Reminiscent Reading: Reflecting Back on Books That I Just Don’t Forget

I am a proud father and grandfather. I loved spending time with all my children and grandchildren over the last several weeks. As an avid reader I connect many events—past and present—to reading experiences. My oldest son, Isaac, is working on a Ph.D in music education at Arizona State University. While we were visiting his office space and the building in which he both takes and teaches classes, I couldn’t escape the fact that I was once again visiting a campus that housed the first incarnation of The ALAN Review. Alleen Nilson and Ken Donelson began the journal as early career professors over forty years ago. The journal returned to ASU under the direction of Jim Blasingame and Lori Goodson, for another editorial cycle from Volume 31 through Volume 36. I just finished an editorial run with my co-editors Jackie Bach and Melanie Hundley, so I was understandably nostalgic. Conversations and the context of the conversations almost always reminds me of books.

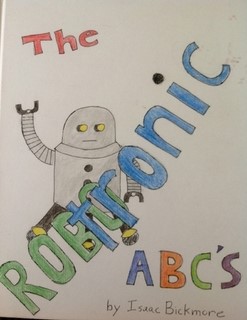

In the midst of doing graduate work, Isaac stays intimately connected to the literacy development of his two sons, Will, 5, and Van, 3. Both of his children are extremely bright and interested in reading, writing, and drawing (no grandparent bias here, of course). Isaac has nurtured this impulse by creating and self-publishing an alphabet book based on robots—one of Will’s seemingly endless obsessions. Everyone should buy one of course!

This post is not about shameless family self-promotion, okay, well maybe a bit. Mainly, it is about my literacy memory that occurred as Isaac shared his book and as we chatted about reading. I was reminded of a book from my own early adolescence that I think about from time to time--Andy Buckram’s Tin Men by Carol Ryrie Brink. This was a wonderful book. I read it a couple of times as a kid and as a teacher and, now, as an English educator that focuses on reading and young adult literature, it is a book I wish I owned.

Sara Kajder posted on Facebook about her challenges with participating in an independent reading program driven by Accelerated Reader. She describes a son, who, while a reluctant reader, is beginning to read more and more. He has found a series of books he likes, but reading those books generates no points from the AR program. So, as far as the program is concerned, he would not be “reading.” Come on! As an English Educator I know this is bunk, as a past editor of The ALAN Review it drives me wild, and as a parent it breaks my heart. I started wondering about Andy Buckram’s Tin Men and other books I read growing up. Would they pass the test to be qualified as AR books at any level?

I picked four books or book series--Andy Buckram’s Tin Men (Brink & Mars, 1966), Homer Price (McCloskey, 1943), the Herbert series —that I enjoyed in my late elementary years to see how they measure up or if we are losing track of classic children’s and adolescent (juvenile) books. To say that I enjoyed them is an understatement. These are the books, that as I read them, I would jump up, find my mother, and read her passages I thought were funny. It is her own fault that she had to endure these impromptu moments of sharing; she started it all with that bedtime story routine. Poor Andy and his wonderful Tin Men don’t make the AR list. It is out of print; hopefully, it is still hiding in public libraries. It was written by a Newbery winner, Carol Ryrie Brink. Are we destined to only keep track of the award winning titles?

Homer Price has a better outcome that Andy. Two books featuring Homer have AR ratings, both at the 6 grade level. This makes me uneasy. I like that they are acknowledged, but resist that they are labeled. I think curious, slightly mischievous boys would relish participating, even vicariously, with Homer in his adventures. Perhaps Homer fairs better than Andy because his author, Robert McCloskey, won two Caldecott Medals as opposed to Brink’s single Newbery Award. Even more troubling, we frequently hold on to older books written by males as opposed to females; dare I even open that can of worms?

The Herbert series doesn’t even get a mention in the AR BookFinder. This is disappointing. Hazel Hutchins Wilson wrote over 15 books for adolescent readers. Some of them are fiction and others are based on historical figures. She was a librarian throughout her life and her papers are collected at the University of Oregon. She made a notable contribution to children’s literature as a writer. In addition, she worked at secondary schools and universities as a librarian. I devoured these books. It bothers me at the thought that if a parent or a child found these wonderful books at a library, a bookstore, or a garage sale they just wouldn’t be adequate for the boundaries of an AR program.

Of all of the characters, Rupert Piper, Ethelyn M. Parkinson’s creation, fares the worst. Her books don’t have a single mention in the AR BookFinder. I loved these books. I thought they were funny, engaging, and creative. I still have a specific memory of reading to my mother from a Rupert book as she worked in the kitchen. I read and laughed as she carefully listened; I become a reader, a high school English teacher, an English educator, and a critic of young adult literature. My parents took me to the book mobile and the library and they didn’t care which books I checked out or whether or not I finished them. My teachers took me to the library as well; they suggested books, but mainly, they encouraged reading through modeling. Parkinson wrote quite a few adolescent novels. It is hard to find information about her or many of her books. The LSU library didn’t have any of her books. Some can be found on Amazon. I hope others discover the Rupert books and find them as quirky as I did. Granted, Rupert, Homer, Herbert, and Andy represent a different era in publishing. Nevertheless, the principle is the same. I became a reader because I was ushered in slowly. I was read to by my mother and by teachers. They nurtured my interest and suggested titles. I kept charts and wrote reports. I know that there were rewards along the way, at home and at school--I got to be one of the classroom librarians in our sixth grade in-class library. But I never had to read to a specific list or take a test on my self-selected reading, thank goodness. Some of my choices were too tough the first time around;—Moby Dick didn’t cut it when I was in the seventh grade, or the eleventh grade, but I inhaled it in college. Kylene Beers suggested in a recent Facebook post: “The right book isn't determined by a Lexile level (or an AR ranking). It's determined by your inability to stop reading it no matter what anyone says.” If we find a kid reading and then we find out that child is communicating with parents or guardians, we should make some suggestions, monitor progress, teach pre, post, and during reading skills, encourage conversation, and more importantly, get out of their way. Rather than discourage reading by limiting reading choices through tightly defined programs, we should be fostering true self-selected reading.

Until next week,

Steven T. Bickmore

RSS Feed

RSS Feed