Sones, Sonya. Stop Pretending: What Happened When My Big Sister Went Crazy. HarperTeen, 1999. I first met Sonya Sones when she talked about how she came to write about the topic of this memoir, her sister’s mental illness, in verse and heard her read some of the poems, Through free verse, the author captures the highs and lows of her thirteenth year, from “My Sister’s Christmas Eve Breakdown” to her fantasy of coming “To the Rescue” to the heartbreak of her “February 15th” birthday spent in the hospital visiting her sister to the joy of spending “Memorial Day” alone with Father to finally playing scrabble “In the Visiting Room” after her sister’ situation and her family’s adaption to it had become somewhat “BETTER.” When I read selected poems aloud to my students, I wished they could see the line breaks—I frequently refer to Sones as the Master of Line Breaks—and reading aloud, I would pause a microsecond shorter than a comma, so my students could feel the poetry. |

Ten student memoir favorites, some newer, some older:

Memoir Collections

On the first anniversary of the shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, I read the writings of the survivors of that unspeakable event. In this “yearbook,” students and teachers share their stories of grief, terror, anger, and hope, and honor those who died through narratives, letters, speeches, free verse and rhyming poetry, and art. As the editor, MSD English and journalism teacher Sarah Lerner, writes, “Watching my students find their voices after someone tried to silence them was impressive…. It was awe-inspiring. It was brave…. They turned their grief into words, into pictures, into something that helped them begin the healing process.”

“[The news] keeps coming in,

It doesn’t pause

Or give you a break. It keeps hitting you

With debilitating blows, one after the other,

As those missing responses remain empty,

And your messages remain unread.” –C. Chalita

“We entered a war zone.…I came out of that building a different person than the one who left for school that day.” –J. DeArce

“Somehow, through the darkness, we found another shade of love, too

something that outweighed the hate and swept the grays away.

A love so strong it transcended colors, something so empowering and true it couldn’t be traced to one hue.” – H. Korr

“I just don’t want to let go of all the people I love,

I want to continuously tell them “I love you” until

My voice is raw and my throat is sore” – S. Bonnin

“I invite you [Dear Mr. President] to learn, to hear the story from inside,

Cause if not now, when will be the right time to discuss?” –A. Sheehy

A look into the minds and hearts of those who experienced an event no one, especially adolescents, should ever expect to encounter as they share with readers in similar and disparate circumstances across the globe.

| Ehrlich, Amy, ed. When I Was Your Age, Volumes I & II: Original Stories about Growing Up. Candlewick, 2012. A collection of short funny, poignant, exciting memoirs by twenty well-known MG/YA authors, including Avi, Francesca Lia Block, Joseph Bruchac, Susan Cooper, Paul Fleischman, Karen Hesse, James Howe, E. L. Konigsburg, Reeve LIndbergh, Norma Fox Mazer, Nicholasa Mohr, Kyoko Mori, Walter Dean Myers, Howard Norman, Mary Pope Osborne, Katherine Paterson, Michael J. Rosen, Rita Williams-Garcia, Laurence Yep, and Jane Yolen. The authors also explain why they chose a particular memory as the basis for their memoir. Stories focus on events, people, places, or objects, and, in that way, lend themselves to serving as mentor texts for different types of memoir writing. |

| Gurtler, Janet, ed. You Too?: 25 Voices Share Their #MeToo Stories. Inkyard Press, 2020. Teens should realize that no young person—female or male—should be subject to sexual assault, or made to feel unsafe, less than, or degraded. Twenty-five YA authors share personal stories of physical and verbal abuse, harassment, and assault—from strangers, acquaintances, and family members. Included in this volume are stories of trial, loss, shame, and resilience and, most important, acknowledging self-worth. These essays illustrate to adolescent readers that there is no “right” way to deal with trauma; each survivor has to find their own way of processing and surviving trauma. This book will not only provide a mirror, sometimes unexpectedly, for some readers and a window for others, helping to build empathy, but will offer a map for many readers. This is a book that needs to be read and discussed by young women and men and the adults in their lives. Some familiar authors of diverse cultures who share their experiences are Eileen Hopkins, Cheryl Rainfield, Patty Blout, Ronni Davis, Nicholas DiDomizio, Andrea L. Rogers, and Lulabel Seitz. |

| Brock, Rose, ed. Hope Nation: YA Authors Share Personal Moments of Inspiration. Philomel Books. 2018. Contemporary adolescents are dealing with a variety of issues and feelings of powerlessness in a complex world that sometimes feels hopeless. Twenty-four YA authors speak to teens through poetry, essays, and letters of hope in this nonfiction collection. They inspire readers by sharing difficult childhoods and obstacles and experiences they overcame. Readers will appreciate the personal stories of authors of their favorite novels, such as David Levithan, Julie Murphy, Angie Thomas, Nic Stone, Libba Bray, Nicola Yoon, Jason Reynolds, and I.W.Gregorio. |

“Journalism itself is, as we know, history’s first draft.” (xiii)

With Their Eyes was written from not only a unique perspective—those who watched the attack on the World Trade Center and the fall of the towers from their vantage point at Stuyvesant High School, a mere four blocks from Ground Zero, but in a unique format. Inspired by the work of Anna Deavere Smith whose work combines interviews of subjects with performance to interpret their words, English teacher Annie Thomas led one student director, two student producers, and ten student cast members in the creation—the writing and performance—of this play.

The students interviewed members of the Stuyvesant High study body, faculty, administration, and staff and turned their stories of the historic day and the days that followed into poem-monologues. They transcribed and edited these interviews, keeping close to the interviewees’ words and speech patterns because “each individual has a particular story to tell and the story is more than words: the story is its rhythms and its breaths.” (xiv) They next rehearsed the monologues, each actor playing a variety of roles. Although cast members were chosen from all four grades and to represent the school’s diversity, actors did not necessarily match the culture of their interviewees. They next planned the order of the stories to speak to each other, “paint a picture of anger and panic, of hope and strength, of humor and resilience” (7), rehearsed, and presented two performances in February 2002.

With Their Eyes presents the stories of those affected by the events of 9/11 in diverse ways. It shares the stories of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors, special education students, an English teacher, a Social Studies teacher, the School Safety Agent, the Building Coordinator, a dining hall worker, a custodian, an assistant principal, and more, some male, some female, some named, others remain anonymous. Written as a play, readers are given a description of each character. Read and performed as a play, readers will experience the effect of Nine Eleven on others, actual people who lived that day and persisted in those days that followed, sharing their big moments and little thoughts. With Their Eyes was written with the thoughts and pens of a school community.

| Perkins, Mitali, ed. Open Mic: Riffs on Life Between Cultures in Ten Voices. 2013. Growing up "different" in the local culture is what the authors share in Open Mic—the stories, or “riffs on life,” of being culturally different. This is a book that should be in every MS/HS classroom, preferably a copy for every student to read, a collection that will generate important conversations about race and culture and fitting in, perhaps readers choosing a selection to read and discuss in small groups. Written in a variety of formats—graphic stories, free verse, and prose—and in first and third person perspectives, memoir and fiction (or maybe fictionalized versions of memoir) by ten different authors, many who will be recognized by adolescent readers, there are stories that will appeal to all readers and are necessary for many adolescents. Many are hilarious; editor Mitali Perkins explains that humor is “the best way to ease…conversations about race” (Introduction), and all are enlightening. Truly, this is a collection of stories that serve as mirrors, maps, and windows. |

| Mazer, Anne, ed. amzn.to/2VRrLxQGoing Where I’m Coming From: Memoirs of American Youth. 1995. These fourteen memoirs about immigration and bridging cultures, are set in Watts, Hawaii, New York, Boston, Cleveland, San Antonio, NJ, the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, the San Joaquin Valley, and rural Alabama. These stories of identity and self-discovery were written by such diverse authors as Luis Rodriguez, Ved Mehta, Thylias Moss, Naomi Shihab Nye, Lensey Namioka, and Gary Soto. |

Winchell, Mike. Been There, Done That: School Dazed. Grosset & Dunlap, 2016.

In these two unique memoir collections, popular authors show how and where they get stories. Each author shares a real-life experience and the original fictional short story that event inspired. Stories, relatable to readers everywhere, are divided into topics, such as dealing with peer pressure, putting others first, regret and guilt, change, morning school routines, class projects, and the dreaded school bus ride. Memoirists include well-known MG/YA authors Kate Messner, Julia Alvarez, Linda Sue Park, Lisa Yee, Alan Sitomer, Varian Johnson, Bruce Coville, and Meg Medina.

Biography-Memoirs

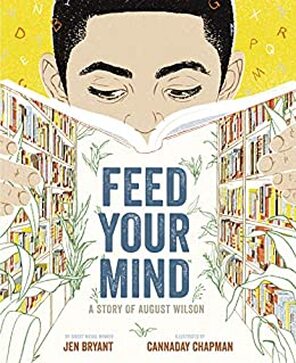

“If you can read, you can do anything—you can be anything.”—Daisy Wilson

Frederick August Kittle Jr., the son of a white German baker and Daisy Wilson, a black single mother who left school after sixth-grade, cleaned houses, and taught her four-year-old Freddy to read, overcame racism and poverty to become a Pulitzer prize-winning playwright.

Freddy left school when prejudice from classmates made it evident that he, the only black student, was not welcome in Central Catholic High and teachers at the public high school doubted his writing genius. Besides his mother, only Brother Dominic had faith in him, “You could be a writer.”

Freddy educated himself at the Carnegie Public Library though the works of such black writers as Hughes, Dunbar, Ellison, and Wright and the conversations of the Hill’s tribal elders—“warriors who survive in this hard world.” His job as a poet, and later as playwright, was “to keep [these voices] alive” though a collage of black characters from the Pittsburgh that never left him.

Through Jen Bryant’s verse biography, readers follow Freddy Kittle’s daily life as he grows into August Wilson, influenced by black writers and collage artist Romare Bearden and supported by fellow playwrights. Feed Your Mind, a picture book for readers of all ages, but particularly MG/HS, is hauntingly illustrated by Cannaday Chapman and includes a Timeline, Selected Bibliography, and list of Wilson’s plays.

All wars have two sides, but, as Winston Churchill said, “History is written by the victors.” Through history books and archives our students learn only one point of view, but we must disrupt the narrative with tales from the other side.

When our students study World War II—the war in Europe and the war with Japan, it is crucial that we help our students to see all perspectives and bear witness to the experiences of others. They need to learn that actions and decisions of governments have effects. One of those actions by the United States in 1945 was the bombing of Hiroshima, employing the first atomic bombs.

Through author Kathleen Burkinshaw’s poignant story, based on her mother’s childhood in Japan, readers can gain empathy and understanding for those innocent victims of war. This is the first-person narrative of 12-year-old Yuriko, her family members who are inundated with family secrets and shifting relationships, her neighbors who are sending their boys off to war, and her best friend. Through this important and well-written story, readers are introduced to Japanese culture, experience the strain of family secrets, and observe the war from the Japanese perspective. Not only a story of war, The Last Cherry Blossom is the story of family, heritage, and relationships.

This fascinating novel, or fictionalized memoir, of Malcolm X could have been titled “Before X” since it covers the time before Malcolm Little became Malcolm X or as written in the Author’s Note, “[it] represents the true journey of Malcolm Little, the adolescent, on the road to becoming Malcolm X.” (352)

Co-written by one of his daughters, Ilyasah Shabazz with one of my favorite writers, Kekla Magoon, X covers the years from 1931 to 1948 (the year Malcolm went to prison), focusing primarily on his teen years in Boston and New York City.

The reader experiences the significant influence of Malcolm’s father, a civil rights activist, and his mother who kept the family together after his father’s death, or murder, despite severe poverty until she was taken away to a mental institution and the children were divided among foster homes. The story also demonstrates the powerful influence of a high school teacher who, despite the fact that he was a top student and president of his class, told Malcolm that he could not aspire to be a lawyer and should aim for a profession as a carpenter. Taking that advice to heart, Malcolm drops out of school and renounces his father’s principles.

The timeline fluctuates from past to present which may be a little challenging for some readers; it might help to write in Malcolm’s ages next to the dates for readers. This novel is definitely for mature readers as teen Malcolm becomes involved in drugs and sex although there are no explicit depictions.

Through this well-written and an engaging text, the reader observes the changes Malcolm undergoes as he moves from a family life in Lansing, Michigan, to the influences of big-city life in the Roxbury and Harlem jazz neighborhoods of the 1940’s; from being Malcolm Little to signing first time he signed his name, on a letter to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Muslim leader, as Malcolm X. The extensive 6-page Author’s Note takes the reader through Malcolm’s transition, or “awakening,” during his prison experience.

Loving vs Virgina is the story behind the unanimous landmark decision of June 1967. Told in free verse through alternating narrations by Richard and Mildred, the story begins in Fall 1952 when 13-year old Mildred notices that her desk in the colored school is “ sad excuse for a desk” and her reader “reeks of grime and mildew and has been in the hands of many boys,” but she also relates the closeness of family and friends in her summer vacation essay. This closeness is also expressed in the family’s Saturday dinner where “folks drop by,” one of them being the boy who catches Mildred’s ball during the kickball game and “Because of him I don’t get home.” That boy is her neighbor, nineteen-year-old Richard Loving, and that phrase becomes truer than Mildred could have guessed.

On June 2, 1958, Richard, who is white, and Mildred marry in Washington, D.C., and on July 11, 1958 they are arrested at her parents’ house in Virginia. The couple spends the next ten years living in D.C., sneaking into Virginia, and finally contacting the American Civil Liberties Union who brings their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The documentary novel brings the story behind the case alive, interspersed with quotes, news headlines and news reports, maps, timelines, and information on the various court cases, and the players involved, as the case made its way to the Supreme Court.

Students can learn history from textbooks, from lectures, or more effectively and affectively, through the stories of the people involved. Novels are where readers learn empathy, vicariously living the lives of others.

Many of the same issues appear throughout history, wearing different masks; oppression, intolerance, and mistreatment of refugees have not ended, and we still need people unafraid to stand for their own rights and those of others. Audacity relates the true story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant with dreams of an education who sacrifices everything to fight for better working conditions for women in the factories of Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900's. Lyrically related in verse, the use of parallelism and the purposeful placement of the words is as effective as the words themselves.

The novel includes the history behind the story and a glossary of terms, a wonderful "text" for a social studies class. Readers not only learns the story of Clara Lemlich but experience the trials of the factory workers in NYC’s garment district and the obstacles Clara surmounted as she fought to organize the women to fight for their rights. Through the story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant who sacrifices her education to fight for the rights of factory workers on Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900’s, readers will learn about the struggles which led up to the Triangle Factory fire.

The story follows feminist Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda, known as Tula from 1827, from when she tells us that “Books are door-shaped portals…helping me feel less alone” to 1836 where she begins the first of her books to spread her hope of racial and gender equality.

As a girl, Tula reads in secret and burns her writings as reading and writing are unladylike. A13 she is nearing the age of forced marriage, and her grandfather and mother make plans to barter her for riches. The reader follows Tula through Engle’s beautiful verse as she writes plays and stories to give hope to orphaned children and slaves; refuses not one, but two arranged marriages; falls in love with a half-African freed slave who loves another; and at last independent, moves to Havana to be healed by poetry and plans the writing of “a gentle tale of love,” a story about how human souls are “free of all color, class, and gender,” an abolitionist novel written by the real Tula to spread her hope of racial and gender equality.

Picture Book Memoirs

Oral Memoirs

Seinfeld, Jerry. Halloween. Little, Brown and Company, 2002.

One oral memoir that works in classrooms of all ages is Jerry Seinfeld's "Halloween" (adapted into a picture book). Mr. Seinfeld shares Halloween experiences that are common to us all: the badly fitting costumes, being made to wear a coat over the costume (at least for us Northerners), trick or treating as a teen, and he ends with a reflection, the hallmark of memoir writing.

When working with adolescent writers, teachers can share a memoir from NPR's "Snap Judgment such as “The Garbage Man” about an adolescent’s first day at a new school.

One hilarious oral memoir I especially love and use with adolescents and adults is Carmen Agra Deedy's TED Talk "Spinning a Story of Mama".

Memoir Clubs

Memoir Clubs directions, strategies, and ideas for comparing/contrasting memoirs with other clubs or for club presentations to the class are described in Talking Texts: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

A Slide Show of all of the Memoirs

A middle school and high school teacher for twenty years, Lesley Roessing is the former Founding Director of the Coastal Savannah Writing Project at Georgia Southern University (formerly Armstrong State University) where she was also a Senior Lecturer in the College of Education. In 2018-19 she served as a Literacy Consultant with a K-8 school and now works independently, writing, providing professional development in literacy to schools, and visiting classrooms to facilitate reading and writing lessons. She can be contacted at [email protected] or through Facebook Messenger.

Lesley is the author of

- Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core;

- Comma Quest: The Rules They Followed. The Sentences They Saved;

- No More “Us” & “Them: Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect;

- The Write to Read: Response Journals That Increase Comprehension;

- Talking Texts: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum

- and has contributed chapters to Young Adult Literature in a Digital World: Textual Engagement though Visual Literacy; to Queer Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the English Language Arts Curriculum, and to the upcoming Story Frames.

Lesley served as past editor of Connections, the award-winning journal of the Georgia Council of Teachers of English. As a columnist for AMLE Magazine, she shared before, during, and after-reading response strategies across the curriculum through ten “Writing to Learn” columns.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed