Her posts are perfect as a Monday Motivator. Teachers can start their class by giving several book talks from Lesley's list or they can allow student to browse the blog post if their students have access to the internet on digital devices.

Once again, Lesley has over twenty different posts! All of them would be useful as a Monday Motivator that can be used on any day of the week. Make sure to browse the Contributor's page and bookmark several of Lesley's posts for easy access.

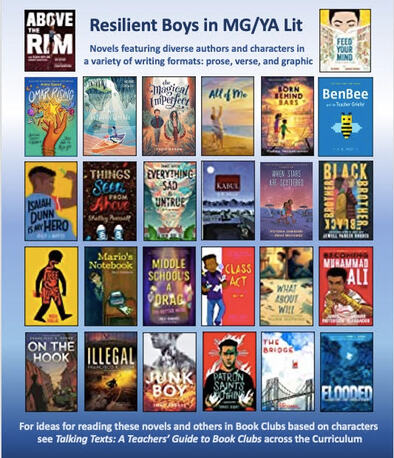

Resilient Boys in MG/YA Literature

Lesley Roessing

Life has always presented challenges to children and adolescents. I don’t know if the types of challenges have changed, if more children are affected by difficulties, or if we are more aware of the challenges our young people are facing, such as bullying, poverty, homelessness, immigration, mental illness, neurodiversity, physical differences, gender identification, loss, abuse, prejudice and discrimination, parent incarceration, parenthood, and even disease and natural disasters. However, medical groups have said the coronavirus pandemic has worsened a mental health crisis among children and teenagers (nytimes.com/2021/10/19). Sometimes strength and resilience are revealed through having the confidence to be ourselves and sometimes by having the courage to transform ourselves into the persons we know we could be.

As I have mentioned in many of my writings about literature, readers need to recognize themselves and see their lives reflected in books to realize that they are not alone and their problems are not unique. Readers can also see story and characters’ decisions as maps to help them navigate life. Just as important are books that cause readers to experience the lives of those they may see as ”others” in order to develop empathy and respect for their peers and to catch glimpses into the lives of children they may not personally encounter or those who are “hiding in plain sight.” The value of books, such as those listed and reviewed here, is to generate important conversations; adolescents are more willingly discuss characters and how characters handle, or mishandle, conflicts and personal issues than discuss themselves, their difficulties and concerns, and their actions and decisions. In this way, books can also serve as bibliotherapy.

As an update to my September 2019 guest-blog “25 Strong Boys in MG/YA Literature (Plus 5 Strong Girl-Boy Partnerships)”, I review 26 more novels/memoirs written by diverse authors, featuring resilient characters who collectively face a variety of challenges. These boys display strength of many kinds, sometimes with the assistance and support of others.

I also took the opportunity to ask some of the authors why or how they created and wrote about the male characters in their novels and why they wrote about the challenges that their male characters face.

• • •

Junk Boy introduces reads to two teen outliers, two dysfunctional families, two stories which become intertwined.

there is no putting

a tree back up after

it’s broken

and fallen

in a storm

maybe with us

with people

it’s different (336)

Bobby Lang, nicknamed Junk by the bullies at school because he lives in a place that has become a junkyard, spends his time flying under the radar, eyes down, not speaking. His father is drunk, abusive, unemployed, and listens to sad country songs; his mother left when he was a baby is, according to his father, is dead. Bobby has no self-confidence and little self-worth but then he meets Rachel, a talented artist who sees something else in him.

her eyes could

somehow see a me

that is more me

than I am

that is so weirdly more

so better than

actual

me (273-4)

But Rachel has her own family problems. Her father has just moved out and her physically-abusive mother wants the local priest to “reformat” Rachel who is gay.

As Rachel moves in and out of Bobby’s life, her need helps him figure out

what was I going to

say

do

be? (274)

And what he is, or becomes, is a rescuer and protector, a savior. As Father Percy tells him, “It’s what she found in you…” (352)

Reading Tony Abbott’s first verse novel, I felt like I was watching a movie unfold as I followed the protagonist on his hero’s journey.

| Tony Abbott: With Bobby Lang in Junk Boy, I fell back to when I was in high school and felt an outsider to so many of the groups that form there — and I took that to the extreme, writing Bobby as if I had let myself go deeper into myself to the point of invisibility and listening to what he says about it. It’s in a kind of free verse because this is the way he feels. It’s comforting in a way, to think about how you can move not with but beside the flow of popular life. It can be a full life, and Bobby loves nature and solitude and art. Still, a yearning heart beats in him — legacy of the pain his father (and by extension he himself) suffers, and he finds himself drawn into Rachel’s life, much against his solipsism. Over the last few years, I suppose I’ve tried to write characters that are struggling with, working through, the junk that life can heap upon an unready soul. This is the situation with Jeff in The Great Jeff and Owen in The Summer of Owen Todd; it’s probably also true of Denis in Denis Ever After. This is why I wanted my last four novels to bear the names of the people I try to celebrate. |

Traditionally, the United States has long been the global leader in resettling refugees, strictly defined as people forced to flee their home country to escape war, persecution or violence. (https://www.smithsonianmag.com) The number of refugee children has increased over the past decade. With approximately 350 refugee resettlement agencies spread throughout nearly all 50 states, refugee children can be found in classrooms throughout the country. Together with immigrants, these newcomer children make up one in five children in the U.S. (https://brycs.org)

Many children look around their classrooms and wonder, Who are these kids and why are they here? Some parrot opinions heard from the adults in their lives—both positive and negative.

Mario, a survivor of the Salvadoran Civil War of the 1980s, was one of those newcomers. Mario witnessed his father, a journalist, being taken away from their home. “All I can do is watch. Watch as the soldiers blindfold Papa. Watch as they shove him out the door. Watch as Mama collapses to the floor.” (21) He later learns of the death of his father, killed by the soldiers.

Mario with his mother and younger brother are smuggled to the United States where they are given an apartment, food, clothes, and toys, and Mario wonders, “Will anything in my life ever feel right?” (44) Mario is enrolled in fifth grade where all the children accept him, especially twins William and LaShaunda, except for the class bully Randall. When discussing an article on deportation in social studies class, Randall has no trouble sharing his opinions. “My father says people like this should go back to their own countries. We didn’t ask them to come here.” (83)

And after a small incident in his father’s store, Randall threatens Mario and his family. “My father could get you kicked out of the country, you know.” (79)

Mario struggles with feelings of betrayal by his father’s political articles, actions which led to their current situation. When he finally has the courage to read the notebook his father left him—and the article his father signaled him to pull from the typewriter the night he was taken—he reaches understanding of his father’s heroism and the importance of letting the world know of the war, persecution, and violence occurring in his country.

Mary Atkinson’s short novel is not only a good story with engaging, well-developed characters, can serve as an effective tool for generating important conversations about refugee admissions and resettlement and the importance of opening our hearts (and our borders).

• Fact: An estimated 1 out of 14 children in the U.S. will experience the death of a parent or sibling before they reach the age of 18; one out of every 20 children aged fifteen and younger will suffer the loss of one or both parents.

• Fact: The number of homeless students enrolled in public school districts and reported by state educational agencies during school year 2017-18 was 1,508,265. This number does not reflect the totality of children and youth experiencing homelessness, as it only includes those students who are enrolled in public school districts or local educational agencies.

• Fact: In many cases these two facts may be related.

• Statistically these children are hiding in plain sight in our classrooms. Some of them are our students and others are our students’ friends. Readers need to see their lives and the lives of their classmates reflected in story to feel heard and valued and to gain empathy for others.

Isaiah Dunn was one of these children. After his father died suddenly of a heart attack, his mother, too depressed to work, took her solace in bottles. “But I do think. About how the world can be good and happy for one person, but bad and sad for somebody else. And how everything can change in just one minute…like it did for me, Mama, Daddy, and Charlie.” (21) Fifth-grader Isaiah, his mother, and his 4-year-old sister Charlise lost their apartment and moved into the “Smokey Inn,” which is how Isaiah refers to their motel. But they then lost even that, living in their car until they were rescued by a former neighbor.

“Every day Mrs. Fisher writes a sentence on the board, and we have a few minutes to write something about it. Today she wrote, ‘My world is a good and happy place.” (21)…I keep my workbook closed, too, cuz there’s no way I’m writing and words about being safe and happy.” (23) And a few days later, “I wanna tell Mrs. Fisher there’s no way I’m writing about ‘my favorite room in my house’.”(55)

But Isaiah does have his father’s notebook of stories of the superhero Isaiah Dunn which he reads slowly and savors, and he has a love of words, a talent for writing poems, and the goal of making enough money somehow to move his family into a house. He truly wants to be Isaiah Dunn, Superhero. But life is tough, and young adolescent lives are complicated under the best of circumstances. The reader follows Isaiah’s year as he navigates changing relationships with classmates and faces his own grief, attempting to hold his family together, and we cheer him on as he creates a lasting tribute to his father’s memory.

Isaiah Dunn’s story began in the short story anthology Flying Lessons, and author Kelly Baptist develops this engaging character in this first novel which I devoured in one day and a small box of tissues.

Seventh grader Ari Rosensweig is fat, “so big that everyone stares.” (1) He is made fun of, bullied, called names. One time he is beat up, not even trying to defend himself. But he does make one friend, Pick, the only one who tries to learn the real Ari.

His parents fight. His mother is an artist, and the family moves frequently, his dad managing his mother’s art business. But when they move to the beach for the summer, Ari’s dad leaves and sees Ari infrequently.

There are times when you feel

like you can’t stop eating,

because eating

is the only way

you know

how to

feel

right

again. (67-68)

But that summer Ari makes two new friends. And as he has let the haters make him into who he is, he now allows Pick, Lisa, and Jorge help him “to find the real me.” (145) He also receives the support of the rabbi who is training him for his Bar Mitzvah, his conversion to manhood under Jewish law. “’Maybe,’ the rabbi says, ‘it’s as simple as believing that you don’t have to be what others want you to be.’” (225)

His mother suggests a diet, but it seems to be a healthy diet and he sheds pounds.

This doesn’t look like me.

It can’t be me.

I don’t look like this,

normal. (209)

On a camping trip with Jorge, Ari discards the diet book. “I don’t see a fat kid,

not anymore.

I simply

see

myself. (267)

Finally, even though he has gained back some of the pounds (7 of them), he no longer feels like a failure because "it’s not about the weight”; it is about what the summer has brought: adventures, stories, and real friends.

Just me moving forward,

finding my own way. (311)

Told in lyrical free verse, this is a story that is needed by so many kids. This is not a book about weight; it is the story of identity and friendships—and power over what you can control.

A golem is a creature formed out of a lifeless substance such as dust or earth that is brought to life by ritual incantations and sequences of Hebrew letters. The golem, brought into being by a human creator, becomes a helper, a companion, or a rescuer of an imperiled Jewish community.

Stan Lee once said, “If you don’t care about the characters, you can’t care about the story.” And I do look for characters I care about; in fact; sometimes I just want to take care of them. Even though I fell in love with them, there is no need in Chris Baron’s new verse novel; the two main characters, Etan and Malia, take care of each other quite well.

Etan is part of a close community of emigrés from Prague, the Philippines, China, and other countries who, with his grandfather, sailed on the Calypso and entered America through the Angel Island Immigration Center in 1940. Etan needs the support of his community when his mother goes to a mental hospital and he loses the ability speak—except sometimes. In addition, his father appears to have lost his Jewish faith, and the community Sabbat dinners end. Etan finds comfort in his religious grandfather and his jewelry shop which appear to be the heart of the community.

Etan doesn’t play with the other boys at school since his mother left, and, when on a delivery errand, he meets Malia who has been homeschooled since she was bullied and called “the creature.” Malia’s severe eczema keeps her in the house or covered up from the sun with her Blankie. However, as he becomes friends with her, Etan believes that his grandfather’s ancient muds will cure Malia’s condition or bring a golem to help them out.

Etan, there are many things

from the old world

from your ancestors

that we carry with us always.

It’s our fire. Our light.

But there are somethings from those times that are still with us. (114)

When the mud doesn’t work permanently, Mrs. Li tells Etan,

Your friendship for this girl is the oldest

and strongest form of medicine you can ever give her.

Remind her that she is not alone. (161)

His grandfather agrees,

…each of us has his own story.

You have a chance to be the light, to help a friend. (178)

Etan helps Malia find her voice, and, when the earthquake nearly destroys the city, the community joins together, and Etan former friend Jordan and the bully Martin also contribute.

At the same time, his grandfather acknowledges that Etan is nearing the age of thirteen, the age of Bar Mitzvah and becoming a man, and he gives Etan family artifacts that he had brought from Prague to “connect you to the old world like a bridge, to remind you of where you came from and who you are, and that anything is possible.” (298) This gives Etan the idea of how to help put things back together.

The old and the new mix together,

making something

completely new,

making something

together. (323)

Set during the October 17, 1989, San Francisco earthquake and the legendary Game 3 of the World Series between the Giants and the A’s, this story is magical but certainly not imperfect.

A memorable story of friendship, community, Jewish traditions, Filipino culture, and healing.

| Chris Baron: As an author, I want to write the stories I would have wanted as a kid. I wanted more stories about the quiet kids. The curious kids. The strong, resilient kids; the kids who didn’t always follow traditional roles (which I also think are very important). I wanted to see stories where the male character’s strength comes from kindness, empathy, hope, and resilience. I think the best stories come from the heart of who we are. When the LA Times called All of Me, “A fictional retelling,” I thought it was a perfect way to describe why I write about the challenges my male characters face. |

In one smooth move, like a plane taking off,

He leaped…

Higher and higher and higher--

As if pulled by some invisible wire,

And just when it seemed he’d have to come down,

No!

He’d HANG there, suspended, floating like a bird or a cloud,

Changing direction, shifting the ball to the other side,

Twisting in midair, slashing, crashing,

Gliding past the defense, up—up—above the rim.

Above the Rim is the story of NBA player Elgin Baylor and how he changed basketball, but it is also the story of Civil Rights in the United States and how Elgin contributed to that movement.

Readers follow Elgin from age 14 when he began playing basketball “in a field down the street” to college ball at the College of Idaho to becoming the #1 draft pick for the Minneapolis Lakers (later the LA Lakers) to being named 1959 NBA Rookie of the Year. At the same time readers follow the peaceful protests of Rosa Parks, the Little Rock Nine, and the African American college students sitting at the “whites only” Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC.

In his first season Baylor sat out a game to protest the hotel and restaurants serving “whites only,” leading the NBA commissioner to make an anti-discrimination rule. “Elgin had already changed the way basketball was played. Now by sitting down and NOT playing, he helped change things off court.”

“Artists [such as Baylor,] change how we see things, how we perceive human limits, and how we define ourselves and our culture.” (Author’s Note)

This picture book, exquisitely illustrated by Frank Morrison, belongs in every classroom and home library for readers of all ages. Lyrically written in free verse by Jen Bryant, it would serve as a mentor text for many writing focus lessons:

- repetition, free verse, and rhyming lines for musicality

- technical language (jargon), i.e., hanging jumper, spin-shot, backboard

- active verbs, i.e., gliding, shifting, floating, twisted, reverse dunked

- Figurative language, i.e., floating like a bird or a cloud

- Sensory details, i.e., steamy summer day, padlocked fences, clickety-clack trains, flick of his wrist, beds that were too short, cold food

Following the story, the author provides a lengthy Author’s Note about Baylor, a bibliography of Further Reading, and a 1934-2018 Timeline of Elgin’s life, black athletes, and Civil Rights highlights.

If you can read, you can do anything—you can be anything.”—Daisy Wilson

My father grew up in The Hill District of Pittsburgh; therefore, even though I am from a very different cultural background, I felt an immediate tie to August Wilson and his fascinating story.

Frederick August Kittle Jr., the son of a white German baker and Daisy Wilson, a black single mother who left school after sixth-grade, cleaned houses, and taught her four-year-old Freddy to read, overcame discrimination and poverty to become a Pulitzer prize-winning playwright.

Freddy left school twice when prejudice from classmates made it evident that he, the only black student, was not welcome in Central Catholic High and teachers at the public high school doubted his writing genius. Besides his mother, only Brother Dominic had faith in him, “You could be a writer.”

Freddy educated himself at the Carnegie Public Library though the works of such black writers as Hughes, Dunbar, Ellison, and Wright and the conversations of the Hill’s tribal elders—“warriors who survive in this hard world.” His job as a poet, and later as playwright, was “to keep [these voices] alive” though a collage of black characters from the Pittsburgh that never left him.

Through Jen Bryant’s verse biography, readers follow Freddy Kittle’s daily life as he grows into August Wilson, influenced by black writers and collage artist Romare Bearden and supported by fellow playwrights. Feed Your Mind, a picture book for MG/YA readers is hauntingly illustrated by Cannaday Chapman and includes a Timeline, Selected Bibliography, and list of Wilson’s plays.

| Jen Bryant: Two of my most recent picture book biographies (Above the Rim and Feed Your Mind) feature young men who found their respective “voices” through a lot of hard work, practice, trial and error and experimentation. Despite the fact that they expressed themselves through very different mediums, I was drawn to them because their lives began in a very ordinary way, but they ended up contributing to history in a profound and extraordinary way. In sharing their stories with young people, I hope that readers can see themselves in these young men and understand that greatness is a gift that is earned with passion, perseverance and courage. Although these young men lived at different times and grew up in different situations, each had a creative drive, a desire to challenge the status quo, and the courage to give a voice to those who needed to be heard. |

On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam collapsed. Twenty million tons of water from Lake Conemaugh poured into Johnstown [Pennsylvania] and neighboring communities. More than 2,200 people died, including 99 entire families and 396 children. [Author’s Note] The flood still stands as the second or third deadliest day in U.S. history resulting from a natural calamity.

Richard Peck wrote, “The bigger the issue, the smaller you write.” And author Ann E. Burg

introduces readers to individual residents of the town.

We read the stories of fifteen-year-old Joe Dixon who wants to run his own newsstand and marry his Maggie; Gertrude Quinn who tells us about her brother, three sisters, Aunt Abbie, and her father who owns the general store. We come to know Daniel and Monica Fagan. Daniel’s friend Willy, the poet, encouraged by his teacher to write, and George with 3 brothers and 4 sisters who wants to leave school and help support them. We watch the town prepare for the Decoration Day ceremony honoring the war dead.

And after the flood, readers hear from Red Cross nurse Clara Barton, and Ann Jenkins and Nancy Little who brought law suits that found no justice, and a few of the 700 unidentified victims of the flood.

And there are the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club—Andrew Carnegie, Charles J. Clarke, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, Cyrus Elder, and Elias Unger, the wealthy of Pittsburgh who ignored repeated warnings that the dam holding their private lake needed to be repaired so it wouldn't give way. “They don’t care a whit about the likes of us.” (57)

This is a story of class and privilege and those who work tirelessly to make ends meet. As Monica says, “People who have money, who shop at fancy stores and buy pretty things, shouldn’t think they’re better than folks who scrabble and scrounge and go to sleep tired and hungry.” (111)

In free-verse narrative monologues, readers experience the lives of a town and its hard-working, family-oriented inhabitants—people we come to know and love, reluctant to turn the pages leading towards the disaster we know they will encounter. We bear witness to the events as we read and empathy for the plights of the people affected by those events.

This is a book that could be shared across middle grade and high school ELA, social studies, and science classes.

| Ann E. Burg: All of the characters in Flooded, Requiem for Johnstown were based on real people who were living in Johnstown at the time of the flood. There were 2,209 people who died in the flood— including 396 children and 99 entire families. 750 victims were never identified. I studied the names of these victims and whatever scant description was noted in the morgue books. Then I let the names sit with me as I read about life in Johnston in 1889 and the struggles faced by the survivors of the flood. The challenges my characters faced were the challenges inherent in the day to day life of an industrial town and the struggles of immigrants working toward a piece of the American dream. |

“Getting As in all my classes is SO much easier than all the personal stuff. I wish friendship came with a textbook.… School would be so much easier without all the non-school stuff.” (Drew, 169)

In the sequel to New Kid, seventh grade friends Jordan, Liam, and Drew have to learn to navigate a new year in their prestigious private school. But eighth grade becomes much more complicated.

Jordan, who is struggling with being younger, smaller, and more physically immature than the other eighth grade boys, has to keep the peace between his best friends when Drew visits the mansion where Liam lives, judging him for how his parents’ lifestyle. Liam, whose parents ignore him, knows that wealth is not the secret to happiness.

As the boys visit each other’s neighborhoods and meet kids from another school which RAD wants to adopt as a “sister school” to promote diversity, they begin to notice microaggressions, racism, and classism all around them. Their “ever-learning and ever-evolving” school creates an Office of Diversity and Inclusion and also a Students of Color Konnect club, and things become worse. “No one is happy just being who they are. It’s like we all have the way we want people to think we are…and then we have our real selves.” (177)

When Jordan’s parents get involved in day of food and sports, all three boys become exposed to new experiences. And they—especially Drew—realize, “We should probably try to stop being so hard on each other.…And on ourselves.” (244)

Jordan the aspiring cartoonist continues to share his life through black and white drawings within each chapter.

There was no backup plan. All the worlds would fall under Somni control if someone didn’t stop the priests. Apparently, that someone was [Griffin].” (150)

“She was only herself. Stubborn, impatient, all-too human Fi. How could she be any different? But Great-Aunt Una had believed she could be more. Was that why Eb had stepped in front of the blow meant for her because there was supposed to be something special about Fi? Something she could do to save Vinea that no one else could?” (116)

In Melanie Crowder's new novel, A Way Between Worlds, readers meet the ultimate resilient boy—and girl. Readers first meet fifth-grader Griffith who has to travel to another world to save his father in The Lighthouse Between the Worlds where we also meet Fiona, a young Vinean resistance fighter who is living on Somni and grieving the loss of her family and her world.

But their strength and heroism is tested in this sequel. In Crowder’s universe, Vinea, the land of greenery; Caligo, a world made of air; Maris, where water and song intertwine; and even Earth where all elements work together, are invaded by the wicked priests who control the minds of the armies on Somni and “use that power to attack and colonize every world in their reach.” (3)

Through the two books, readers are witness to Griffith’s growth as he travels the hero’s journey. As Fi observes, “When he first showed up on Somni, he did everything wrong—I thought he was going to bring the whole resistance down.…But he was so sure that was exactly where he needed to be….” (128)

Readers also share Fi’s journey as she discovers her powers and recognizes and nurtures the powers of others.

Separately, on different worlds the two young adolescents take risks to save the all worlds, not only “theirs.” “It doesn’t matter what world we’re from. If we don’t stand together sooner or later they’ll come for us all.” (159)

This novel is a true sequel and cannot be understood without reading The Lighthouse between the Worlds, but who would not wish to spend two novels’ worth of time immersed in lovely, powerful language which provides a visual experience, with delightful characters who expand their idea of family to encompass the peoples of five worlds.

Four rising 7th graders. Video Gamers. Divergent thinkers assigned to a summer school class. And a teacher who needs to teach them to read well enough to pass the FART (Florida Rigorous Academic Assessment Test), a teacher who is willing to meet her students half way, a teacher who shifts from a Teacher Griefer to a Gaming Legend, a teacher who learns that mastering Human Being Assessment Test skills is more important than Reading and Writing Assessment skills.

•Benjamin Bellows aka Sandbox Gamer Ben Bee whose weak writing skills are overcome with a 504 Plan and a typewriter. “”I’ve been thinking: finally something to help me do better, not Why now, not what’s wrong.” (206)

•Benita Ybarra aka Sandbox Gamer ObenwhY who is struggling with grief and loss. “But when you crash your car, you don’t have extra lives saved, stored up, hoarded. You have nothing that can blink you back to life.” (189) but who learns to trust and heal “I look up at her, as I pull this moment even tighter, a soft blanket of now becoming a bandage holding together the crack in my heart.” (191)

•Jordan Jackson aka Sandbox Gamer JORJORDANJMAGEDDON, diagnosed with ADHD, friendly, funny, and obsessed with a television dance contest show—and with Spartacus.

•New student Javier Jimenez aka Sandbox Gamer jajajavier who has a secret as to why he hides behind a hoodie and refuses to read aloud. “I think I finally have friends” (266)

•Teacher Jordan Jackson (no relation) aka Sandbox Gamer JJ11347 whose job is in jeopardy after she allows the students to read a book based on Sandbox instead of Oliver Twist, a divergent teacher.

you’re right, though

she’s a divergent teacher

she teaches differently

she, like, listens to us. (247)

Four kids who become “Not besties. But not nothings.” (211) Four children who I fell in love with as they discover their strengths individually and together through the willingness of a teacher to become a learner.

Written in the students’ four voices in free verse, stream-of-consciousness, and drawings, and through game chats, the story will appeal to divergent upper elementary and middle-grade readers.

| Kari Anne Holt: I asked Kari Anne how have her novels changed in the last few years to reflect current adolescent life and experiences? Very early in my writing career, I worried a lot about getting my readers to easily relate to the characters I created. At that time, I fell into the trap of thinking that fast-paced action and well-placed fart jokes would do the trick. It didn't NOT do the trick, but it also didn't move beyond creating a more surface-level relatability. Again, not a bad thing, but I began asking myself, as a writer, as a storyteller, as a mother, as a citizen of the world... how could I do better? |

Boys have feelings. Full stop. They cry. They hurt. They yearn. They love. They can laugh and cry in the same moment. They can love and hurt in the same breath. And they deserve to know that, much like farting, these are healthy, universal expressions that cross all genders.

Twelve-year-old Trace’s world changes when his older brother Will is injured in a high school football accidental collision with another player. Luckily, he was not paralyzed,

But his brain had volleyed

Between the sides of his skull

So hard it was swollen. (14)

Will is left with rages, headaches, and a “wrecked” facial nerve leaving him with no expression except for a facial tick. Their mother blames their father for letting Will play football and their already-fragile marriage dissolves when she leaves for a permanent tour with her band. “When you’re scared, blame comes easy.” (13)

Will changes, dumping his loyal girlfriend and hanging out with new friends—a seemingly bad crowd who he sneaks out to join at all hours, and Trace is left without the big brother he remembers.

Probably what I miss

most of all, though,

is having a big brother

to talk to. Some things

you can’t tell just anyone. (18)

Luckily Trace has Bram, his best friend, and a new friend, Cat, the newest member and only girl (and maybe best player) on Trace’s Little League team and his new partner in the Gifted program at school. Cat has a troubled older brother and empathizes with Trace. When Cat’s father, the famous baseball player Victor Sanchez, signs Trace’s glove, Will steals and pawns it. In fact, Will has stolen all of Trace’s saved money, and Trace becomes suspicious of Will’s “activities” but is hesitant to bother his father who works hard and has a new girlfriend.

Also

I keep thinking if I

keep his secrets

don’t tell Dad

don’t bother Mom

he’ll trust me enough

to tell me why he hardly

ever leaves his room, and where

he goes when he ducks

out the door the minute

Dad’s back is turned.

I miss the original Will. (25)

As things become worse, trace realizes,

I need someone here for me…”

I feel like a kite

Come loose from its string

And its tail tangled up

In a very tall tree.

No way to rescue it

Unless a perfect w

Whisp of wind

Plucks it just right, sets it free. (333)

When Will overdoses (mistake? suicide attempt?), everyone—Dad, Lily, Mom, Mom’s boyfriend, their neighbor, Cat, and Bram—comes together and support not only Will but Trace.

“Maybe Pap isn’t the person I’ve been trying to impress all this time. Maybe it was me. Maybe what I really need is to be proud of myself.” (236)

A 13-year-old drag queen; a rising comic learning the difference between insults and jokes; a three-legged blind rescue dog; a wheelchair-bound Super Hero impersonator; a dream interpreter; two best friends that offer support no matter what—and, right in the middle, their Talent Agent, rising entrepreneur Michael Pruitt of Anything Talent and Pizzazz (not Pizza) Agency.

Seventh grader Mikey (as he is called when he is out of the office) has been planning businesses, most of which have failed, to impress his beloved Pap, the original family entrepreneur who is now in a nursing home with diabetes and heart problems. His Board consists of his very supportive mother and father and his less-supportive, evil, client-stealing younger sister, Lyla. When Mickey meets Coco Caliente, Mistress of Madness and Mayhem (boy name Julian Vasquez) at school, he has found his new business.

Mikey thinks he might be—no, he knows that he is—gay, but he has only come out to his parents (“They were wicked cool about it right from the beginning.” (30)) and his two best friends although, for some unfathomable reason, the school bullies call him Gay Mikey. However, he worries that he is not good at being gay, has no gaydar, and is sure that he is not ready to like-like someone. Then he meets Julian’s friend, new student Colton Sanford whose smile makes his stomach melt. Julian, who has become a friend, tells him, “Michael, there’s no right or wrong way to be gay.” (95)

Michael spends the next weeks Googling performance terms, trying to book paying gigs for his clients, and preparing them for the school talent show where he can earn a commission if a client wins the $100 prize. And navigating the school bullies.

As Mikey, he discovers the secret of head bully Tommy Jenrette which ends up improving their relationship, and he supports Julian’s whose mother and abuela are encouraging but his father absolutely forbids him to dress up. “I just wish my dad could be proud of me,” Julian says, his shoulders sagging. “Like he used to be—before Coco Caliente.” ((94)

Mikey also encourages and defends Colton who tells him that he moved in with his grandmother because his mother is in rehab. “I guess you just never know what’s going on with someone, even if they seem okay and wear a mask that’s nice to look at.” (231) Mickey is good at letting his friends appreciate that they matter. “I think about my business ventures and how they make me feel important. And like I matter. And wanting to matter doesn’t seem like too much to ask.” (94)

The characters, especially Mickey/Michael, grabbed me on page 1. “I think CEOs of big-time companies like mine shouldn’t be required to attend middle school. It seriously gets in the way of doing important business stuff.” I have been reading many wonderful important MG novels, but Middle School’s a Drag is hilarious, the writing voice jumping right off the pages. I didn’t put it down, and neither will readers. This is a book for reluctant readers, proficient readers, and the many adolescents who need to know that they matter.

| Greg Howard: All my books have some percentage of “me” in them. I borrow from my life as a kid quite often. Mikey in Middle School’s A Drag; You’d Better Werk! grew out of my memories having that entrepreneurial spirit I had at his age. The “businesses” Mikey started prior to becoming a talent agent for his school friends were all things I created in my dad’s office/storage/laundry room—the general store, the croquet instruction, I did all that and more. I tend to write about male characters who are navigating situations like what I went through growing up as a closeted queer boy in the South—unrequited crushes, religious oppression, hiding who you are all the time, etc. While a lot of kids’ experiences today are different than mine, I hear from many young readers whose life situations are not that different at all. I want the marginalized and othered kids out there to feel seen, represented, and to know they’re not alone. |

“No one chooses to be a refugee. To leave their homes, family, and country.” (Omar Mohamed’s Author’s Note) At least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. (UNHCR.org)

Omar and his younger brother Hassan spent 15 years in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya, leaving their home in Somalia when Omar was 4 years old. Their father had been killed and mother left, not returning before the villagers were compelled to flee the violence, taking the boys with them. This is Omar and Hassan’s story, beginning after 7 years living in the camp with Fatuma, their appointed foster mother, also a refugee.

It is the story of Omar who was encouraged to begin school at age ten and found hope in education. Though it was challenging to take care of Hassan, chores, and studying, he earned his way into middle school and then high school.

It is the story of his brother Hassan who had seizures and did not speak but was kind to children and animals and watched over by the camp community.

It is the story of the girls of the camp, especially Nimo and Maryam, and the restrictions and expectations placed on girls by their society.

It is the story of the camp refugees and constant hunger, deprivation, and despair but also the joyful celebrations of holidays and traditions and the hope for reunification with family and resettlement in a safe country. And dreams.

“None of us ask to be born where we are, or how we are. The challenge of life is to make the most out of what you’ve been given. And despite all the things I don’t have…I have been given something very important. The love of others is a gift from God, and it shouldn’t be taken for granted.” (212)

Omar’s story, co-written and illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, is a graphic memoir that comes alive through the drawings. It includes an Afterword that takes readers from the story’s ending in 2009 to Omar and Hassan’s life today. This novel will be an important introduction to many readers to a life their peers may have experienced. Hopefully it is a story which will lead to understanding, compassion, and respect. As Omar’s middle school English teacher tells them, “Throughout your life, people may shout ugly words at you like, ‘Go home, refugee!’ or ‘You have no right to be here!’ When you meet these people, tell them to look at the stars, and how they move across the sky. No one tells a star to go home.” (120)

“You jump and it’s over, pain gone, nothing more to say.” (250)

Two adolescents and two possible outcomes equals four possibilities. In two of these scenarios, Aaron exhibits strength and resilience.

Tillie and Aaron are New York City teenagers who are experiencing depression and despair. Even though they have never met, they both decide to jump off the George Washington Bridge coincidentally on the same day at the same time. The possibilities: Tillie jumps, Aaron sees her and lives; Aaron jumps, Tillie watches him and lives; both jump and both die; Aaron and Tillie see each other preparing to jump and meet, neither jumps, and both live.

This exquisitely-designed narrative shares all four scenarios as readers become progressively involved with the two characters, their families, and their friends and acquaintances. Even though readers are reading different permutations of the story, it is so well-crafted that there is little repetition as the stories develop.

As readers experience the world through Aaron’s and Tillie’s eyes, we learn about depression, suicidal ideation, and the immeasurable importance of connection with others. Readers perceive the effect of suicide on those involved in the lives of the victims and realize the significance of discussing feelings of despair and exploring alternatives to suicide.

“People are like that [the power of water] too. And love. Life-saving and life-taking, and it’s almost too much to navigate, that there’s this thing out there we need so much, that also hurts and destroys as it does.” (323)

Bill Konigsberg’s latest novel should be included in all secondary school and classroom libraries and included in book clubs where readers can discuss in small groups.

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

Everything Sad Is Untrue is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

| Daniel Nayeri: Everything Sad Is Untrue is a memoir; therefore, I asked author Daniel Nayeri why he wrote about his experiences and the challenges faced. I have always loved a definition of "coming-of-age" stories that I heard from Gary Schmidt. He said they were an expression of the moment when a child "turns their face toward adulthood." I think a story like Everything Sad Is Untrue could be a brutal slog through a tale of immigrant woe, or it could be a coming-of-age, a blueprint for young readers on how one particular refugee kid in Oklahoma, with a whole lot of chaos in his life, started to find the tools necessary to work through that chaos and turn his face toward adulthood. I tried to make it the latter. |

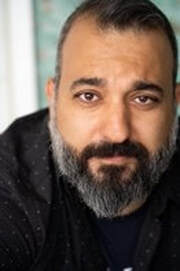

On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry. This was supposed to be a great year. “I guess it won’t be after all.” (25)

When his friends all join the football team, Rex has no one to sit with at lunch. “Having a place to sit in middle school is important. ‘Cause it means you have friends. Popular kids sit at one table. Football players sit nearby. Cheerleaders too. Band kids are in one area, school newspaper and yearbook kids at another. Religious kids have a table. So do the kids who play Dungeons & Dragons. The whole cafeteria is that way. Everyone has their place. Everyone except me.” (56)

As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor. “I don’t get why folks act like being poor is a disease, like it’s wrong or something.” (53)

On the positive side, Rex makes a new friend at school, Ethan, a boy who may have seems a “total weirdo” at first but turns out to be a good person and true friend and have his own family problems, and Rex’s teacher learns to admit and face her own prejudices. Rex comes to the realization that “Mom didn’t sign me up for the Free Lunch Program to punish me. She did it so I could have food….Things are not as black and white as I thought. Maybe some things are gray, somewhere in between.” (188)

Rex’s mother finally obtains a job, and he even receives a present for Christmas. “I may not have a million presents, but I have one. And one is better than none.” (188) As Ethan tells him, “…no one has a perfect life. There is no such thing as ‘perfect.’ It’s just an idea.” (195)

.

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in families who earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them—and Free Lunch is his story.

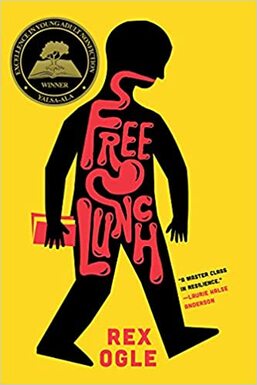

Becoming Muhammad Ali relates the story of boxer Cassius Clay from the time he began training as an amateur boxer at age 12 until he won the Chicago Golden Gloves on March 25, 1959—with glimpses forward to his 1960 Olympic gold medal and his transformation to Muhammad Ali.

The novel is creatively co-written by two authors in the voices of two narrator-characters: James Patterson writes as Cassius’ childhood best friend Lucius “Lucky” in prose and Kwame Alexander writes in verse, sometimes rhyming, most times not, as Cassius Clay. Dawud Anyabwile drew the wonderful illustrations.

Cassius Clay’s grandaddy always advised him, “Know who you are, Cassius. And whose you are. Know where you going and where you from.” (25) and he did. From Louisville, Kentucky, from Bird and Clay, and (in his own “I Am From” poem) from “slavery to freedom,…from the unfulfilled dreams of my father to the hallelujah hopes of my momma.” (28-29)

Readers learn WHY Cassius Clay fought,…

for my name

for my life

for Papa Cash

and Momma Bird

for my grandaddy

and his grandaddy…

for America

for my chance

for my children

for their children

for a chance

at something better

at something way

greater. (296-297)

As Lucky tells the reader, “He was loud. He was proud. He called himself the Greatest. Even when he wasn’t. Yet. But deep down, where it mattered, he could be very humble. It was another part of him that he didn’t let most people see.” (231) “He was also a true and loyal friend.” (305)

Throughout the novel, readers also learn boxing moves, information about famous boxers, such as Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano, and matches, and even more about the person who was Cassius Clay and became Muhammad Ali.

“However, I came to the conclusion a long time ago that people often see only what they expect to see. If they don’t expect much, they don’t see much.” (99)

When we accept those who see things differently, we begin to see things in a different way.

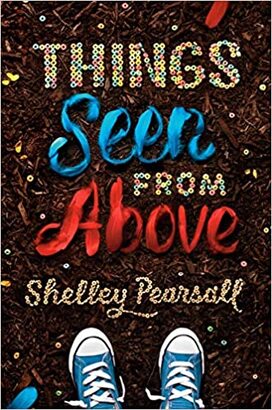

Sixth grader April feels like a misfit when her former best friend shows up at school with a new look, new clothes, and new friends. She avoids the 6th grade lunch by volunteering to staff the Buddy Bench during that time which is also the 4th grade recess. During recesses she observes Joey Bird, a 4th grader who doesn’t play with any other kids and appears to spend the time dragging his feet randomly through the wood chips and sometimes lying down in the midst of them. April thinks Joey may have autism and, as she observes him during the school day, it also seems as though he cannot read and frequently gets kicked out of class.

But as April and her fifth grader helper, Veena, a new student from India, observe more closely, they realize that Joey is actually creating spirals and even intricate drawings in the chips. Their observations are verified by Mr. Ulysses, the custodian, an inventor himself, who has been taking photographs of Joey’s art. April and Veena elect to get to know Joey and the meaning of his art.

When their discovery is accidently shared with other students, they all begin to look at Joey, and each other, differently. “Joey’s popularity seemed to pull other forgotten kids out of the shadows.…The outcasts started getting noticed. The excluded were included.” (146)

People even start seeing Joey’s art in different ways. “Our outlines kept moving and changing every day—and there was no telling who we would eventually become.” (191)

In first person chapters narrated by April and third person chapters written from Joey Bird’s perspective, augmented with his artwork, readers will be led to think about what they see and how they see—themselves and others in this important tale of assumptions and acceptance.

“Be you. Stay confident, visible. Even if others can’t see you.” (183)

Trey and Donte are biracial brothers, but Trey looks like his White father and 7th grader Donte takes after his Black mother. This didn’t seem to matter in their public school in NY where they both had lots of friends, but at Middlefield Prep in Boston, it does. Trey is a popular and respected athlete while Donte is taunted and bullied. Trey stands up for Donte when he can “Ellison brothers stick together” (47), but Alan, the school bully, leads his followers in a chant of “black brother, black brother.” It’s Alan who and wants “other students to see only my blackness. See it as a stain.” (34) and makes “me being darker than my brother a crime.” (44)

When Donte complains, “Everyone here bullies me. Teachers. Students. Whispers, sometimes outright shouts follow me.” (6), not only is Headmaster McGeary not sympathetic, he blames and even punishes him for crimes he has not committed. “Why can’t you be more like your brother?” (8). He calls the police and has Donte taken to jail for slamming his backpack at his own feet in frustration. Released from jail, his mom, a lawyer says, “This is how it starts. Bias. Racism. Plain and simple…” (24)

One option is to “Disappear. Be invisible.” (19), but Donte vows to beat Alan at his own game—fencing. With Trey’s help, he discovers Arden Jones, an African American Olympic fencer who works at the local Boys and Girls Club, and convinces Mr. Jones to coach him. As Donte gets stronger with the help of Coach, Trey, and his new friends at the Boys and Girls Club, he begins to regain a trust in people. “Prejudice is wrong. Wrong, it makes me doubt people.” (87) He learns his Coach’s history and how it is easy to lose oneself in people’s hatred. As Coach tells him when relating his own past failure, “I quit playing because I gave up on me. Became invisible.… Should’ve kept focused on my goals. Should’ve known bullies, biased people, can’t see clearly.” (182) His advice, “Don’t do anything for anyone else, Donte. Do it for you. Only you.” (131)

And most important, through fencing, Coach, his supportive family, and his new friends, Donte learns that he wants to fence, no longer to beat Alan and humiliate him but “to be the best.” (183)

Another powerful novel for 4th though 8th graders by Jewell Parker Rhoads, author of some of my favorite novels, Ninth Ward, Towers Falling, Paradise On Fire, and Ghost Boys, this short novel, as did Ghost Boys, tackles racism—by adolescents, adults, and society‑head on. The sport of fencing, tied to honor and nobility and promoting good sportsmanship, is particularly appropriate; every fencing bout starts with a salute to your opponent and ends with a handshake.

| Jewell Parker Rhodes: Donte grew out of my research for Ghost Boys. Racism and bias can exist not only in communities but within schools. I also wanted to use the relationship between brothers to demonstrate how skin color causes negative perceptions about Donte but his brother, Trey, who is white-appearing, is treated respectfully. My goal was to show the ills of colorism and how skin tone is a superficial difference. Genetically, we are all one race—human. |

“There was a time I thought getting older meant you’d understand more about the world, but it turns out the exact opposite is true.” (296)

Jason Reguero has his life planned out, at least as much as any typical 17-year-old. He will finish his senior year, play video games with his best friend Seth, attend Michigan in the Fall, graduate, and get a job, even though he has no idea what he wants to do and has not found anything that has awakened a passion.

In fact, Jay seems somewhat adrift until he receives the news that his seventeen-year-old cousin, Jun, was killed in the Philippines by government officials under President Duterte’s war on drugs, accused of being a drug addict and pusher. Jun’s father, as head of the police force, refuses a funeral or any type of memorial.

The last time Jay saw Jun was when his family, whose family had moved to the U.S. so the three siblings could be more “American” like their mother, was when they were ten and were like brothers. They had written back and forth until Jay got caught up in his own life and stopped answering Jun’s letters. Jun, questioning the political regime and the church, had moved from his restrictive father’s house and was thought to be living on the streets. Feeling guilty for having abandoned his cousin, Jay uses his Spring Break to fly to the Philippines to investigate Jun’s death, the reason he was really killed, and why no one—other than his sisters, Grace and Angel—mourns his death.

Jay is introduced to Grace’s friend Mia, a student reporter, and together they investigate Jun’s last few years. They find that Jun’s story is not that simple. “I was so close to feeling like I had Jun’s story nailed down. But no. That’s not how stories work, is it?. They are shifting things that re-form with each new telling, transform with each new teller. Less a solid, and more a liquid talking the shape of its container.” (281)

Ribay’s coming-of-age novel, Jay finds some answers, and some more questions, challenging his preconceptions. But he also begins discovering his Filipino heritage and his identity as a Filipino-American. He finds a passion which determines his future—at least for now.

“We all have the same intense ability to love running through us. It wasn’t only Jun. But for some reason, so many of us don’t use it like he did. We keep it hidden. We bury it until it becomes an underground river. We barely remember it’s there. Until it’s too far down to tap.” (265)

This is a YA novel for mature readers about identity, family, heritage, and truth. Readers will also learn a lot about Filipino history and contemporary politics.

“What about the boys on the other side of the wall? Picking whatever activities they’d like because they were born into families who can pay their tuition. [The headmaster] is right. I’m lucky. But it’s hard to feel that way right now.” (ARC, 50)

Omar lives in a one-room hut with his mother, a servant for the family of Omar’s best friend Amal. When Omar is accepted to the prestigious Ghalib Academy for Boys as a scholarship student, his whole town celebrates. He is aware that his future opportunities have widened, but he is particularly excited about the extracurricular activities, especially the astronomy club since he has always wanted to be an astronomer.

At school Omar immediately makes friends—Marwan and Jabril from Orientation; Kareem, his roommate and one of the scholarship kids along with Naveed, and soon others, especially when they observe Omar’s soccer skills. The only unfriendly person appears to be their neighbor Aiden. And Headmaster Moiz, the English teacher for the scholarship students or, as he says, “kids like you,” who appears to take an instant dislike to Omar. Despite having the academics to be accepted, the scholarship kids find the studies difficult, no matter how hard they study.

And then they find out that Scholar Boys are not permitted to join any activities or sports; instead they have to do hours of chores.

“Back home, everyone was proud of me.

Back home, everyone was jostling for me to be part of their team.

But I’m not home now.” (ARC, 56)

“I’m the kid doing chores. Who can’t do any of the fun after-school activities. Struggling to keep up with my classes.” (ARC, 153)

Omar and Naveed and the others fulfill their work hours, manly in the kitchen with the chef Shauib and his son Basem where Omar finds he has some talent and where they can keep their secret from the other students (who think they are just nerds, studying all the time). “Marwan acts like we think being stuck in a room on a Friday night instead of out having fun is what we want to do. He doesn’t get it. Because he can’t.” (ARC, 109)

But the boys find out that the system is rigged. Most of the Scholar Boys are not expected to stay beyond the first year. Studying together with the other scholarship boys, night and day, Omar does well in science and math but continues to do poorly in English until he asks the Headmaster to tutor him.. “Finding out how hard it was to actually stay at this school, I’d started pushing away my dreams, afraid it would hurt more if it all crashed down. But maybe holding onto your dreams is how you make your way through.” (ARC, 117) But he finds it is notenough.

For his art class final project, Omar studies Shehzil Maik, a local artist who works in many mediums to promote justice, equality, and resistance. With her influence, he designs his own collage “Stubbornly Optimistic.” During his presentation Omar shares the injustice he and the other Scholar Boys are facing. “We might go to the same school, but the rules are completely different for us.… We might be in the same classes but we are from different classes.” (ARC, 176)

“The driver hit the gas and the tires squealed as the truck made a sharp turn and then accelerated right though a bombed-out warehouse onto a parallel alley. Fadi looked from the edge of the truck’s railing in disbelief. His six-year-old sister had been lost because of him.” (25)

Fadi’s father, a native Afghan, received his doctorate in the United States and returned to Afghanistan with his family five years before to help the Taliban rid the country of drugs and help the farmers grow crops. But as the Taliban became more and more restrictive and power-hungry and things changed, Habib, his wife Zafoona, Noor, Fadi, and little Mariam (born in the U.S.) need to flee the country. During their nighttime escape, chased by soldiers, Fadi loses his grip on Mariam as they are pulled into the truck, and she is lost.

Eventually making it to America, the family joins relatives in Fremont, California. “Fremont has the largest population of Afghans in the United States” (56), and Habib takes measures to try to find and rescue Mariam. Starting sixth grade in his new school, Fadi is continuously plagued with guilt over Mariam’s loss and is tormented and beaten up by the two sixth-grade bullies.

However, though Anh, a new friend, he joins the photography club and becomes obsessed with a contest that could win him a ticket to India for a photo shoot but also take him in proximity to Pakistan where he can look for Mariam himself.

Then the events of September 11, 2001, occur and “By the end of the day, Fadi knew that the world as he knew it would never be the same again.” (137). Harassment escalates both at school and in the community. “[Mr. Singh] was attacked because the men thought he was a Muslim since he wore a turban and beard. They blamed him for what happened on September eleventh.” (165)

When the Afghan students have had enough with the school bullies, they band together and confront the two boys, but having them cornered, decide, “We can’t beat them up. That would make us as bad as they are…. Beating them up won’t solve anything.” (232)

Meanwhile, while looking for a photograph that will capture “all the key elements” of a winning photograph and additionally portray his community, Fadi shoots the picture which, in an unusual way, leads to finding Mariam.

Shooting Kabul introduces readers to one family of refugees living in a community of Afghans of different ethnic groups as well as immigrants from other countries. The story also takes readers through some of the background of the Taliban in Afghanistan, relevant at this time.

Illegal is the winner of the 2021 International Latino Book Award - Gold Medal

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to first read Disapppeared, but it would surely enhance the reading.

“Respect and disrespect. Killing and revenge and cowardice. Stupid, meaningless words, all of them. None of them worth dying for.” (270)

Hector and his family were still grieving the loss of his father to cancer, his brother dealing with it through drinking. But Hector was a good, smart kid on his way to a better life. Then things were finally looking up; Fili was drinking less, in love, and planning to buy a house to move the family out of the projects where Chavo, the drug dealer, and his brother Joey ran things. What would induce Hector, a chess team champion, writing contest winner with college aspirations, who worked a grocery job to help his mother pay the bills, to confess to a crime in order to end up in reform school.

At school and home in the projects, Joey threatens to kill Hector, carving a “C” in Hector’s chest, and Hector becomes consumed with the shame of his own cowardice. When Joey kills Fili, he and Hector are sent to the same reform school, where Hector has to decide how to make things “balance[d]” as decreed by the apparition of his father. Should he humiliate Joey in the boxing ring and then kill him? Will those acts make him less of a coward? Or does he listen to his many mentors?

“X-Man went suddenly quiet. He looked as if he was remembering something painful. ‘Dude, you gotta find a way to move on. When your flashlight’s stuck like that, you’re not seeing, like Mr. Diaz says. And seeing’s the only way to free yourself.’” (214)

Francisco Stork’s newest novel is filled with 3-dimensional characters who jump off the page into the reader’s heart. I felt protective of Hector, wanting to cheer him on and shake him and counsel him. I grieved for Fili and his lost future as if I had known him. Even Joey, the villain, came alive as his story validates the idea that everyone has a back story and their own demons.

Maybe the balance Hector needs to create is in himself.

This is a story that many adolescents need to read as books can be “mirrors” or “windows” but can also provide maps. Christopher Myers wrote, “They [the children I meet in schools visits] see books less as mirrors and more as maps. They are indeed searching for their place in the world, but they are also deciding where they want to go. They create, through the stories they’re given, an atlas of their world, of their relationships to others, of their possible destinations.” (The Apartheid of Children’s Literature,” Sunday Review, The NY Times).

| Francisco Stork: Emiliano, the main male character of Illegal, struggles with the natural human need for belonging. It is not just the new language, country and people that are foreign, but also that knowledge that he is unwanted. He is not fully accepted even by his americanized father. Emiliano overcomes his loneliness by dedicating his life to save his sister and other victimized young women. This sense of purpose eventually leads him to find a place where he is welcomed. |

Kabir Khan, the son of a Muslim father and Hindu mother, was born behind bars in a prison in Chennai, his mother wrongly accused of a theft before he was born. He has lived his life in deplorable conditions—little food, no privacy, intermittent water availability, and no freedom. His only happiness is being with his Amma and his teacher at the prison school.

But at age 9 his life becomes even more uncertain when, too old to live in prison, he is to be released into the streets. “I tell myself I’m free. I’m outside where I dreamed of going, but I feel like a fish in a net being lifted out of the water I’ve lived in all my life.”(59)

Claimed by a man who says he is his uncle, he faces his first dangerous situation. “My ‘uncle’ is selling me.” (72)

Kabir escapes and navigates the streets with the help of a new friend, the resilient Rana, an adolescent girl who has lived on the streets —and in the trees— and killing her own food—squirrel and crow stews—since her Kurava (Roma) family was attacked, her father killed. She teaches Kabir how to survive street life. He has two goals: to find his father and find a lawyer to release his mother from prison. “I can just imagine Amma walking out of that gray building—me holding one of her hands and my father holding the other.” (93) His command of both Kannada and Tamil languages are an asset and when following his Amma’s wishes to be good, he returns a lady’s lost earring, he and Rana and rewarded with tickets to Bengaluru to find his father’s parents.

In Bengaluru Kabir and Rana learn to trust and find new lives that allow them to both have hope again.

Filled with memorable characters, this emotional story will bring empathy and cultural awareness to upper elementary/middle-grade readers; its short chapters will provide a good read-aloud for teachers, librarians, and parents.

| Padma Venkatraman: The book is inspired by true events that occurred. I read a BBC news report in 2013 about a boy who'd been born in jail in India to a mom who was low-caste and too poor to post bail. So in a way I didn't choose the gender of the main character; it came to me that way. I started hearing and then seeing this boy in my imagination—a kid who'd been locked up the first few years of his life and is then set free while his mom remains behind bars. I could feel their bond of love. I could sense how he was naive because he'd never been outside jail; how this naivete would actually help him decide to try and fight entrenched prejudice and systemic racism to try and free his mother. The characters came alive—his mother is able, because of him, to preserve her kind nature even though she feels her situation is futile and beyond help. She's given up on ever being rescued, but she hasn't given up on the idea that her kid will be a hero—and that's what gives him resilience and strength. |

Check Out the Slide Show!

A nice tool you can use to book talk with your students

Lesley is the author of five professional books for educators on reading, writing, and grammar:

- Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core

- Comma Quest: The Rules They Followed. The Sentences They Saved

- No More “Us” & “Them: Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect

- The Write to Read: Response Journals That Increase Comprehension

- Talking Texts: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum

- and has contributed chapters to four anthologies:

- Young Adult Literature in a Digital World: Textual Engagement though Visual Literacy

- Queer Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the English Language Arts Curriculum

- Story Frames for Teaching Literacy: Enhancing Student Learning through the Power of Storytelling

- Fostering Mental Health Literacy through Adolescent Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed