Today, my colleague and friend Lesley Roessing adds to a post she wrote a year ago. She suggests, and I agree, that more of need to be better acquainted with the YA verse novel. You really should revisit the older post and then enjoy the new books she adds this time around. Lesley is a frequent contributor to Dr. Bickmore's YA Wednesday. She has too many to list her, but it is well worth your time to browse the contributors 'page.

Perhaps another activity for April would be to introduce your students to a variety of verse novels of the course of the Month.

Verse Novels for National Poetry Month

So what was this magic book that Michael read (actually 304 pages)? The novel was K.A. Holt’s House Arrest, an arresting story in its own right, but one reason Michael felt he was able to read the whole book was that the text on each page was less dense. This is a verse novel. In fact, all the choices for these book clubs were verse novels—those by K.A. Holt and Kwame Alexander. And all the boys read two entire books in the eight weeks, and many read three. I wrote about this group of boys in “30+ MG/YA Verse Novels for National Poetry Month”, but I thought it worthy to repeat for those who had not read last year’s blog as it illustrates the immense power of verse novels.

And verse novels aren’t only appealing to reluctant readers. Verse novels can be more lyrical than prose, and proficient readers are engaged by the words, the spacing—sometimes creatively designed, and are intrigued by the effectiveness of the line breaks which nuance the author’s or narrator’s message. Samuel Taylor Coleridge said, “Prose, the best words; poetry, the best words in the best order.”

Many verse novels are actually multi-formatted novels including an assortment of free verse, rhyming verse, graphics, and prose or are written in a variety of poetic forms, introducing readers to new forms and teachers to new mentor texts for teaching writers.

Below are the 33 verse novels I recommended and reviewed last year.

After the slideshow I share 10 more, in no particular order:

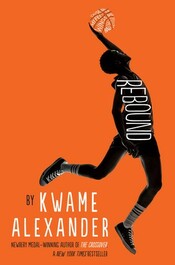

“I want to be the hero in my story.” (339) The year Charlie Bell turned twelve many good things were supposed to happen, but his father died suddenly, and Charlie began to lose his way. His dad was “a star in our neighborhood” but on March 9, 1988, Charlie’s “star exploded.” A good kid, with his best friend Skinny, he starts making bad decisions—skipping school, taking part in stealing an elderly neighbor’s deposit bottles. Even his smart friend CJ, a girl who might become more than a friend, can’t keep him on track. And his life began to revolve around his comics.

Then his mother sends Charlie to spend the summer with his grandparents on their “farm.” Through his grandmother’s love and his grandfather’s work ethic, and most of all, through his cousin Roxie’s obsession with basketball, the re-named Chuck discovers a love for basketball, and he learns to “rebound on the court. And off.” (2)

I became immediately caught up in the rhythm and rhyme of the free verse, and font size, style, and spacing were effectively employed throughout the narrative. However there were a lot of pages devoted to couplet dialogue that broke the rhythm and became somewhat monotonous. Many readers will be engaged by the graphics, comic book style, that are scattered throughout. One disappointment was many erroneous cultural references, pointed out by those reviewers more in tuned with the 80’s than I.

However, I fell in love with Charlie/Chuck and all the other characters, especially granddaddy Percival Bell and cousin Roxie Bell. In fact, I would love to see a novel featuring the young Miss Bell herself. This was definitely a character-driven novel.

A prequel to the popular verse novel The Crossover—Charlie is the twins father—this book would serve as a companion reading but can stand on its own, although I am not sure that the last section, set in 2018, would make sense to those who had not read The Crossover.

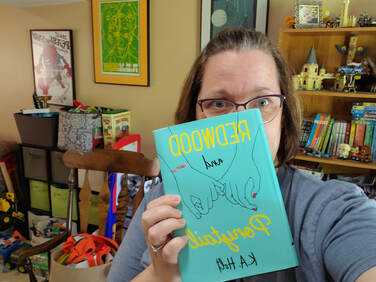

I love all the KA Holt’s novels I have read; Timothy from House Arrest is one of my favorite characters ever. I even have a place in my heart for Rhyme Schemer’s troublemaker-poet Kevin, and I was happy when Levi (House Arrest) grew into his own novel, Knockout (all verse novels) and makes an appearance in this new novel.

Tam (Redwood) and Kate (Ponytail) come from two different worlds.

Kate’s mom puts helicopter parents to shame. She has orchestrated Kate’s entire life so that in 7th grade she will become cheer captain and she will follow her mother’s life—unlike her much older sister who joined the Navy at 18. She lives in the perfect house, which is always being perfected, and her daughter certainly isn’t gay.

Tam’s mother is the opposite. Open and accepting and prone to trying out the adolescent lingo (and providing many of the laughs in reading this book). Tam is also looked after by neighbor Frankie and her wife. Frankie, it appears, is full of advice, based on experience trying to fit the stereotype. Tam is an athlete, tall as a redwood, ace volleyball player, who everyone high-five’s in the hallway, but she realizes she only has one good friend, Levy.

On the first day of school, Tam and Kate meet and, as they quickly, mysteriously, develop deep feelings for each other, they find each not only different from the stereotypes everyone assumes, but, opposite though they seem, opposite though their lives and families may be they each discover they may be a little different than they thought they were and more alike than they thought. Does Kate actually want to be cheer captain or would she rather run free in the team’s mascot’s costume? Does she really want to have lunch at her same old table or would she rather sit with Tam and Levy which is much more fun? Does Tam really want to beat Kate for the school presidency? Or is she punishing Kate for not being able to admit what their friendship may be? As their relationship experiences ups and downs, and they each try to define their attraction, they also find that others may not be as critical and narrow-minded as they assumed.

Written in my favorite format, free verse with some rhymes thrown in for rhythm, the author takes the form to another level with parallel lines and two-voice poetry. I would suggest that the reader have some experience with verse novels before reading. I also loved the Greek chorus—Alex, Alyx, Alexx—who comment on the action and keeps it moving along.

A few years after I graduated from college, I was talking to a friend who had become a social worker. I asked her about her job. “The hardest thing is to have to take a child from his parents,” she said. “No matter how neglectful or abusive the parents are, children don’t want to leave their family or have family members leave them.”

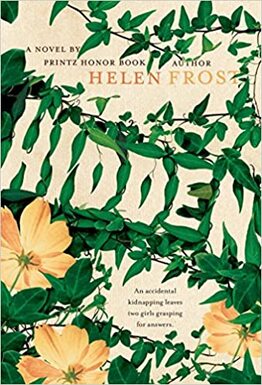

Confusing feelings, complex relationships, and speculative blame develop from a simple plot in Hidden—even though both girls were there.

When she was eight, a man ran from a botched burglary and stole Wren’s mother’s car. Wren was in the back, hidden. West didn’t know she was there until he hid the car in his garage and Heard on the news that a child who was in a stolen car was missing, West’s wife and daughter, although threatened and hit by West, try to find her, and eight-year old Darra leaves food in the garage just in case the girl is there. Wren escapes, and West is caught and sentenced to a jail term, and Darra grows up with ambivalent feelings for the girl who took her “Dad” away.

Six years later the two girls meet at camp. They aren’t sure how they feel about each other, but they agree to avoid each other and not discuss the incident. Until one day they are placed together for a life-saving class event and finally realize that they are the only ones that can discuss the past, and they begin to listen to each other’s side of the story “and put the pieces into place” (124). Darra reflects, “Does she think you can’t love a dad who yells at you and even hits you?”(120). When Wren reveals that she wasn’t the one who turned West in, Darra thinks, “Everything is turning upside down.” And reassures Wren “None of what happened was your fault” (124). Together, they become “stronger than we knew.” (138)

Hidden is written in different styles of free verse. Wren recount her past and present stories in the more traditional style of short lines and meaningful line breaks in combination with meaning word and line spacing. Darra’s narration is crafted in a unique style of long lines and shorter lines, the words at the end of each long line, read vertically, tell Darra’s past memories of her father and explain her love for him. I am glad I happened to read the author’s “Notes on Form” at the end of the story that explained the format or I would have missed the effectiveness of this creative format, although the reader could return to the text for the message.

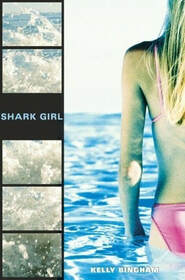

This multi-formatted novel— newspaper clippings, phone conversations, letters, internal dialogue, and mostly free verse—chronicles 15-year-old Jane Arrowood’s life during the year following a shark attack, an attack that took her right arm.

“Where can I find that line to stand upon,

step into the stream of humanity,

the place that is mine.” (112)

A high school junior, Jane has won the art contests every year and planned to become a professional artist. Little did she know when she went to the beach that day, her life and her aspirations would dramatically change. The novel, although fiction, has the feeling of a true story of an actual person. The reader experiences Jane’s ordeal from her perspective, even when she argues with her negative inner thoughts.

Through most of that year, Jane journeys through numerous emotions, the majority negative and despairing. She feels the tingling, throbbing, ache of the phantom limb and the frustration of using a prosthesis. She is not encouraged by the cards and presents sent by strangers—Pity Bears—a result of the video of the attack that someone posted. “Those people who write to me. They tell me they love me. / They don’t even know me.” (71)

Her therapist tells Jane that is natural to be depressed. “Allow yourself to feel as bad as you want. / The sooner you do this, / the sooner you will be able to move on.” (25) and then moves her beyond, a step at a time. “’Time to think about the smaller picture,’ / Mel says. ‘Like getting through one day. / Not your whole life, not forever / one day. / Sometimes we can only look at one hour / or one minute.’”

However, she is supported by family (particularly her brother who rescued her and whose quick-thinking saved her life) and friends, and Jane is greatly inspired by Justin, a little boy who lost both legs but retains his optimism.

In the fall she goes back to school, facing the hurdles of being the Shark Girl, some days bad but some good, support coming from unexpected places and people. “’We’re all just trying to help.’ / [Angie] shifts. ‘I don’t want to see you get hurt again.’” (264)

Although she struggles to train herself to draw with her left hand, Jane begins to reflect on the encouragement she received from hospital staff members (and on those who were unsupportive and unfriendly), and she realizes the difference a person can make. She begins to look into careers in the medical field—physical therapist, art therapist, nurse, doctor, gaining a new goal and purpose. “I’m going to start living again, / only differently.” (265)

This story is truly a mirror and a window that will develop empathy for those who have to navigate life “differently.”

I have written before that I find the most effective way to share and discuss any historical event, and the nuances and effects of those events, is through novels—the power of story. I credit what knowledge and understandings I have of the history and people of Cuba to Margarita Engle’s many verse novels and her first memoir Enchanted Air; reading this memoir was the first time I understood the Cuban Missile Crisis.

I read Engle’s new memoir, a continuation of Enchanted Air, which covers the years 1966-1973. This was more reminiscing, than learning, about the lifestyle and events. As a reader of about the same age of young adult Margarita and possibly crossing paths at some point, I am quite familiar with that time period.

Engle depicts a feeling of duality as she longs for Cuba, home of her “invisible twin,” now that travel is forbidden for North Americans.

Readers witness firsthand the era of hippies, an unpopular war, draft notices, drugs, and Martin Luther King’s speeches and assassination, riots, Cambodia, picket lines, as they follow 17-year-old bell-bottomed Margarita from her senior year of high school to her first university experience, fascinating college courses, books, unfortunate choices of boyfriends, dropping out, travel, homelessness, homecoming, college, agricultural studies, and finally, love.

At one point young Margarita as a member of a harsh creative writing critique group says, “If I ever scribble again, I’ll keep every treasured word secret.” (31). Thank goodness she didn’t. This beautifully written verse novel shares her story—and a bit of history—through poetry in many formats, including tanka, haiku, concrete, and the power of words.

I have always been fascinated by the Scopes “Monkey” Trial; I think much of America has—whether it be about religion vs science, text book and curricula decisions, the role of law and government in education, William Jennings Bryan vs Clarence Darrow, or Spencer Tracy vs Fredric March (Inherit the Wind).

Most of us know the Who, What, Where, When, and believe we know the Why – but do we? How often do we know the true story of historic events—and the stories behind the story, and the different perspectives on the story. Jen Bryant’s historical novel grants us the chance to observe the events of the Scopes Trial close up and personally.

Through this novel, written in the voices of those who had a ringside seat to this trial, readers secure a ringside seat to the trial, the people who participated in it, and the town that hosted it.

As the reader views the controversy and the trial from the point of view of nine fictitious, diverse characters (plus quotes from the real participants), each character develops more as the story progresses. My favorite are the teenagers of Dayton, Tennessee, because, through meeting those on both sides of the issue and closely observing them and the the trial, it affects them, their relationships, and their futures. Peter and Jimmy Lee, best friends become divided by their beliefs; Marybeth is a young lady who finds strength to stand up to her father’s traditional view of the role of women in society; and my favorite character, Willy Amos, meets Clarence Darrow and dares to believe what he can attempt to achieve. “’Well,’ I pointed out, ‘there ain’t no such thing as a colored lawyer.’”…”Do you plan to let that stop you?” (210)

The novel is powerfully written in multiple formats—free verse in a variety of stanza configurations and spacing decisions, a few rhyming lines here and there, and some prose. And the messages are powerful: Peter Sykes—“Why should a bigger mind need a smaller God.” (11); Marybeth Dodd—“I think some people can look at a thing a lot of different ways at once and they can all be partly right.” (131); and Constable Fraybel—“[Darrow] claims [his witnesses] are anxious to explain the difference between science and religious faith and how they made places in their heart and minds for both.” (143)

An epilogue shares the aftermath and the lasting effects of the trial. Every American History/Social Justice teacher and ELA teacher should have copies of this novel.

Our students can learn more about history from novels than textbooks, and, more importantly, stories help them understand history and its effects on the people involved. Familiar with aviator Charles Lindbergh, I was not as knowledgeable about the 1932 kidnapping of his son and the resulting trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, but the most effective way to learn about it was through the eyes, and words, of seventh-grader Katie Leigh Flynn.

Katie is a resident of Flemington, New Jersey, a town where “nothing ever happens.” (5). Katie’s father left her and her mother years ago, and both Katie and her mother are compassionate about the plight of others. The Great Depression has begun; Katie donates food and clothing for less-fortunate children and, when the hotel’s assistant chef is caught putting food in his pockets, her mother says she will “find him an apron with larger pockets.” Katie supports her best friend Mike who “is not like / the other boys I know…he’s not / stuck-up or loudmouthed or silly” (10) and lives with his father, a drunk.

Katie, nicknamed “Word Girl” by the local newspaper editor, plans to become a reporter and keeps a scrapbook of news clippings and headlines, especially about Colonel Lindbergh and the kidnapping. When the Hauptmann is arrested and the trial comes to the local courthouse, her reporter uncle needs a secretary to take notes, and she takes six weeks off school to help. Thus, readers experience the 1935 trial through Katie.

During the trial, readers meet the Lindbergs; the judge; the defendant; the alcoholic defense lawyer who hasn’t won a case in years; prosecutor Wilentz; Anna Hauptmann who swears her husband was at home with her and their baby that night; a witness (paid by the prosecution); and Walter Winchell and other celebrities who come to town for the trial.

The story reminds us that at this time Hitler is in power and discrimination and his persecution has begun in Europe. But Americans are just as prone to prejudice and discrimination. The German bakery changes its sign to “Good American-Baked Bread and Desserts.” [Katie’s] “Mother shrugs, ‘Everything German is suspicious these days.’” (96) And Hauptmann is a German immigrant.

Prejudice is not limited to Germans. People talk about Katie’s friend Mike. “They say: ‘Kids like Mike / never amount to much.’” (24) He is accused of vandalism but when Katie wants to tell who really was responsible, he tells her,

“I’m a drunkard’s son.

You’re a dancer’s daughter.

Bobby Fenwick is a surgeon’s son.

His mother is on

the School Board,

the Women’s League,

the Hospital Auxiliary,

the Town Council,

If you were Mrs, McTavish,

[who is a member of

the School Board,

the Women’s League,

the Hospital Auxiliary,

the Town Council, (110)]

Who would you believe?” (112)

Truth moves to center stage for Katie (if not for anyone else). Thinking about the conflicting testimonies and absence of evidence, she reflects, “Truth must be … like a lizard that’s too quick to catch and turns a different color to match whatever rock it sits upon.” (126) She is careful to write down every word of testimony. “I say, ‘But when a man’s on trial for his life / isn’t every word important?’” (84)

The search for truth is the heart of Jen Bryant’s novel told in free verse. After her experiences, Katie is disillusioned with the American Justice System and says that “…everything used to lay out so neatly, / everything seemed / pretty clear and straight. / Now all the streets run slantwise / and even the steeples look crooked.” (151)

As in Ringside 1925, the novel ends with an epilogue and a reflection on “reasonable doubt,” media, and “the complexities of human behavior” and will lead to important classroom conversations, not about the trial, but about justice.

An engrossing, insightful story about the effects of the events of September 11, 2001. One reason we read is to understand events we have not experienced and the effect of those events on others who may be like ourselves. After witnessing the fall of the first Twin Towers on 9-11, teenager Kyle finds an adolescent girl, wearing wings, poised on the edge of the Brooklyn Bridge. She is covered in ash and has no memory of who she is. He takes her back to his apartment hoping that his father, who is working at Ground Zero, can discover who she is and what she was doing on the bridge. And how she may be connected to, or have been affected by, the events of 9/11.

The Memory of Things is told in alternating narratives—Kyle's in prose, the girl’s perceptions are conveyed through free verse—the two characters sharing their stories and perspectives, introducing adolescent readers, who were not alive during 9/11, to the uncertainty and immediate, as well as lasting, effects of this tragedy.

A story about identity, family, and pride, this short verse novel was written by award-winning poet and novelist Marilyn Nelson.

Connor Bianchini is an Italian-Irish-American adolescent, of 100% Italian heritage on his close-knit father’s side—or so he thinks. When his grandmother dies, she leaves behind the revelation that Connor’s father’s biological father was an American killed during the war.

The family reacts in different, primarily positive, ways to the news. “’It’s funny to think about identity,” / Dad said. ‘Now I wonder how much of us / we inherit, and how much we create.’” (19) Uncle Father Joe says, “You’re as much a Bianchini as I am” and Aunt Kitty although “shocked,” admits “…but I’m glad to know Mama had a Grand Romance! / Tony, nothing makes you less my brother!” (25) Only Dad’s older son Carlo objects to the family announcement, “His says bad news should be told privately.” (79)

As Connor tries to discover more about his grandfather, nicknamed Ace, he has two clues: a class ring engraved with two initials and the term “Forcean” and a pair of pilot's wings. “Forcean” leads him to the Class of 1939 yearbook of Wilberforce University, an historically black university. Surprised to learn that his grandfather was African-American, “I felt like a helium-filled balloon / only the helium was the word ‘wow.’” (71) Connor’s father has his DNA tested and finds his ancestry is so much more than Irish and Italian. “So Ace connects us to the larger world!” (75) Connor embraces his mixed heritage, “It’s like having more teams you can cheer for! / I’d become a citizen of the world.” And “I walked the [school] halls in slow motion. … Little things I hadn’t noticed before: the subtle put-downs, silent revenges.” (75)

Realizing that this grandfather, a pilot, may have been a Tuskegee Airman, Connor researches and learns as much as he can about the Tuskegee Airmen and welcomes this part of his heredity with openness and pride. He can retain his bond with his family while amplifying his own identity and appreciation of who he is. “Inside I’m both the same and different. / I’m different in ways no one can see.” “I fee there is a blackness beyond skin, / beyond race, beyond outward appearance. / A blackness that has more to do with how / you see than how you’re seen. That craves justice / equally for oneself and for others. / I hope I’ve found some of that in myself.” (117)

A blend of narrative and informational text (the information Connor finds on the Tuskegee Airmen), this is yet another book for learning about people and times in our history, written by the daughter of one of the last Tuskegee Airmen and author of a verse memoir, How I Discovered Poetry.

When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, writer, I think of well-told important stories—whether contemporary or historical, memorable characters, critical messages. When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, person, I think of hugs, compassion, empathy, attention, and action. Now when I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, poet, I will ruminate on the power of words, the rhythm of words, the lyricism of words.

It is hard to believe that Shout is Anderson’s first free-verse writing. I was swept away in the unexpected word choices, startling word combinations, thoughtful line breaks, and subtle alliterations.

[As a child,]

I learned then that words

Had such power

Some must never be spoken

And was thus robbed of both

Tongue and the truth. (16)

In this memoir Anderson generously shares her life—the bottomless depths and the highest peaks—all that made her the force she is today. A challenging family life and the rape that “splits open your core with shrapnel,” clouds of doubt and self-loathing…anxiety, depression, and shame,” leaving “untreated pain / a cancer of the soul / that can kill you.” (69)

But also there were teachers, librarians, and the tutor who taught “the ants swarming across the pages” to form words and meaning, the lessons learned from Greek mythology, the gym teacher who cared enough to inspire her to shape-shift from “a lost stoner dirtbag / to a jock who hung out with exchange students, / wrote poetry for the literary magazine / and had a small group of …friends to sit with at lunch.” (88) and her home in Denmark which “taught me how to speak / again, how to reinterpret darkness and light, / strength and softness…redefine my true north / and start over.” (114)

She describes how the story of her first novel Speak found her and the origin of Melinda, “alone / with her fear / heart open, / unsheltered” (162)

Part Two bears witness to the stories of others, female and male, children, teens, and adults, connected through trauma and Melinda’s story, the questions of boys, confused, having never learned “the rules of intimacy or the law” (181) and the censorship, “the child of fear/ the father of ignorance” which keeps these stories away from them. Anderson raises the call to “sisters of the march” who never got the help they needed and deserved to “stand with us now / let’s be enraged aunties together.” (230)

And in Part Three the story returns to her American birth family, her father talking and “unrolling our family legacies of trauma and / silence.”

Shout is a tale of Truth: the truths that happened, the truths that we tell ourselves, the truths that we tell others, the truths that we live with; Shout is the power of Story—stories to tell and stories to be heard.

Acevedo, Elizabeth. The Poet X. HarperTeen, 2018.

The power of words – to celebrate, to heal, to communicate, to feel.

Fifteen-year-old Xiomara grabbed me immediately with her words. She sets the scene in “Stoop-Sitting”: one block in Harlem, home, church ladies, Spanish, drug dealers, and freedom that ends each day with the entrance of her Mami.

Xiomara feels “unhide-able,” insulted and harassed because of her body. We meet her family—the twin brother whom she loves but can’t stand up for her and a secret that he is hiding; her father who was a victim of temptation, and now stays silent; her mother, taken away from the Dominican Republic and her calling to become a nun and forced into a marriage that was a ticket to America; and Caridad, her best friend—only friend—and conscience,

Bur Xio fills her journal with poetry and when she discovers love, or is it lust, she finds the one person with whom she can share her poetry.

“He is not elegant enough for a sonnet,

too well thought-out for a free write,

Taking too much space in my thoughts

To ever be a haiku.” (107)

Aman gives Xio the confidence to see what she can become, not what she is told she can be, and to appreciate, rather than hide, her body. “And I think of all the things we could be if we were never told out bodies were not built for them.” (188)

She also begins to doubt religion and defy the endless rules her mother has made about boys, dating, and confession. With the urging of her English teacher, Xio joins the Poetry Club and makes a new friend, Isabelle “”That girl’s a storyteller writing a world you’re invited to walk into.” (257) and with the support of Isabelle, Stephan, and Chris “My little words feel important, for just a moment.” (259)

When her mother discovers that Xio has not been attending her confirmation class, things come to a climax; however, even though her obsession with poetry has destroyed relationships in her family, it also, with some “divine intervention,” becomes the vehicle to heal them.

As I read I wanted to hear Xio’s poems, but when I finished the book, I realized that I had. A novel for mature readers, The Poet X features diverse characters and shares six months’ of interweaving relationships built on words.

Lesley has published four professional books for educators: The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension; Comma Quest: The Rules They Followed—The Sentences They Saved; No More “Us” and “Them”: Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect; and Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically and Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core. She contributed chapters to two anthologies, Young Adult Literature in a Digital World: Textual Engagement though Visual Literacy and Queer Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the English Language Arts Curriculum.

Her newest book, Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) features many of these novels, as well as many of those in her 2018 guestblog “30+ MG/YA Verse Novels for National Poetry Month” plus other verse novels in her section on planning book clubs by genre or format and for poetry clubs.

Until next time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed