|

Dr. Chea Parton is a farm girl and former rural student and high school English teacher. She’s currently an assistant professor of instruction at The University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation “Country-fied city or city-fied country?”: The impact of place on rural out-migrated literacy teachers’ identities and practices (2020) won honorable mention for the American Educational Research Association’s rural education special interest group’s dissertation award. Her research focuses on the lived experiences and identities of rural and out-migrant students and teachers as well as how they’re (in)visible in classrooms and YA literature. |

by Dr. Chea Parton

My sister and I have always joked that where we’re from is a geographical oddity (any O Brother Where Art Thou fans out there?) because it’s about 20 minutes from everywhere. In terms of the rural/remote spectrum, we’re definitely rural, having grown up on 80 acres with our closest neighbor a quarter mile away, but in terms of remoteness, we’re not that far from the nearest small city. On each of my trips into town, I found myself reliving other trips and the reasons for them. I could still name the families that used to live in the houses along the route I have always taken. The drive wasn’t only a physical and topographical journey – a journey in place, but it was also a mental journey through time and memories.

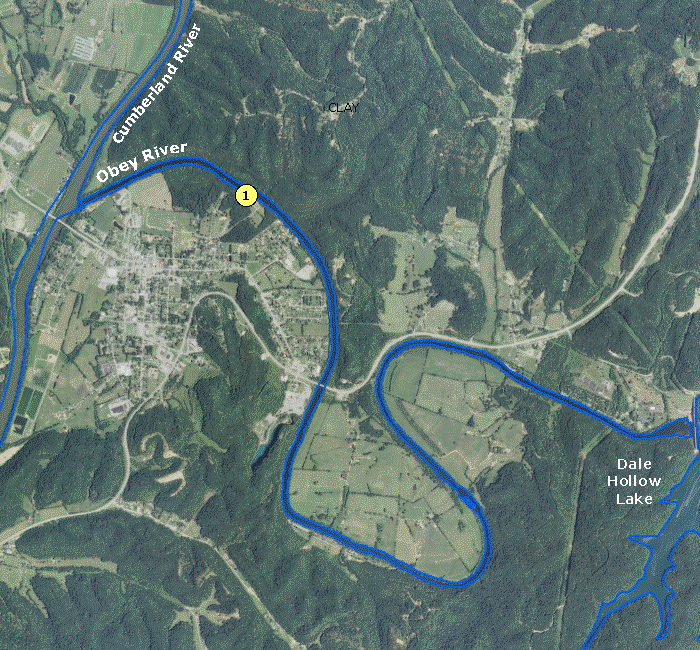

Reflecting on this later, I remembered how my Grandma Jean would often have difficulty talking about where she grew up in East Tennessee, but as soon as we got down there, the stories started flowing from her like the Obey River she played in as a kid. They were all rooted and connected to the physicality of the place she was from and where they were formed.

|

Place is More than Setting

All of this to say that place is more than just setting. But I don’t know that we think of rural places that way, especially in literature. Usually books about rural people and places are not known for their rurality; it’s just that the story happens to be set in a rural place. I mean, there’s an entire genre (problematic though it may be) dedicated to urban fiction. Why is there not a rural fiction counterpart? Why are rural stories not marketed and categorized in that way? How are teachers who are trying to find rural windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors (Bishop, 1990) for their students supposed to find them? |

As I discuss in a previous publication,

- Some of the teachers avoided contemporary rural YA in their own reading lives and classrooms because of the ways they have pushed back against and tried to escape the aspects of their rural upbringings and identities that they found untenable.

- Others simply had difficulty locating or thinking of titles of contemporary YAL even though they had a few older texts.

- In general, they didn’t have many rural books and hadn’t thought about teaching rural YAL as integral to (or even part of) culturally sustaining pedagogy, and frankly, neither had I.

My work and the Literacy in Place website is built on three major principles:

- Rural stories are worth reading and worthy of study.

- Rural stories are worth telling.

- Rural cultures are worth sustaining, even in their imperfection.

Because of the dominant deficit narratives and representations of rural people in popular culture and media (especially most recently around COVID and the election cycle) there are certain stereotypes that prove to be barriers in viewing rural experiences as worthy of reading/hearing/learning about. As a result, rural YAL with a critical lens is often missing from ELA curriculum (Petrone & Behrens, 2017; Parton & Godfrey, 2019) This is true across rural, suburban, and urban schools and classrooms. Even in my own rural education, I read very few titles that allowed me to see my rurality reflected in nuanced ways that rang true for me.

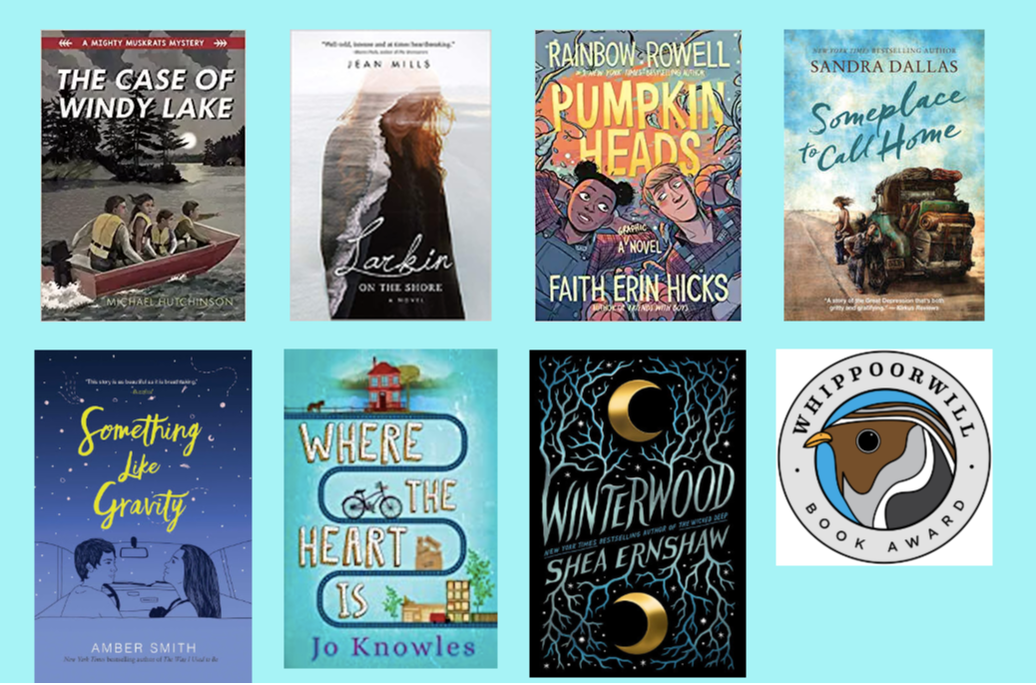

In order to help teachers learn more about and see that rural experiences are worth exploring in the classroom, I have created two main spaces where I analyze and discuss rural YAL: (1) my Reading Rural Goodreads account and (2) the Reading Rural YAL YouTube channel. In both of these spaces I detail aspects of rural YAL that spoke to me as a rural reader, the important perspectives they bring to critical thinking about people and their connections to places, and ways they could live in teachers’ classrooms.

These spaces are in their infancy and will continue to grow – hopefully with the help of good folks like yourself, dear reader.

If rural stories are important to read, then we need to be telling them. Growing up, I always associated published authors with major cities. I never believed that a little podunk hayseed like me could be the next Suzanne Collins or Veronica Roth or <insert other big name here>. And if I did become a writer, I never in a million years thought I’d be writing about rural experiences. Who would want to read that? Turns out – I would and I do. I didn’t realize how powerful seeing yourself reflected back at you from the pages of a book could be until it happened to me long after I left the rural classroom as student and teacher.

In order to emphasize that rural stories are worth telling, I started the (Non)Rural Voices blog. You may be asking why (Non)Rural. Well, because I wanted to be inclusive of rural out-migrant experiences. Scholars have written about and documented out-migration and rural brain-drain, but none of them have explored what happens to the leavers. Instead, they mostly consider what happens to the towns they left. It may be paradoxical, but it is possible to feel both rural and nonrural at the same time, and I want there to be space for those stories here. I envision (Non)Rural Voices to be a space where preservice and in-service teachers, teacher educators, and secondary students can have an authentic place to publish poetry, essays, short stories, etc. that capture their (non)rural experiences, further disrupting problematic notions of the rural as a monolith and illustrating the fact that rural stories are worth telling.

|

Rural Cultures Are Worth Sustaining Given the narratives surrounding rural people, I imagine that this statement might feel shocking. And this is mostly because popular culture has painted (and continues to paint) rural people as inherently conservative, racist, homophobic, inbred, toothless hillbillies and rednecks clinging to guns and Bibles. Like all stereotypes, this one isn’t necessarily completely wrong, it’s just incomplete. However, despite that, even in progressive scholarship, rurality is often reduced to these negative traits without nodding to any of the positive ones. For me, this is similar to the way that Paris and Alim (2014) point out that the misogyny in hip hop is problematic but doesn’t mean that urban cultures aren’t worth sustaining. |

It is my hope that Literacy in Place and the books, reviews, book talks, and blog posts detailing the lives, experiences, and cultures of (non)rural people can help us do just that.

I would love for all of these endeavors to be community-building and collaborative.

Want your students to read rural YAL and write Goodreads reviews? Let me know, and let’s publish them to the Reading Rural Goodreads account (giving them credit, of course).

Want your students to give book talks on rural YAL, reach out and let’s put them up on the Reading Rural YAL YouTube page.

Do you and/or your students have (non)rural stories to tell? Let’s work together to publish them as part of (Non)Rural Voices.

Would you like someone to come talk to your secondary or teacher ed class about rural YAL and/or teaching? I’d be happy to. Please reach out.

Have another idea you think would be helpful to teachers wanting to teach rural YAL, I’d love to hear it.

For all of these and any other inquiries, you can contact me here. For more updates about the goings on of the Literacy In Place website, follow me on Twitter: @readingrural.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed