Thanks Padma, for generously providing another post.

No Problem with "Problem" Books by Padma Venkatraman

| When my daughter was little, she declared with touching faith, "I told the kids in my class, my mommy never writes sad stuff about mean people." "Ummm..." I responded, as noncommittally as possible. "Even though I've never read any of your books," she continued, "I know you'd never, ever write about anyone getting hurt or having troubles, because you're the best mamma in the world." The truth is, of course, that without problems, we wouldn't have novels. Every novel in the world has, at its heart, a problem. Every novel is a "problem novel." Yet we've created a category of novels that we refer to as "girl problem novels." At the NCTE convention in 2018, authors Alison Myers, Kim Briggs, Katherine Locke and Abby Nash invited me to speak on a panel with them, entitled fierce females. This post, in fact, summarizes the suggestions I made that day on how we might celebrate female authors and female protagonists. |

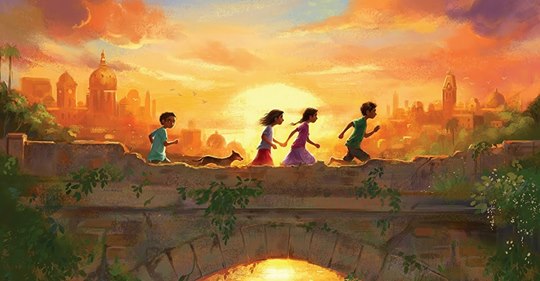

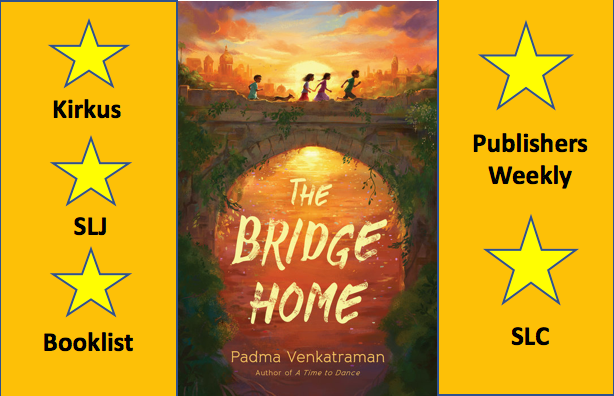

| A related issue: males are always considered the heroes of their stories; females are more often referred to as victims. When we speak of females as victims we do them a disservice, because we deny their heroism - they are heroes, too (or heroines if you prefer). The narrator of my fourth novel, THE BRIDGE HOME (released February 2019 by Nancy Paulsen Books), is a female who leaves home with her sister to escape domestic abuse. The siblings find themselves homeless on the streets of an Indian city, but there, they also find friends who become the family of their choosing. So, at face value, there are two social justice issues at the forefront of the novel: domestic abuse and poverty (hunger/homelessness). Both issues certainly impact females more severely than males; and it's important that we understand and acknowledge this. It's also important, however, that when we speak about such issues - whether in connection to a novel or not - we speak of the females who're subjected to such injustices as survivors and heroes, not victims. Rukku and Viji in THE BRIDGE HOME are survivors of a personal catastrophe, just as much as Brian Robeson is the surivor of a plane crash in Gary Paulsen's HATCHET. |

| Brian, by the way is often shown on the cover of the many versions of HATCHET in existence. His white male face doesn't decrease sales, because we, as adults, have no problem distributing books with males on the cover to female readers. Unfortunately, however, to this day, we do have trouble recommending books with females on the cover to male readers. I've heard too many librarians, teachers, and authors speak of "girl books" and "boy books." I'll never forget the day I walked into my local library (less than ten years ago, which doesn't seem that long to me) - and saw a list of "books for girls" and "books for boys." I was pained (but unfortunately not surprised) to see that this list, which breaks the world up into two gender categories, went on to list books about fossils, volcanoes, maps, etc. as books for boys, and listed books on cooking, knitting and princesses for girls (I'm not sure princesses knit - but that's a minor point). |

| I had a long conversation with the librarians and after that I must say I never came across a list like that at that library. But it was hard to convince them of my point - which was that they needed to actively promote books they enjoyed to everyone, regardless of gender. And that they needed to look at their patrons as human beings first, not consider their patrons' genders as a defining feature of reading interest. After all, isn't Malinda Lo's ASH a book for anyone who enjoys a richly imagined fantasy written in lyrial language, with well-defined characters? Does the gender of the author or the love interest of the protagonist limit who, as a reader, might love the book? I sincerely hope not - because this is a book (and an author) who deserves to be embraced by many readers, and who has, I am happy to note, found a wide following. Yes, I know the reality is that boys gravitate toward books featuring male protagonists, not books depicting females on the cover, for the most part. But I, for one, am not willing to accept the status quo. I never have been. As long as I am alive, I hope to fight for equality - and that includes fighting against gender divides in books. |

I'd like to end by encouraging us all (and I include myself because goodness knows I still have heaps to learn), to listen as much as we can to those who discuss such issues. Here, then are a two excellent sources to look at: ALA's Amelia Bloomer list - which features books with strong female protagonists; and Grace Lin's kidlit women podcast series. And if you do enjoy them enough to subscribe, I beg you not to just focus on new and upcoming titles or podcasts or lists or posts - but also to re-read archives. We may not always agree 100% with every opinion we hear or with every choice of a book on a list - and we don't need to. I firmly believe that practicing the art of listening is in itself something that broadens our minds and hearts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed