| Christian Gregory is an Assistant Professor at Saint Anselm College, teaching courses for preservice teachers in methods, pedagogy, the graphic novel, and Young Adult Literature. He has written chapters on the history of both YAL and the graphic novel and published in English Journal, English Education, the Journal of LGBTQ Youth, and the International Journal of Dialogic Pedagogy. His research interests are diversifying the canon, dialogical theory, and queer studies. |

Responsive to this population of fans and athletes, I have adjusted my curriculum accordingly. In my course Adolescent Literature, I have been inspired by the work of literacy scholars who trumpet the need for student book selection, which they deem essential for engagement, literacy, and student success (Buehler, 2016). For the instructor, this “savy and strategic matchmaking” (p. 87) is key; yet for some classrooms, teachers may not wish to sacrifice the benefits of collective discussion for small group reads. How then can we allow for student choice while inviting topical conversation?

My response is March Madness pedagogy. I invite students team up for reads in teams of two, three, or four, and select book of interest to them within an All Sports Read (See list of possible titles for your classroom next week, in Appendix I). I do suggest a curated list by the instructor. Last year, I provided titles I thought offered diversity of race, gender, sexuality and culture. Each student was allowed to select from the curated list, and no student was allowed to read alone. This program of study was to ensure another reader of each title in class: to both encourage completion and bolster discussion in small groups. Small group reads in middle and high school are nothing new in curriculum, but whole class discussions on topic may be less so. Were a classroom teacher to take this on as a practice, an all-sports read, I would like to offer a pedagogy that respects the differentiation of titles while embracing common themes.

One way to invite students into small group discussion is to focus on the athlete and their relation to the sport or their identity as an athlete. I offered my students an introduction to the two opposing ontologies of noted boxers, Muhammad Ali and Jake LoMatta. Joyce Carol Oates (1985) offers that even sports have their own narratives: “Each boxing match is a story, a highly condensed, highly dramatic story--even when nothing much happens: then failure is the story.”

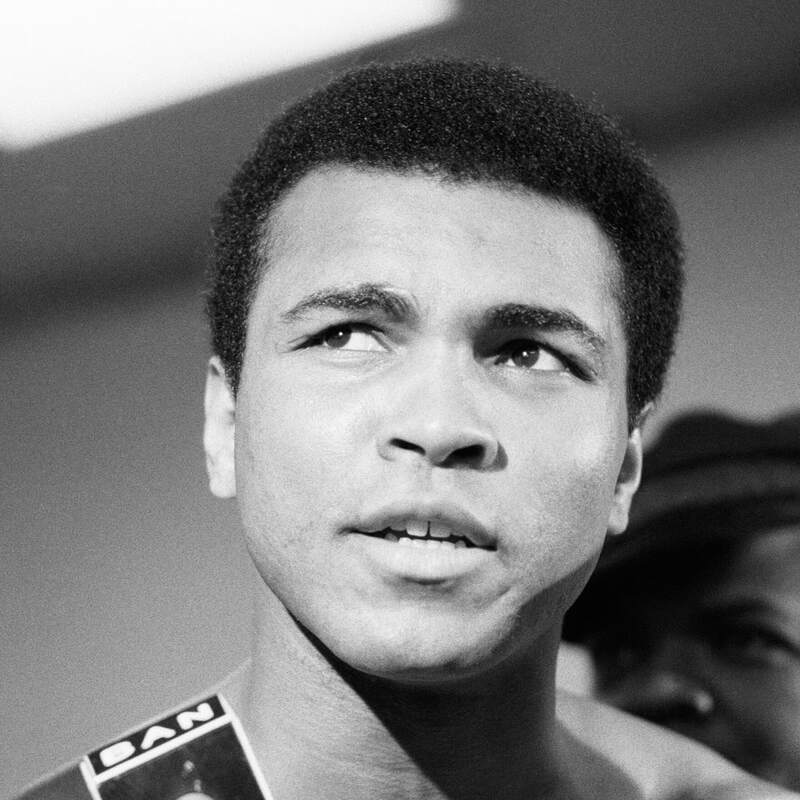

In her book On Boxing, an elaboration of the NYTimes article, Oates highlights the modes and ontologies of several boxers. Two of her descriptions have forever remained in my memory: Muhammad Ali and Jake LaMotta. Each entered matches with a distinct philosophy of the fight, positions suggestive and emblematic of world views. The first, Jake LaMotta entered the ring with the understanding that he would outlast any opponent. As he fought, he became less and less interested in dodging any punch that came his way; instead, he was simply able to endure the throws and jabs of his opponent. He trained for and felt that he could simply outlast his adversary and endure any more pain.

By contrast, Ali was a fighter who predicated his boxing on finesse, on the bob and weave and his capacity to never be hit in the face. Famously he claimed, “My face is so pretty, you don’t see a scar, which proves that I’m the king of the ring by far.” LaMotta accepted the hit took the punishment; in stark contrast, Ali agilely dodged it.

By contrast, I offer other extraordinary talents who, while succeeding, nonetheless, endure either physical or psychic pain to succeed. I think of Hall of Famer Mike Webster of the Pittsburgh Steelers, who was known to endure great hits on the field; or Colin Kapernack, who suffered more psychic offences, and Serena and Venus Williams, who like Kapernack, faced racial battle fatigue in the face of systemic oppression, but unlike him, had to contend with the intersectional oppression of sexism. By offering such examples, teachers invite students to judge the protagonist-athletes in their works as demonstrative of one or both of these modes of existence.

Of course, since novels are predicated on conflict and grief, students may situate their main character with LaMotta ontology. Certainly, the YA classic novel, The Chocolate War features a main character who endures the physical beat down on and off the football field. Yet instructors may easily point to other figures, such as Kareen Abdul Jabar, who seem to skillfully manage the conflict on the court with ease, while suffering the blows of systemic racism off.

Next week, I will focus on ways that teachers can guide discussions which focus both on the sport and the overlay of intersectionality, be it gender, race, or sexuality. Come back for Part Two!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed