See Kia's previous work for the blog here. Her blog post was entitled Language and Symptoms of Mental Illness in Young Adult Literature.

Both Kia and Diane have provided handouts and pdfs of their PowerPoint presentation during the summit (Find them on the summit page) They did excellent work and inspired many teachers. You will want to check out their work.

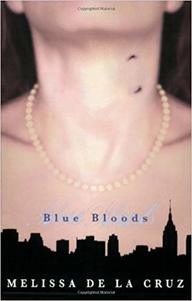

For now, however, I turn to Diane to give us an introduction to Melissa de la Cruz's YA works related to Hamilton.

Musical Theater Meets Historical Romance: Hamilton plus Alex and Eliza! by Diane Scrofano

We all noted that we wouldn’t be as dismissive or ashamed to admit we liked mysteries, for example, in the same way as romances. Sometimes sci-fi and fantasy genre fiction gets put-down, but that’s for geekiness, not girliness. I felt often on the defensive, reiterating to my students that we were doing scholarly study of this book, not just reading “hot trash,” as that same high-achieving student called it. “Yes, I know this is silly,” I seemed to say, “but we are looking at its cultural significance!” But then I would recollect myself, and I would challenge the students: Why should romance be deemed more trivial than any other part of life? Or family and personal life? (Perhaps it’s time to revisit “The Personal Is Political.”) One student objected to the main conflict in the novel, which was Eliza’s needing to be rescued from an unappealing arranged marriage, not only because it was historically untrue but also because “History is exciting…just imagine a line of six pound cannons firing or a cavalry charge cutting down fleeing infantry. Exciting and badass things were happening back then.” In other words, why focus on mushy love stuff when you could write about cannon fire? War and politics—those things, not love, are the stuff of interesting stories. I remember hastily scrawling in the margins, “Don’t you think your idea of what’s exciting is gendered?”

The novel Alex and Eliza, too, is problematic in its treatment of slavery. With Alex and Eliza set while she was still single and living in her parents’ house, there are mention of “servants,” but not of “slaves,” presumably to reflect the fact that Philip Schuyler called his slaves “servants,” according to the Schuyler Mansion Historical Society. However, what does this lead young readers to think? If they don’t know that Philip Schuyler (as did most other wealthy New Yorkers at the time) owned slaves, why wouldn’t they picture white servants? Especially troubling is the line, spoken by Eliza, declaring that “We Schuylers have always, always espoused a belief in the equality of black and white souls” (178). At this point in the novel, Alex is asking Eliza if she supports the abolition movement. I’m surprised that De La Cruz has Eliza respond not about herself merely but about the whole family and suggest that they have historically been abolitionist. The only reference I could find to the color of the “servants” in the whole book was in a sentence in which guests to Eliza’s Aunt Gertrude’s house “dump” their hats and coats “into the servant girl’s thin brown arms” (169). One might expect more of De La Cruz, a Filipina immigrant, herself a woman of color, but perhaps the issue is with the publisher, Putnam, sweeping the issue under the rug, as mainstream media has often done. In any case, Joanne Brown’s criteria for evaluating historical fiction can be brought up again: “Strict adherence to historical accuracy can pose a problem if ‘accuracy’ involves brutal or immoral behavior. What are the writer’s options when the intended readers are young adults, an audience for whom some readers may desire a subdued version of historical events?” A good question for students is who are the “some readers” who want a “subdued version” of history and why? Who does that “subdued” version protect? Who does that “subdued” version of history erase?

By the time the unit was over, my student who complained about the book cover did concede that this book was more than just a “cash grab” riding the coattails of the musical’s success. Since it brings up all these issues to discuss, I would agree. I’m eager to read Love and War.

Reference

Ball, Ankeet. “Ambition and Bondage: An Inquiry on Alexander Hamilton and Slavery.” Columbia University and Slavery. Columbia University. Retrieved from https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/ambition-bondage-inquiry-alexander-hamilton-and-slavery

Brown, Joanne. (1998). "Historical Fiction or Fictionalized History? Problems for Writers of Historical Novels for Young Adults." The ALAN Review, Vol. 26, No. 1. Retrieved from https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ALAN/fall98/brown.html

De La Cruz, Melissa. (2017). Alex and Eliza: A Love Story. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

——. (2018). Love and War: An Alex and Eliza Story. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Funiciello, Danielle. (5 Jun 2016). “An Overview of Slave Trade in New Netherland, New York and Schuyler Mansion.” Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site. Retrieved from http://schuylermansion.blogspot.com/2016/06/an-overview-of-slave-trade-in-new.html

Hanisch, Carol. (1970). “The Personal Is Political.” Retrieved from http://www.carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html

Kinkella, Susan and Diane Scrofano. (21 Mar. 2018). “Eliza: Historical and Literary Representations of Hamilton’s Better Half.” Moorpark College. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wS7K8ooUR_A&feature=share

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. (25 Sept. 2015). Hamilton: Original Broadway Cast Recording. Genius. Retrieved from https://genius.com/albums/Original-broadway-cast-of-hamilton/Hamilton-original-broadway-cast-recording

Onion, Rebecca. (5 Apr. 2016). “A Hamilton Skeptic on Why the Play Isn’t as Revolutionary As It Seems.” Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2016/04/a_hamilton_critic_on_why_the_musical_isn_t_so_revolutionary.html

Wolf, Stacy. (24 Feb. 2016). “Hamilton.” The Feminist Spectator. Princeton University. Retrieved from http://feministspectator.princeton.edu/2016/02/24/hamilton/

Until next week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed