On a Sunbeam and the (extra)Ordinariness of Outer Space

| Dr. Fawn Canady is an Associate Professor of Adolescent and Digital Literacies at Sonoma State University in Northern California. Fawn co-directed the NEH Human/Nature Climate Futurisms Institute. She is a former high school English teacher who prepares literacy teachers K-12. Her interdisciplinary interests include multimodality, climate change literacies, community engagement around literacies, and teacher education. |

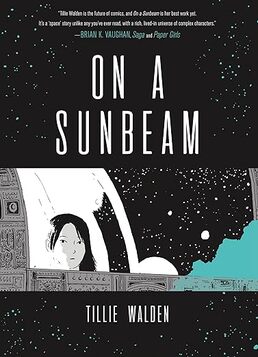

This post explores the graphic novel On a Sunbeam through themes that have surfaced in my work on dystopian climate fiction (cli-fi) as ironically hopeful. It is a story about two high school girls, Mia and Grace, who fall in love and are separated. The major plot line is Mia’s quest to find Grace. However, equal attention is paid to the supporting cast because it is also a story about a family that has been found. Mia ends up with a restoration crew that travels from planet to planet to restore ruins. The story begins in the present, with Mia as the new crew member, and follows her as she cultivates relationships with her new co-workers to the point that they become family. In the process, we are invited to reflect deeply on what it means to be a family. What sacrifices are we willing to make?

Flashbacks create a parallel story where we learn about Grace, Mia’s first and now lost love. The two stories careen toward an intersecting point in the present, where Mia decides to find Grace again. This is where the found family is tested and rises to the challenge. It’s a beautifully told and illustrated story about relationships.

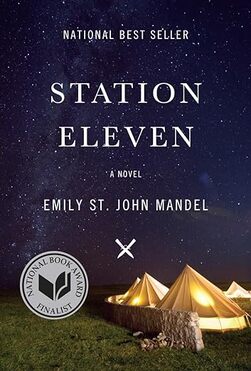

I picked up On a Sunbeam because of the comic in the series and the book Station Eleven. In Station Eleven, an acting troupe called The Traveling Symphony performs Shakespeare in a post-apocalyptic world decimated by a pandemic. This troupe is the family that the protagonist, Kirsten, has found. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the book within the book. A shadowy character, The Prophet, and the children who follow him take as their new bible a comic or graphic novel about a space colony: Station Eleven.

This comic inspired me to take up a thematic thread I’ve been following through dystopian YA under the umbrella of climate futurism or possible futures for life on our planet. It seems space is featured in many books I’ve read or figures large in the characters' imagination. Readers and teachers may find that starting over, choosing family, and ultimately “just” living are great starting points for exploring space in YA cli fi. These stories complement each other.

Following characters into outer space or learning about how space figures in their imagination has me thinking about how stories can connect us to home or help us make a new one. Stories can also help us build relationships to form and fortify our found family.

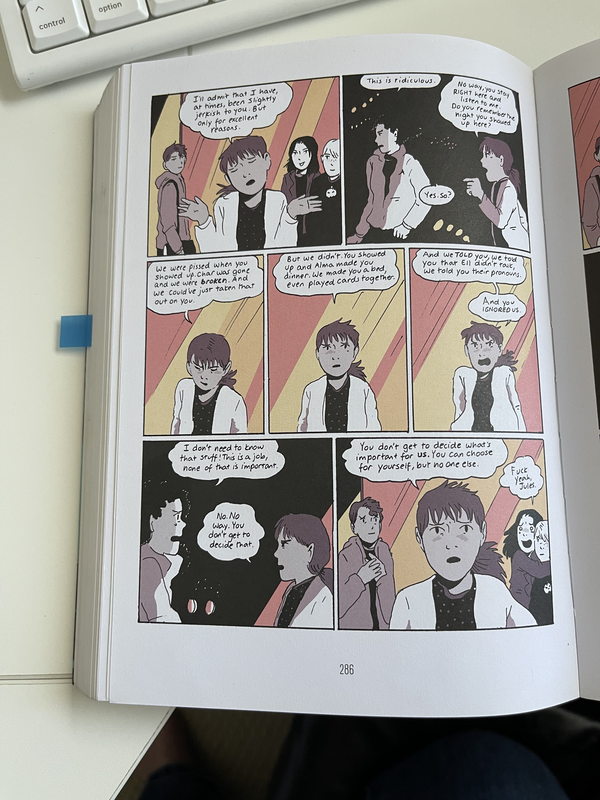

The found family trope can be defined simply as the family of choice. In a recent ALA blog, Estefanía Vélez notes:

Jo: I don’t need to know that stuff. This is a job. None of that is important.

Jules: No. No way. You don’t get to decide that. You don’t get to decide what’s important for us. You can choose for yourself, but no one else.

All: Fuck yeah, Jules.

In Station Eleven, old but persistent mindsets are from “The Before.” Survivors in many communities go to great lengths to resist ideas that no longer serve humanity. The tragedy of the pandemic is an opportunity to start over. Old ideas surface in On a Sunbeam that still threaten colonized planets in space in the same ways they threaten us now.

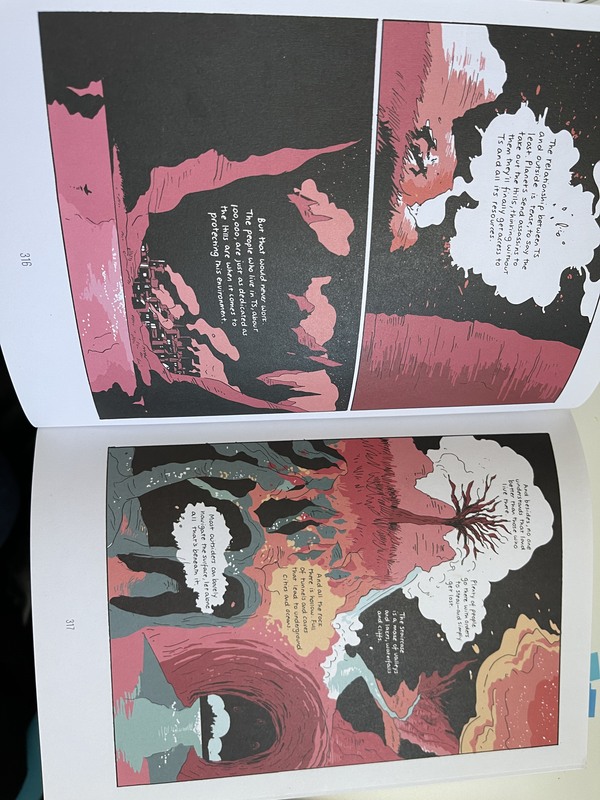

One current challenge in dystopian literature is a worldview that centers on an extraction mindset, or a belief that the natural world consists of resources to be extracted to generate goods or to be used up. In On a Sunbeam, colonizing space means that the old ideas that forced humans to look to the stars as a means of escape have followed them. The book includes many examples of conflicting views about protecting environments on other planets and extracting or exploiting their resources and more-than-human beings. The excerpt or panels from the book show an example of the conflicts between communities that protect and those that seek to exploit (Walden, 2018, pp. 316-317). There are also examples of creatures revered by cultures on distant planets. Reading Braiding Sweetgrass alongside On a Sunbeam surfaces subthemes like respect and reciprocity (see Image 2). It asks us to seek the right way to live in relationship with more-than-human beings. We can and must choose different stories: “The stories we choose shape our behaviors and have adaptive consequences” (Kimmerer).

I am reminded of Odum, one of the so-called forefathers of ecology who compared planet Earth to a self-sustaining spaceship- reminding us of the complex life systems we have yet to replicate successfully. In space, we are still very much dependent on the resources and support from our home planet. Surely, there have been advances, but he talked about Earth as life-support so complex that we can’t venture too far without it, like an umbilical cord. Space travel, colonizing other planets, is an extraordinary accomplishment. Yet, one of the big takeaways of On a Sunbeam is that “ordinary” human lives happen everywhere–even in space. Astrophysics reminds us that we are made of the same stuff as stars. In On a Sunbeam, the drama of space travel and planetary colonization is juxtaposed with “small” dramas like high school bullies, love and loss, dreams deferred, and resistance to school or work. In other words, our lives are both miraculous and banal at the same time, even in space.

Station Eleven compelled me to explore stories about space and would be an obvious pairing with On a Sunbeam. The story within the story of the distant space station will share some parallels with On a Sunbeam. Found family is a thread in all three. We need each other to survive.

For those who want to follow the dystopian thread, the books I’ve written about before are great starting points: The Parable of the Sower, The Marrow Thieves, and Feed would all bring out found family themes but also amplify others, such as extractivist mindset, the perils of capitalism, the importance of place, and the power of narrative inheritance (the former) and what happens when stories are gone (the latter).

If you want to re-story and focus on place, including new places in outer space, The Last Cuentista and Braiding Sweetgrass for Adolescents would help us consider how stories “have adaptive consequences” (Kimmerer). How do the characters in On a Sunbeam use stories? The children’s book Remember, based on Joy Harjo’s poem, reminds us that we are part of the universe and connected to everything. Other books help us connect to the imagination, such as See You in the Cosmos (Jack Cheng) and We Dream of Space (Erin Entrada Kelly, a middle-grade novel).

Interested in Space Travel? Neil deGrasse Tyson’s YA book Astrophysics for Young People in a Hurry, illustrated by Gregory Mone, would be a fun way to remind ourselves that we are part of the universe and that it is full of wonder and still beautifully ordinary at the same time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed