Sports, Young Adult Literature, and Sociopolitical Issues by Alan Brown, Luke Rodesiler, and Mark Lewis

I love offering the space to share what they are doing. Their introduction below is fantastic. I saw that they cover some of my favorite YA sports novels and introduce me to a few that are now on my "To Be Read List." I hope take a minute to read the post.

| Alan Brown is associate professor of English Education and chair of the Department of Education at Wake Forest University. He can be reached at [email protected]. | Luke Rodesiler is associate professor of secondary education and chair of the Department of Teacher Education at Purdue University Fort Wayne. He can be reached at [email protected]. | Mark Lewis is professor of literacy education at James Madison University. He can be reached at [email protected]. |

| Author and journalist Keith O’Brien (2024) recently wrote an article for The Atlantic titled “You’ll Miss Sports Journalism When It’s Gone.” The premise, as the title suggests, may be clear to the average reader but the connection to young adult literature (YAL) and English language arts perhaps not so much. The byline for the article reads: “The ranks of sports reporters are thinning--making it easier for athletes, owners, and leagues to conceal hard truths from the public.” Hard truths often reflect the sociopolitical issues of our time. These truths impact our students on a daily basis because sports impact our students. Like journalists and editors, English language arts teachers are uniquely positioned to support students as they use various types of texts to question the status quo of their shared humanity. |

| Journalists such as retired New York Times sports reporter and award-winning young adult author Robert Lipsyte, whose work and career we have gotten to know well over the years, once wrote, “Reading about sports—for athletes and nonathletes—is not about parsing games or explicating plays but about approaching the messy stuff of life from the urgency of emotional action” (Lipsyte, 2016, p. xvii). What Lipsyte and other reporters often do so well is ask the important questions: Who, what, when, where, how, and, most importantly, why? |

| With these standards in mind, we set out to follow up on earlier scholarship that connects sports and literacy, including a previously published edited book from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) titled Developing Contemporary Literacies through Sports: A Guide for the English Classroom (Brown & Rodesiler, 2016), with a text focused exclusively on recommended and award-winning YAL. |

| Our latest book, Reading the World through Sports and Young Adult Literature: Resources for the English Classroom (Rodesiler et al., 2024), includes stories featuring youth athletes—protagonists who are entangled not only in athletic competition but in the complications of life beyond the arena. In writing this book, we sought to provide teachers with a resource that features rationales for studying YAL, sports culture, and sociopolitical issues in secondary school settings; information about works of contemporary sports-related YAL that can anchor distinct units of study; instructional methods teachers can use to engage students at each stage of reading; and ideas about other sports-related texts—contemporary, canonical, nonfiction, and nonprint—that can be used to supplement instruction, whether through book clubs or film study. |

- A Season of Daring Greatly by Ellen Emerson White (Combating Sexism and Misogyny in Sports Culture)

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely (Protesting Systemic Racism in Schools and Society)

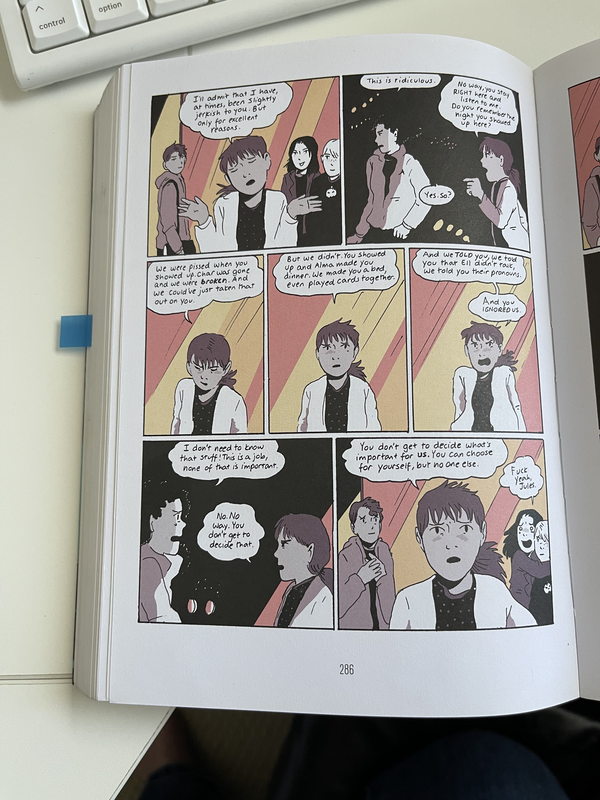

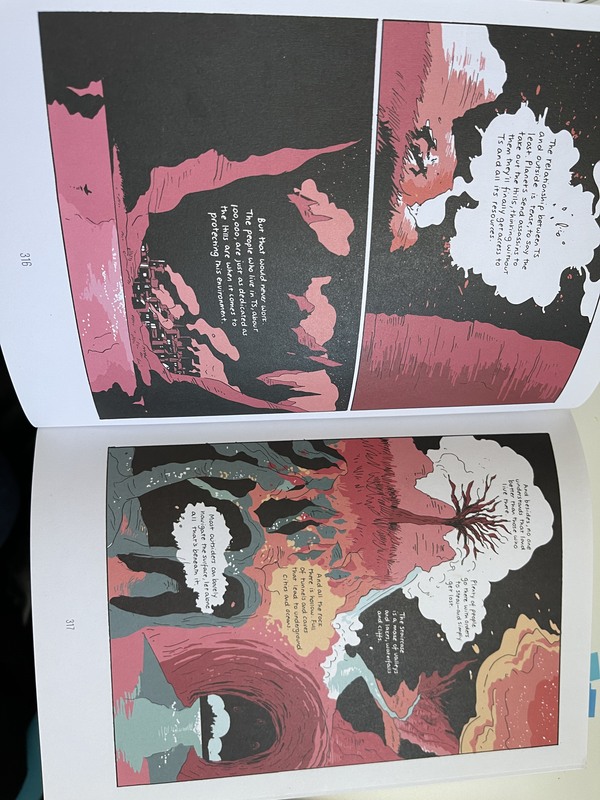

- Spinning by Tillie Walden (Challenging Homophobia in Sports and Society)

- The Running Dream by Wendelin Van Draanen (Upending Ableist Perspectives in the Arena and in Life)

- Hit Count by Chris Lynch (Confronting the Dangers of Contact Sports Head On)

- Exit, Pursued by a Bear by E. K. Johnston (Interrogating the Intersections of Sports and Sexual Violence)

- The Boxer by Reinhard Kleist (Grappling with Death and Dying through Sports)

- Here to Stay by Sara Farizan (Disrupting Bullying Behaviors in Schools, in Sports, and in Society)

- The New David Espinoza by Fred Aceves (Questioning Messages about Masculinity in Sports and Other Popular Cultures)

- Heroine by Mindy McGinnis (Reckoning with Drug Abuse among Athletes and Everyday People)

Brown, A., & Crowe, C. (Eds.). (2014). From the guest editors. English Journal, 104(1), 11-12.

Brown, A., & Rodesiler, L. (Eds.). (2016). Developing contemporary literacies through sports: A guide for the English classroom. National Council of Teachers of English.

Lipsyte, R. (2016). Foreword: Sports culture. In A. Brown & L. Rodesiler (Eds.), Developing contemporary literacies through sports: A guide for the English classroom (pp. xv-xvii). National Council of Teachers of English.

National Council of Teachers of English / International Reading Association. (2012). Standards for the English Language Arts. https://ncte.org/resources/standards/ncte-ira-standards-for-the-english-language-arts/

O’Brien, K. (2024, February 6). You’ll miss sports journalism when it’s gone. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/02/sports-illustrated-journalism-pete-rose/677351/

Rodesiler, L., Lewis, M. A., & Brown, A. (2024). Reading the world through sports and young adult literature: Resources for the English classroom. National Council of Teachers of English.

Aceves, F. (2020). The new David Espinoza. HarperTeen.

Farizan, S. (2018). Here to stay. Algonquin.

Johnston, E. K. (2016). Exit, pursued by a bear. Dutton.

Kleist, R. (2014). The boxer: The true story of holocaust survivor Harry Haft. SelfMadeHero.

Lynch, C. (2015). Hit count. Algonquin.

McGinnis, M. (2019). Heroine. Katherine Tegen/HarperCollins.

Reynolds, J., & Kiely, B. (2015). All American boys. Caitlyn Dlouhy/Atheneum.

Van Draanen, W. (2011). The running dream. Alfred A. Knopf.

Walden, T. (2017). Spinning. First Second.

White, E. E. (2017). A season of daring greatly. Greenwillow.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed